Digital Journal for Philology

»Siddhartha«, the Paradox, and the Counterculture

While Hermann Hesse’s work was read widely before the 60s, the Counterculture’s fixation on his work led to a parallel scholarly fixation on its global reception and impact. It is as if the then immensely popular public response to Hesse’s work, the scholarship that dealt with its global reception and the subsequent institutionalization thereof,1 were orchestrated to amplify Hans Robert Jauß’s contemporary ideas on reception theory. Jauß’s reception theory is a useful tool for understanding how one text can inspire myriad lines of thought, inquiry, and response. It is a theory that liberates a text from being studied only according to the contexts of its first publication. I therefore seek to discover why, about 45 years after its first publication, Siddhartha was so important for the U.S. Counterculture. But unlike much of Hesse-scholarship influenced by reception theory, I do not intend to anchor Siddhartha to the historical moment of U.S. Counterculture. While I first argue that Siddhartha’s paradoxical philosophy complements the paradoxical tenets of the U.S. Counterculture that had adopted it as a manifesto, at the end of this paper, I build off of my findings to examine the nomenclature of a contemporary political and social movement, namely Occupy.

Revisiting Reception Theory

In 1967 at the University of Konstanz, Jauß gave his inaugural lecture on recalibrating literary history according to processes of reception: »Literaturgeschichte als Provokation der Literaturwissenschaft« / »Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory«.2 His argument here is to expand literary analysis beyond the narrow historical moment of textual production in favor of engaging the inclusive present of textual reproduction: a text lives uncountable lives, unfathomable incarnations, most of which surpass the life breathed into it by its so-called original author and first set of readers and critics. Jauß intends neither to extract a text from its historical emergence nor to immerse it in a contemporary moment. According to Jauß, for the future of literary analysis, a text should be seen as a continual, non-linear, non-singular evolutionary event with respect to its socially formative function. A text thereby takes into account both its position in a particular, narrow, historical context as well as its talismanic merit with an unknowable potential for personal and social restructuring. In so doing, Jauß brings the reader—actually readers—into focus. The audience no longer occupies a passive role. Readers are active participants who duly challenge »the prejudices of historical objectivism« and help replace »the traditional approach to literature […with] an aesthetics of reception and impact«.3 He writes, famously:

In the triangle of author, work and reading public the latter is no passive part, no chain of mere reactions, but even history-making energy. The historical life of a literary work is unthinkable without the active participation of its audience. For it is only the through the process of its communication that the work reaches the changing horizon of experience in a continuity in which the continual change occurs from simple reception to critical understanding, from passive to active reception, from recognized aesthetic norms to a new production which surpasses them.4

Im Dreieck von Autor, Werk und Publikum ist das letztere nicht nur der passive Teil, keine Kette bloßer Reaktionen, sondern selbst wieder eine geschichtsbildende Energie. Das geschichtliche Leben des literarischen Werks ist ohne den aktiven Anteil seines Adressaten nicht denkbar. Denn erst durch seine Vermittlung tritt das Werk in den sich wandelnden Erfahrungshorizont einer Kontinuität, in der sich die ständige Umsetzung von einfacher Aufnahme in kritisches Verstehen, von passiver in aktive Rezeption, von anerkannten ästhetischen Normen in neue, sie übersteigende Produktion vollzieht.5

Worldwide, scholars heeded this call to advance the study of literature through the examination of a current reading public; the immense and rather sudden global popularity of Hesse’s work in the 60s coincidentally served as a prime model for Jauß’s enterprise. Many scholars, especially in the United States, began to look at Hesse’s work primarily in terms of its Counterculture reception.

But soon enough, some scholars got stuck once again in the very stagnant tradition of scholarship that Jauß was trying to rattle, stuck in a new historical moment, wherein Hesse’s work became inextricable from, even synonymous with, the Counterculture. As Jefford Vahlbusch points out, U.S. scholarship on Hesse’s work became so drearily monotonous that the eminent Hesse scholar Theodore Ziolkowski lambasted this fixation on reception, pointing obsoletely at Jauß’s reception theory and ironically at his own scholarship. At the 1977 international symposium in Marbach am Neckar that marked the centennial of Hesse’s birth, Ziolkowski, himself the author of numerous articles on the Hesse-reception—such as »Saint Hesse among the Hippies« (1969); »Hesse’s Sudden Popularity with Today’s Students« (1970); »Hesse and Film: the Seduction of a Generation« (1973); and »The Hesse Phenomenon« (1975)—»declared that ›the astonishing Hesse trend in the USA‹ had been nattered to death‹ (›zu Tode geschwatzt‹) and ›analyzed ad nauseum‹«.6 Moreover, this fixation entrenched some critics of Hesse, like George Steiner, in their discredit of Hesse’s literary merit; if Hesse’s work could receive such widespread, popular support—as proven by scholars who intended to show its influence on a generation of hippies, beatniks and radicals—it must lack the subtlety of expression required for critical works of literature deserving of scholarly attention. Although referring here to Hesse scholarship in German-speaking Europe, Ingo Cornils’s acclaim of recent scholarship written on Hesse’s work shows us how the same texts that garnered mass appeal and scholarly derision can inspire new, commendable studies in new settings:

The view that Hesse is somehow not worthy of ›serious‹ literary engagement is rapidly changing, as a new critical edition of his works, a reevaluation of his political thought in the context of global environmental developments, and an appreciation of his seemingly simple yet profound message give rise to research around the world. […] [H]is writings are eminently suited to literary study: they offer moments of sublime beauty and important clues for the understanding of the human psyche.7

While Jauß’s work is by no means infallible, it is anything but obsolete—its merit lies in its insistence on innovation, especially that scholarship not dismiss the reader’s history as part of a legitimate critical encounter with a text. In some sense, Jauß is calling for a quasi-postmodern reading of literature, one that engages a text in its evolving historical, possibly communal context as well as through its current, possibly expressly individual context. He writes, »A literary work is not an object which […] offers the same face to each reader in each period. […] A literary work must be understood as creating a dialogue, and philological scholarship has to be founded on a continuous re-reading of texts, not on mere facts«8 / »Das literarische Werk ist kein für sich bestehendes Objekt, das jedem Betrachter zu jeder Zeit den gleichen Anblick darbietet. [...] Dieser dialogische Charakter des literarischen Werkes begründet auch, warum das philologische Wissen nur in der fortwährenden Konfrontation mit dem Text bestehen kann und nicht zum Wissen von Fakten gerinnen darf«.9

The implementation of reception theory stagnates with the establishment of a conglomerate reading public devoid of nuance, when Hesse’s (or any) work presumably offers the same face to each reader in a particular period.

In the remainder of this paper, I tacitly wrestle with the major problem of reception theory: to build a theory based on reception requires generalizations about readership that efface the very individual recipient of a text that this theory is meant to liberate. By focusing on the Counterculture’s relationship to Hesse’s Siddhartha, I argue for the possibility to refer to the Counterculture as both a common reading public and as an unsystematic collection of individualists. In other words, I argue that the Counterculture’s relationship to Siddhartha gives us a way to understand an intriguing paradox of the Counterculture, how this movement has been treated en masse even though it is made of »many different people doing many different things«.10 First, however, in order to understand the role Siddhartha played for the Counterculture, I highlight this text’s tension-filled quality, manifest in its palpable use of the paradox. In an interpretive move, I illuminate the paradoxical »teachings« and paradoxical language of Siddhartha to demonstrate why this text, as it consistently refutes what it espouses, complemented the Counterculture.

The Paradox of Siddhartha’s Teachings and the Paradox of Counterculture

From Hesse’s Siddhartha:

There is in fact—and this I believe—no such thing as what we call »learning«. There is, my friend, only knowing, and this is everywhere; it is Atman, it is in me and in you and in every creature. And so I am beginning to believe that this knowing has no worse enemy than the desire to know, than learning itself.11

Es gibt so, so glaube ich, in der Tat jenes Ding nicht, das wir »Lernen« nennen. Es gibt, o mein Freund, nur ein Wissen, das ist überall, das ist Atman, das ist in mir und in dir und in jedem Wesen. Und so beginne ich zu glauben: dies Wissen hat keinen ärgeren Feind als das Wissenwollen, als das Lernen.12

The paradox of the Counterculture movement, as it were, is in these lines as they traverse the historical moment. This quote from Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha carries a message: the bane of knowledge is the desire for it, that desire which is here and often elsewhere synonymized with learning. Siddhartha is a story that follows the trajectory of a boy reaching the limits of learning, the limits of knowledge-seeking, along its manifold paths. Some paths he treads longer than others, and each is rejected by or rejects him: scholarship, religion, philosophy, business, love, family and asceticism. Some renowned scholarship appropriately assesses this rejection as a critique of these various facets of culture, but all too often this scholarship ignores the rejection/critique of learned spiritualism, too. It is not just the State that is being contended with in Hesse’s stories, but everything that requires education. In defining »the American Youth Movement« and its protest against the State, Egon Schwarz once argued the sameness of Hesse’s so-called »grievances« and those of the »American radicals«:

[…] another, perhaps the real, target of Hesse’s attacks: the state and ultimately any authority except the spiritual authorities freely chosen by the individual himself. The state comes in for unrelenting criticism. Modern industrialism is assailed in all its aspects: capitalism, nationalism, institutionalized religion, militarism, war, every manifestation of bourgeois aggressiveness are unremittingly rejected.13

Schwarz draws a parallel between themes in Hesse’s work and the resistance to authority to which he must have borne witness during the turbulent political events of the 60s. For Schwarz, the American Youth Movement drew out and highlighted these themes in Hesse’s work. What I find puzzling in Schwarz’s analysis is his circumvention of the critique of the spiritual: »the spiritual authorities freely chosen by the individual«, according to Schwarz, do not come under attack in Hesse’s work. But in Siddhartha, even lessons in spirituality, including the freely chosen ones, are put to question.

For instance, the »Atman« that Siddhartha explains as the only knowledge—in essence, the spiritual experience of the self—cannot be taught, learned or transmitted. While Siddhartha admits at times to have been taught, he also insists that what he has been taught is of no special value. Toward the end of the story, Siddhartha tells his old friend Govinda that what he had learned from the Buddha, for example, is no more or less special than what he is currently learning from the rock next to him. In matters of spirituality as in matters of the State, one can be taught how to know by anyone or anything, that is, one can learn from anyone or anything, but such learning does not impart knowledge. Moreover, if one nonetheless feels knowledge gained, wisdom will remain elusive.

»I have had thoughts, yes, and insights, now and again. Sometimes, for an hour or a day, I have felt knowledge within me, just as one feel’s life within one’s heart. There were several thoughts, but it would be difficult for me to hand them on to you. You see, my Govinda, here is one of the thoughts I have found: Wisdom cannot be passed on. Wisdom that a wise man attempts to pass on always sounds like foolishness«.

»Do you speak in jest?« Govinda asked.

»It is no jest. I am saying what I have found. One can pass on knowledge but not wisdom. One can find wisdom, one can live it, one can be supported by it, one can work wonders with it, but one cannot speak it or teach it«.14

»Ich habe Gedanken gehabt, ja, und Erkenntnisse, je und je. Ich habe manchmal, für eine Stunde oder für einen Tag, Wissen in mir gefühlt, so wie man Leben in seinem Herzen fühlt. Manche Gedanken waren es, aber schwer wäre es für mich, sie dir mitzuteilen. Sieh, mein Govinda, dies ist einer meiner Gedanken, die ich gefunden habe: Weisheit ist nicht mitteilbar. Weisheit, welche ein Weiser mitzuteilen versucht, klingt immer wie Narrheit«.

»Scherzest du?« fragte Govinda.

»Ich scherze nicht. Ich sage, was ich gefunden habe. Wissen kann man mitteilen, Weisheit aber nicht. Man kann sie finden, man kann sie leben, man kann von ihr getragen werden, man kann mit ihr Wunder tun, aber sagen und lehren kann man sie nicht«.15

At this late stage of the story, after Siddhartha has already repudiated at length the possibility of transferring knowledge, it may seem contradictory that he flippantly speaks of knowledge as transferable and so distinct from wisdom. This very flippancy, however, is significant because it demonstrates Siddhartha’s distrust of words and his customary conflation of knowledge, wisdom and spiritual enlightenment. The focus, here, is thus on the impossible process of transfer from one to another of that which occurs through self-discovery and personal experience. This is the acclaim of the highly individualistic path. In sum, but in no simple way, this text asserts a rejection of learning—of guidance, of teaching and of being taught, and of training—in all its aspects and for all its goals, including knowledge, wisdom, and spiritual enlightenment.

However, is not this assertion—of the rejection of learning—a lesson? Does not Siddhartha teach individualism? Considering the historical moment of the Counterculture, this text, this »indische Dichtung«, which rejects learning, became itself a guide to a movement. Often regarded as a Bildungsroman, if this text not only rejects Bildung, but rejects itself, as Roman, should not Siddhartha, too, have been rejected by the Counterculture?

If the first paradox occurs within the text (the paradox of learning knowledge or gaining wisdom), a second paradox crystallizes when the very individualism that this text paradoxically teaches helps band its readers together into a movement. Siddhartha became known as a Bible of the Counterculture,16 hailed as holier than the New Testament.17 Narrated in deceptively simple, hypnotic prose, this story called many of its readers to follow Siddhartha’s path, invited them to transform into devotees. As the Buddha’s namesake, the title of the story alone suggests such an invitation. But Siddhartha is far more involute. In fact, it does not invite followers; it sends them away, as in the case of Siddhartha’s childhood friend Govinda intent on following Siddhartha’s brazen footsteps. The name »Siddhartha«, which translated from the Sanskrit means »one who has achieved the goal«, in the context of this story tells us that Siddhartha has already and always reached his goal, that the trials he faces are not lessons in any teleological sense, but are a mere unfolding of his own knowledge which is always present. This Siddhartha comes in stark contrast to the other »historical« Siddhartha Gautama—the Buddha (who does make an appearance in this story)—who was a sage and who set out to teach the Middle Path to liberation. Despite the individualistic nature of the path taken by Siddhartha in Hesse’s story, this path became a model to emulate not unlike the Buddha’s.18 Siddhartha’s path awakened a craving for spiritual enlightenment that could be satiated through the teachings of individualism. As Siddhartha’s Eigensinn, or self-will, taught its followers how to chart an obstinate, revolutionary path against authority, it also, in effect, took a paradoxical collective turn.

It was Timothy Leary and Ralph Metzner’s praise of »Hermann Hesse: Poet of the Interior Journey« in The Psychedelic Review that sped up Hesse’s rise to fame in the United States. In their review of Hesse’s work, which includes an analysis of Siddhartha, they help give the emphatically individualized self-will espoused in Hesse’s work a paradoxical sense of community. They claim that »[m]ost readers miss the message of Hesse. Entranced by the pretty dance of plot and theme, they overlook the seed message. […] the seed, the electrical message, the code is in the core«.19 Dutifully, Leary and Metzner do not reveal the core, do not unpack the seed, but recapitulate scenes from Hesse’s stories to inform of the seed’s existence. It is impossible to unpack the seed for one another; such a seed is as distinct as each reader is from the next. But they insist that such a seed exists in Hesse’s work, and that it exists for each reader. They write: »But always—Hesse reminds us—stay close to the internal core. […] The [internal] flame is of course always there, within and without, surrounding us, keeping us alive. Our only task is to keep tuned in«.20 In their highly spiritual, laudatory, and psychedelic rendering of Siddhartha, Leary and Metzner descriptively engage the ineffable nature of the internal core, thereby establishing a core for each reader, though they do not have access to the nature of each core. Each reader of Hesse has access only to his/her own core, which lies at the nexus of Hesse’s text and the reader. In their essay, Leary and Metzner establish a kind of spiritual collective experience of reading Hesse, crafting camaraderie among the radically individual. While each path of reading Hesse is distinct, each with a distinct reader and distinct core, their collective experience is built upon their readership: individuals reading Hesse together, seeking an internal core together. Readers of Hesse are at once free to discover themselves and the world in whichever ways they see fit (in ways that often challenge authority… which may or may not include psychedelic drugs and pilgrimages to India) and find solace in belonging to a group of Eigensinnigen, more commonly known as the Counterculture.

The Paradox of Language

With regard to the »seed message« of Siddhartha, Leary and Metzner infer that we can think of a seed, we can reference a seed, be guided to a seed, but cannot know a seed through language, even though through language we learn about the seed. They thereby pick up on the rift between learning and knowledge prevalent in Siddhartha. In so doing, they point in particular to the role of language in shaping this rift, for language, the tool used to teach and learn that a seed exists in the first place, cannot be used to know the seed. This tension with the efficacy of language is highlighted in the very last chapter of Siddhartha.

Siddhartha consistently refutes the very teachings it espouses; it rails against any form of learning. In the last chapter, Govinda implores Siddhartha to share his path with him, so that Govinda, too, may traverse the path to spiritual enlightenment as Siddhartha seemingly has. Siddhartha, however, warns Govinda that no teaching is teachable, resting his case on the inefficacies of language. Siddhartha even warns against his own attempts at teaching language’s failures, because language is required to do so. When Siddhartha explains that language breaks the world into oppositional frameworks, he is, in a way, speaking with a Heideggerian vocabulary: as language discloses something, it conceals something else. Language can never reveal the whole picture. Siddhartha tells Govinda:

Everything is one-sided that can be thought in thoughts and said with words, everything one-sided, everything half, everything is lacking wholeness, roundness, oneness. When the sublime Gautama spoke of the world in his doctrine, he had to divide it into Sansara and Nirvana, into illusion and truth, into suffering and redemption. This is the only way to go about it; there is no other way for a person who would teach.21

Einseitig ist alles, was mit Gedanken gedacht und mit Worten gesagt werden kann, alles einseitig, alles halb, alles entbehrt der Ganzheit, des Runden, der Einheit. Wenn der erhabene Gotama lehrend von der Welt sprach, so musste er sie teilen in Sansara und Nirwana, in Täuschung und Wahrheit, in Leid und Erlösung. Man kann nicht anders, es gibt keinen andern Weg für den, der lehren will.22

Siddhartha’s explanation of language’s failure is at once the exoneration thereof. There is no way other than through language—through some semblance of signs—to teach or tell anyone anything. Language thus becomes the metonym for teaching, which, as with all else, Siddhartha rejects. He uses it nevertheless to communicate with Govinda.

Initially, Govinda has difficulty understanding Siddhartha. Just as Siddhartha had forewarned, Siddhartha’s wisdom sounds to Govinda more like foolishness. But this is the very essence of Siddhartha’s words—that they cannot transmit any wisdom; they are foolish, by virtue of their being told through words:

Words are not good for the secret meaning; everything always becomes a little bit different the moment one speaks it aloud, a bit falsified, a bit foolish—yes, and this too is also very good and pleases me greatly: that one person’s treasure and wisdom always sounds like foolishness to others.23

Die Worte tun dem geheimen Sinn nicht gut, es wird immer alles gleich ein wenig anders, wenn man es ausspricht, ein wenig verfälscht, ein wenig närrisch – ja, und auch das ist sehr gut und gefällt mir sehr, auch damit bin ich sehr einverstanden, dass das, was eines Menschen Schatz und Weisheit ist, dem andern immer wie Narrheit klingt.24

At the very end of this final scene, there is a notable shift in point of view from Siddhartha to Govinda, echoing the very chapter title, »Govinda«. Siddhartha is no longer speaking, but we are witness to Siddhartha through Govinda’s inner conflict. Govinda secretly thinks, as »his heart filled with conflict«:

His doctrine may be strange, his words may sound silly, but his gaze and his hand, his skin and his hair, everything about him radiates a purity, radiates a calm, radiates a gaiety and kindness and holiness that I have beheld in no other person since the final death of our sublime teacher.25

Mag seine Lehre seltsam sein, mögen seine Worte närrisch klingen, sein Blick und seine Hand, seine Haut und sein Haar, alles an ihm strahlt eine Reinheit, strahlt eine Ruhe, strahlt eine Heiterkeit und Milde und Heiligkeit aus, welche ich an keinem anderen Menschen seit dem letzten Tode unseres erhabenen Lehrers gesehen habe.26

Though late in the story and though via the perspective of a supporting character, this experience of an inner conflict is the climax, the major turning point that leads to Siddhartha’s final disappearance into formlessness, likened here to the enlightened state of the Buddha. Govinda begs Siddhartha for just one more word, one more lesson in his search for ultimate knowledge: »Grant me just one word more, O Revered One; give me something that I can grasp, that I can comprehend! Give me something to take with me when we part. My path is often difficult, Siddhartha, often dark«27 / »Sage mir, Verehrter, noch ein Wort, gib mir etwas mit auf meinem Weg. Er ist oft beschwerlich, mein Weg, oft finster, Siddhartha«.28 In response, seeing »eternal not-finding« (»ewiges Nichtfinden«) in Govinda’s eyes, Siddhartha asks Govinda to kiss him on his forehead. »›Bend down to me‹, he whispered softly in Govinda’s ear. ›Bend down here to me! Yes, like that, closer! Even closer! Kiss me on the forehead, Govinda!‹«29 / »›Neige dich zu mir!‹ flüsterte er leise in Govinda’s Ohr. ›Neige dich zu mir her! So, noch näher! Ganz nahe! Küsse mich auf die Stirn, Govinda!‹«30

What follows is remarkable, not merely for the hierophantic description, but for the explicit continued presence of »words« in Govinda’s experience of Siddhartha’s formlessness, of his being without words.

For Govinda, what was before an inner conflict is now a harmonious simultaneity. When Govinda kisses Siddhartha, there is a transfer of knowledge described like no other in the entire story. Considering the motif of the impossibility of teaching knowledge or wisdom, this transfer of knowledge is unorthodox. It is, in fact, less a transfer than a revelation. Using a framework borrowed from Mircea Eliade’s The Sacred and the Profane, knowledge, wisdom and enlightenment had been, through their elusiveness, ineffability and desirability, in many respects consecrated, whereas learning and words belonged to the realm of the profane. In the moment of bowing to and kissing Siddhartha’s forehead, Govinda is witness to hierophany, a manifestation of the sacred.31

At this hierophantic moment, one might expect »words« to retreat into the background or even to vanish altogether, for they have been the very bane of Govinda’s search for (not to mention Siddhartha’s own search for and experience of) knowledge and wisdom. But words remain. The paragraph that introduces Govinda’s experience of Siddhartha’s formlessness shows the necessity of paradox for hierophany. In the hierophantic moment, words are at once meaningless and meaningful because they are no longer just words signaling polemical concepts, indescribable experiences, or impossible objects; words are imbued with cosmic sacrality and signal all at once, simultaneously manifesting that which they reveal and conceal. In this moment of knowledge revelation, words do not disappear, but are integrated into an entirety of experience. There are two important elements in this final scene that underscore the simultaneity of words and knowledge in Govinda’s hierophany: the word, »while« (»während«) and the punctuation mark, »:«.

[While] Govinda, perplexed and yet drawn by great love and foreboding, obeyed his words, bent down close to him, and touched his forehead with his lips, something wondrous happened to him. While his thoughts were still lingering over Siddhartha’s odd words, while he was still fruitlessly and reluctantly attempting to think away time, to imagine Nirvana and Sansara as one, while a certain contempt for his friend’s words was even then battling inside him with tremendous love and reverence, this happened:

He no longer saw the face of his friend Siddhartha; instead he saw other faces, many of them, a long series, a flowing river of faces, by the hundreds, by the thousands, all of them coming and fading away, and yet all of them appearing to be there at once, all of them constantly changing, being renewed, and all of them at the same time Siddhartha […].32

Er sah seines Freundes Siddhartha Gesicht nicht mehr, er sah statt dessen andre Gesichter, viele, eine lange Reihe, einen strömenden Fluß von Gesichtern, von Hunderten, von Tausenden, welche alle kamen und vergingen, und doch alle zugleich dazusein schienen, welche alle sich beständig veränderten und erneuerten, und welche doch alle Siddhartha waren [...].33

The use of »while«/»während« indicates that the words that Siddhartha had told Govinda did not lead to this hierophany, did not teach Govinda how to receive Siddhartha’s knowledge, but were amplified by the experience of Siddhartha’s enlightened state. Siddhartha’s words and teachings were very much awhirl during the hierophany, hence the added use of the colon before the long, richly descriptive plethora of things and ideas that are Siddhartha, all sensed by Govinda. The colon is a sign of equivalence. Immediately after the colon, the description of Siddhartha’s formlessness continues for forty-two lines, traversing the animate and inanimate, feminine and masculine, objects and ideas, times and spaces, verbs and adjectives, animals and gods; this is a description that seeks to surpass dualities through multitudes.

Along the axis of the colon, Siddhartha’s teachings and words that linger with Govinda are equated with the description of Siddhartha’s dissolution. This equivalence does not invalidate Siddhartha’s previous rejection of words and teachings, does not suddenly deem learning and the use of words a suitable path to the discovery of ultimate knowledge. In fact, the equivalence reinforces that rejection because, in this revelatory moment, words do not lead to knowledge, they just exist with it. When used as a way to knowledge, words and teachings are mere obstacles. But in the moment of revelation, in the occurrence of ultimate knowledge, words and teachings are as much a part of ultimate knowledge as anything else; words and teachings become something else, yet remain what they are. This is the paradox of language that Siddhartha had been preaching, which Govinda only now understands through hierophany. Mircea Eliade describes the paradox existent in the hierophany in the following way:

It is impossible to overemphasize the paradox represented by every hierophany, even the most elementary. By manifesting the sacred, any object becomes something else, yet it continues to remain itself, for it continues to participate in its surrounding cosmic milieu. A sacred stone remains a stone; apparently (or, more precisely, from the profane point of view), nothing distinguishes it from all other stones. But for those to whom a stone reveals itself as sacred, its immediate reality is transmuted into a supernatural reality. In other words, for those who have a religious experience all nature is capable of revealing itself as cosmic sacrality. The cosmos in its entirety can become a hierophany.34

We may now be able to assemble an answer to the question posed earlier: If this were treated as a Bildungsroman that not only rejects Bildung, but rejects itself, as Roman, should not Siddhartha, too, have been rejected by the Counterculture? Just as Govinda was consistently drawn to Siddhartha’s words and teachings, despite producing an inner conflict, so too may readers of Siddhartha have been drawn to learning from this story and its disavowal of being able to teach anything, because it produced a conflict. Govinda’s conflict arose through the paradox of understanding Siddhartha as both wise and foolish, and the mounting tension of this conflict opened up access to Govinda’s hierophantic moment, co-inhabited by both the profane and the sacred. Because any reader of this story, unlike Govinda within the story, must ascertain Siddhartha’s formlessness through the descriptive words formed via Govinda’s perspective, the hierophany experienced by Govinda, which is Siddhartha’s enlightenment, is still available to readers only through words. In order to reach Siddhartha’s state of consciousness and/or Govinda’s witnessing thereof, a reader must come to terms with (that is, embrace) the paradox of language, especially with regard to one »seed message« of Siddhartha: words can be used to inform about concepts of enlightenment, wisdom, or ultimate knowledge, but do not give us access to them.

The Nomenclature of Counterculture

To adhere to the term Counterculture is in many respects to embrace the paradoxical. Counterculture readers may not have tossed Siddhartha aside because they may have found therein the vindication of their paradoxical struggle to collectively assert radical individualism. The interrelated paradoxes of Siddhartha’s teachings, of the Counterculture, and of language all come to the fore in the nomenclature of Counterculture. The name of a political or cultural movement, especially one defined by its opposition to a dominant or mainstream culture, is rarely adequate to account for the range of ideologies under its scope. The scope of a movement’s name is far too small, unless we allow such a name to breathe, to change, to represent at times divergent ideas. Through time, a movement’s name may also become stereotyped and emblematic of a few narrow belief systems represented by the most vociferous and sensational. In the case of the term Counterculture, we might think of the hippie, the beatnik, or the bohemian. As these particular groupings became emblematic of the Counterculture, their particular distinguishing features were lost to the umbrella term. Yet the umbrella term—and even the inadequately named groupings encompassed beneath it—persisted.

This lack of distinction was carried forth by the kind of reception theory scholarship that insisted on treating readers en masse. Akin to reader-response theory that enforced a so-called »implied reader« or »educated reader«, this scholarship effaced the very reader it attempted to give voice to, i.e. the individual one. Jefford Vahlbusch writes that »one of the most curious facts in the literature on Hesse’s U.S. reception [is] the confusing failure or refusal to distinguish successfully or usefully between Beat Generation, beatniks, hippies, adolescents, other members of the counter-culture, teenagers and students«.35 Vahlbusch then comments on famed New Yorker writer George Steiner’s 1969 article, »Eastward Ho!«, which is a piece on the Hesse reception in the United States. Vahlbusch draws an analogy between Steiner’s use of a »hippie girl« as the model for all readers of Hesse and the way reception theory scholarship treated »the reader« of Hesse’s work. Vahlbusch writes:

As the hippie girl is for Steiner, so Hesse’s American readers are for nearly all of the scholars and journalists who have written on Hesse in the USA. Steiner does not inquire about her apparently astonishing knowledge of Hesse’s most challenging novel, nor does he record her name. For Steiner, she is beyond history, context, and individual identity. He makes her an archetype for all hippies and—by his extension—for all young American readers of Hesse. Steiner creates his hippie girl as a rhetorical convenience, an »empty vessel« to be filled with such content and meaning as his argument demands.36

But is this failure to identify the individual readers of Hesse, or the individual compasses of the Counterculture, confusing or curious? The coalescence of disparate individuals into one umbrella term is a natural result of any movement, not just one that seeks definition from within but one that is unsurprisingly and uncompromisingly defined from without by those intending to separate themselves from it, and those intending to study it. What Vahlbusch successfully points to is the need to be aware of a movement’s plural composition of movements.

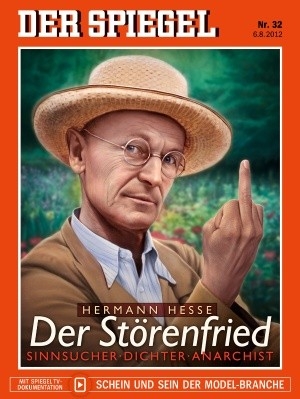

Theodore Roszak, the historian generally credited with coining Counterculture, in the preface to The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflection on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition published in 1969, admits »openly that the much of what is said [in his book] regarding [the] contemporary youth culture is subject to any number of qualifications«.37 According to Roszak, for the sake of saying anything at all about the Counterculture—or any movement which is in fact comprised of »many different people doing many different things«—one must generalize.38 More so than other social movements, late 60s and early 70s Counterculture resisted collective definition because its so-called members championed individualism. The spirit of the times, granted according to a recent article in Der Spiegel on the 50th anniversary of Hesse’s death, could be encapsulated in Siddhartha’s smile from which emanated the notion: »You must find for yourself and yourself alone the way to wisdom. If nothing else, an effective immunization against all ideologies« / »Den Weg zur Weisheit musst du für dich allein herausfinden. Immerhin eine wirksame Impfung gegen alle Ideologien«.39

Figure 1: Title page of Der Spiegel on the 50th anniversary of Hesse’s death

In a few words, the 60s Counterculture was a movement against the mainstream, a rejection of norms, of popularity, of mass media. It was against a culture that promoted homogeneity over heterogeneity. The irony of the Counterculture being given a name, then, lay exactly therein, that its name collectivized the professedly heterogeneous. As the 60s U.S. Counterculture established itself under this moniker, and especially as it was established by those who did not adhere to its tenets, the heterogeneity that this movement sought to promote was restricted by one organizing principle: the movement away from the mainstream. But the movement turned away in innumerable directions. A movement such as the Counterculture was easier defined by what it was against than the new direction it would take. Thus, while the nomenclatural aspect of such a movement can be its binding force, it can also be its undoing.

There are major gains to be had from collectivizing under a name. A movement with a name gains strength and momentum sometimes harnessed for great achievements. But a movement such as the Counterculture, as it gained momentum, also gained an unwieldy, unrepresentative uniformity, especially since it held together a group of radical individualists. When we look back at some of the Counterculture’s most emblematic figures, such as its various musicians and political activists, it becomes absurd to place together those who championed new moral ideals of equality and peace with those who, in a Nietzschean, Dionysian manner rejected all moral codes in favor of self-indulgence. Hesse’s work, in particular Siddhartha, as it gained prominence amongst all kinds of readers, helped forgive Counterculture its nomenclatural inadequacy by highlighting its paradoxical quality. Siddhartha’s paradoxical teachings, especially as Siddhartha discusses the inefficacies of language, helped showcase the paradox as an escape from certainty, where certainty was the symbol of the cultural authorities against which the Counterculture fought. The term Counterculture thus gradually became emblematic of the paradoxes of Siddhartha, such that like the character Siddhartha, whose path traversed both discipline and self-indulgence, the varied adherents of the Counterculture could be idealistic, community oriented, destructive, or self-indulgent.

As a result, the paradoxical term Counterculture afforded its supporters a way to live along the line of tension drawn by the paradox, drawn between the particular and the universal, between the radically individual and the collective. The engagement with its own paradox afforded the Counterculture a kind of unimagined fervor that discovered new ways of being, often as a result of, using Søren Kierkegaard’s terms, passionate collision seeking. Kierkegaard’s description of paradox in Philosophical Fragments (even though in reference to its usefulness for the thinker) helps illustrate why the Counterculture may have thrived, passionately, by fully engaging its paradox. He writes:

[…] one should not think slightingly of the paradoxical; for the paradox is the source of the thinker’s passion, and the thinker without a paradox is like a lover without feeling: a paltry mediocrity. But the highest pitch of every passion is always to will its own downfall; and so it is also the supreme passion of the Reason to seek a collision, though this collision must in one way or another prove its undoing. The supreme paradox of all thought is the attempt to discover something that thought cannot think.40

The Counterculture was, since its conception as such, always on the cusp of its own undoing; it was the attempt to »graft an oak tree upon a wildflower […] such is the project that confronts those […] who are concerned with radical social change«41 This cusp, where the individualistic scraped against the collective, was where the significant revolutions of culture sprouted, including and not limited to the movements for civil rights, women’s rights, racial equality and free speech. This is where particular individual freedoms were ostensibly asserted for the benefit of everyone.

Individualist thinking of the Counterculture was integral to women’s liberation, anti-racist, anti-sexist struggles, where »the goal is to translate antagonism into difference (›peaceful‹ coexistence of sexes, religions, ethnic groups)«.42 The 60s Counterculture was no less a political phenomenon than a social one. As a political phenomenon, the term failed when the movement became popular over time, when it began to fuel the mass media, and especially when it began to espouse its own set of norms. The Counterculture became a new dominant culture to contend with, and the radical individualists that banded together were, perhaps unintentionally, promoting a cause which later movements explicitly drawing upon anti-authoritarian principles of the Counterculture ironically had to counter. In the chapter aptly titled »Obsession for Harmony/Compulsion to Identify« in Demanding the Impossible, Slavoj Žižek alludes to the failure of the Counterculture by pointing out the contemporary consequences of radical individualism:

No wonder large corporations are delighted to accept such evangelical attacks on the state, when the state tries to regulate media mergers, to put strictures on energy companies, to strengthen air pollution regulations, to protect wildlife and limit logging in the national parks, etc. It is the ultimate irony of history that radical individualism serves as the ideological justification of the unconstrained power of what the large majority of individuals experience as a vast anonymous power which, without any democratic public control, regulates their lives.43

Žižek explains that individualist ideals poised to deregulate state power had, in time, backfired, gradually fueling the explosive growth of the super-wealthy and their furtive control over state regulatory practices, which the recent Occupy movement sought to topple as a means to bridge ever-widening economic inequality. In the remainder of this paper, in adherence to my understanding of Jauß’s reception theory, I attempt to contemporize my reading of Siddhartha by building on my findings of Siddhartha’s illustrative paradoxes. I thereby now utilize Žižek’s critique of radical individualism to dramatically shift the focus of this paper from the Counterculture to the contemporary Occupy movement, whose nomenclature is also cause for concern. If rereading Siddhartha helps us think of the Counterculture as many diverse movements, could the Occupy movement also be thought of pluralistically, even if it was arguably born as a reaction against radical individualism and as an attempt to band together not as Eigensinnigen?44

»The Compulsion to Identify«

The Occupy movement and its rallying cry, »We are the ninety-nine percent!« that began in Zucotti Park was »a commitment to fighting the twinned powers of private wealth and public force«.45 What began as a local occupation of a public park in Lower Manhattan spread worldwide, and its temperament was quickly likened to the U.S. Counterculture movement of the 60s. The Occupy movement was different from the Counterculture mainly because it was determinedly against radical individualism, an ideology now represented by the corporate banker. But much like the Counterculture, its nomenclature created problems for the life of the movement. At its start, Occupy Wall Street had a remarkably successful anarchic46 structure, with a horizontal rather than vertical organizational intention: »It inspired similar occupations around the country, creating a model for radical politics in the Obama era. And it became known, more than anything, for its commitment to horizontalism: no parties, no leaders, no demands«.47 But as it grew out of Zucotti Park, its ideals began to take root and become vertical, where the term Occupy stood at the helm of an unwieldy inter- and transnational movement, enabling the occupation of public plazas and government buildings for a wide range of issues, many not directly linked to economic inequality. Certainly, this gesture of occupation is an important show of force for the disenfranchised. But when, especially for more localized struggles, the idea of occupation overrides nuanced methods of affecting change, that very same show of force can draw attention to the disconcerting imperialist rhetoric of »occupation«.

Take, for example, a recent and ongoing »Occupy the Farm« movement in Albany, California intending to prevent the erection of chain supermarkets and other corporate development on some of the last plots of high-grade soil in the Berkeley area. A group of occupiers forced the lock on University of California’s Gill Tract in order to »take back the tract«. They tilled the land and drew up estimable plans to not only turn the tract into an urban farm but also a center for educating the public about food justice issues. But in so doing, the occupiers both inadvertently jeopardized academic research by UC Berkeley plant biologists and alarmed an otherwise supportive neighboring family-housing community with an influx of disruptive strangers. Commotion will accompany any tent city, even the most respectful. It was not the intention of the farm movement to displace UC Berkeley researchers, nor was it their intention to lose support from the neighboring community. The alignment of the relatively small urban farm movement with a movement whose own compass had become dangerously strong silenced more acute, inventive, and subtle forms of resistance with rhetoric of force.

The battle over the plot is still underway. After being evicted by University of California police off the ag-research tract, the occupiers returned to a nearby plot, not ag-land but still officially owned by the University of California. The occupiers were met with staunch resistance by some local community members who have, in their own ways, been fighting for many years to prevent development: »Long before Occupy the Farm, some Gill Tract neighbors had been fighting the proposed development […]«.48 While the occupiers exclaimed their allegiance to the Occupy movement—»We’re tapping into a movement globally to take back land«—the counter-protestors complained of the occupiers’ alignment with this global movement, which had blinded their democratic sense—»They’re not doing it in a democratic way […] They’re being bullies with their rhetoric. It’s like small children throwing their tantrum until they get their way«.49 Using the rhetoric of the global movement (and with it incredible, unwieldy power) for this relatively small movement has turned-off many potential supporters of this cause to rethink land use.

If a movement attends to the resistance from its supporters—in this case reassess the language that drives its tactics—it may actually embolden its stance by acknowledging its shortcomings. In fact, the recent tactical turn of this farm movement involving negotiations with the University and creative protest campaigns to boycott the construction of yet another supermarket has proven to garner a larger network of support.

As Occupy grew in size, it reached many breaking points. It became ever-harder to sustain its participatory democracy and consensus rules, and it especially became ever-harder to sustain one of its early resolutions, non-violence, which had, in many ways, to do with the ideals that accompany occupation and the problems that accompany collectivizing. The purpose of bringing the nomenclature of movements under scrutiny is not to utterly denounce Occupy or Counterculture, but to question the ways in which we feel compelled to negotiate our being, our proclivities, with rhetoric that inevitably fails; that to get behind something means, to some degree, to forgo subtlety of individual expression. A movement is taken as a movement because it has some guiding principle, some moral compass, some phrase or term to point to the way things ought to be organized, consequently requiring some individual compromise. In the case of the Counterculture, then, a movement heavily dependent on securing individualistic ideals, in order to rescue the significance of the individual from the unwieldy uniformity of the group, Counterculture might need an updated definition. Taking cues from deconstructive criticism helps in this process.

[…] why use language at all if it seems to refer to a kind of stable meaning that doesn’t really exist? We must use language, Derrida explains, because we must use the tool at our disposal if we don’t have another. But even while we use this tool, we can be aware that it doesn’t have the solidity and stability we have assumed it has, and we can therefore improvise with it, stretch it to fit new modes of thinking […].50

Analogously, if »Counterculture« is the tool at our disposal, a term ossified by history, then it may be time to improvise with it in order to better signal the innumerable ideas, ideals and ideologies under its scope. If we understand »counter« not only as a term signaling opposition in the sense of »against« or »contrary to« a mainstream culture, but also as a term that qualifies the culture of this movement of radical individualist, then we may be able to understand »counter« in terms of »counting«. In other words, we ought to think of the Counterculture as a movement that tallied its every member, that sought to make its every member count.

Conclusion

Movements hold onto names, even if inadequate, because the tension-filled paradox between individual and collective will that nomenclature engenders delineates the very connection sought between the individual and the group. Returning to Siddhartha, words and teachings build an analogous tension between the particular and the universal, the profane and the sacred.

The crisis of language—the use of words even though they fail—is often considered one of the major tenets of Modernity in the German-language literary tradition. In the works of the Sprachskepsis poets and philosophers of around 1900, language is masterfully used to illustrate its own failing. A fitting example is Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s famous Lord Chandos Letter:

Aber, mein verehrter Freund, auch die irdischen Begriffe entziehen sich mir in der gleichen Weise. Wie soll ich es versuchen, Ihnen diese seltsamen geistigen Qualen zu schildern, dies Emporschnellen der Fruchtzweige über meinen ausgereckten Händen, dies Zurückweichen des murmelnden Wassers vor meinen dürstenden Lippen? Mein Fall ist, in Kürze, dieser: Es ist mir völlig die Fähigkeit abhanden gekommen, über irgend etwas zusammenhängend zu denken oder zu sprechen.51

But, dear friend, worldly ideas too are retreating from me in the same way. How shall I describe these strange spiritual torments, the boughs of fruit snatched from my outstretched hands, the murmuring water shrinking from my parched lips? In brief, this is my case: I have completely lost the ability to think or speak coherently about anything at all.52

In this paradoxical and passionate way, language is used to tighten the tension between what it reveals and conceals, bringing its users and readers to the threshold of language. Hesse’s Siddhartha falls in line with the writings of the Sprachskepsis poets. Consider the strong correlations in language, style and content between the paragon language-skeptic Fritz Mauthner’s Der letzte Tod des Gautama Buddha and Hesse’s Siddhartha. From Der letzte Tod des Gautama Buddha:

Learning is better than teaching. He who believes himself able to teach is scarcely fit to learn. Learning to be silent is the best thing to learn. I would like to be silent, but I should not be silent and I cannot be silent. There is something about the experience of enlightenment that is not speakable in human language, that is not conveyable with words. There is something about suffering, about the emergence of suffering, about the disappearance of suffering, about the path that leads to the disappearance of suffering that is not speakable in language, that is not conveyable with deficient words.53

Lernen ist besser als lehren. Wenig tauglich zum lernen ist, wer lehren zu können glaubt. Schweigen lernen ist das beste Lernen. Ich möchte schweigen, aber ich soll nicht schweigen und ich kann nicht schweigen. An dem Erlebnis der Erlösung ist etwas, das nicht in Menschensprache sprechbar, das nicht in Worten mitteilbar ist. An dem Leiden, an dem Entstehen des Leidens, an dem Verschwinden des Leidens, an dem Wege, der zum Verschwinden des Leidens führt, ist etwas, das nicht in Sprache sprechbar, das nicht in armen Worten mitteilbar ist.54

In Siddhartha there is less of a distinction between »learning« and »teaching«—that is, both are repudiated. But what is profoundly common to both Siddhartha and Der letzte Tod des Gautama Buddha is the complex and paradoxical role language plays in learning, in gaining wisdom, in reaching enlightenment. In both, there is an eagerness to denounce language while using it to express and communicate the ineffable and refer to realms beyond language.

There is an unsolvable mystery throughout Siddhartha: the boy-turned-adult claims to have learned this and that, from here and there, from lover and rock, from money and tree and holy-man, from sensations and the deprivation thereof… But for everything that he learns, he learns that he has learned nothing. And between these poles of learning and not learning, he vacillates continually. At one point, on the riverbank, Siddhartha thinks:

Now that all these utterly transitory things have slipped away from me, he thought, I am left under the sun just as I stood here once as a small child; I own nothing, know nothing, can do nothing, have learned nothing. How curious this is! Now that I am no longer young, now that my hair is already half gray and my strength is beginning to wane, I am starting over again from the beginning, from childhood!55

Nun, dachte er, da alle diese vergänglichsten Dinge mir wieder entglitten sind, nun stehe ich wieder unter der Sonne, wie ich einst als kleines Kind gestanden bin, nichts ist mein, nichts kann ich, nichts vermag ich, nichts habe ich gelernt. Wie ist dies wunderlich! Jetzt, wo ich nicht mehr jung bin, wo meine Haare schon halb grau sind, wo die Kräfte nachlassen, jetzt fange ich wieder von vorn und beim Kinde an!56

So Siddhartha embodies the paradox. At the end of his journey, he is at the beginning; in old age, he is in youth. He has learned nothing, except he has learned that he has learned nothing. In Siddhartha, language is used to show its own as well as learning’s point of critical failure.

Siddhartha, as guidebook, was used in an analogously paradoxical way to reject guidance. The radical individualists of the Counterculture found in Siddhartha reasons to band together and endure because this story helped explain that the questions of language and of learning remained unsolved in their paradoxical quality. They could thereby assert their own, new ways of thinking and of organizing as solutions to this mystery.

Works Cited

CORNILS, Ingo (ed.): A Companion to the Works of Hermann Hesse. Rochester/NY 2009.

ELIADE, Mircea: The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York 1959.

FRIEDRICH, Hans-Edwin: »Rezeptionsästhetik/Rezeptionstheorie«. In: Jost Schneider (ed.): Methodengeschichte der Germanistik. Berlin 2009, p. 597–628.

GARDINER, Patrick: Nineteenth-Century Philosophy. New York 1968.

HESSE, Hermann: Siddhartha. Susan Bernofsky (trans.). New York 2007.

HESSE, Hermann: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung. Frankfurt/M. 1974.

HOFMANNSTHAL, Hugo von: Brief des Lord Chandos. In: Hansgeorg Schmidt-Bergmann (ed.): Poetologische Schriften, Reden und Erfundene Gespräche. Frankfurt/M. 2000.

HOFMANNSTHAL, Hugo von: The Lord Chandos Letter. Joel Rotenberg (trans.). New York 2005.

JAUSS, Hans Robert: »Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory«. In: Elizabeth Benzinger (trans.): New Literary History 2.1 (1970), p. 7–37.

JAUSS, Hans Robert: »Literaturgeschichte als Provokation der Literaturwissenschaft«. In: Rainer Warning (ed.): Rezeptionsästhetik. Munich 1975, p. 126–162.

KOESTER, Rudolf: »Terminal Sanctity or Benign Banality: The Critical Controversy Surrounding Hermann Hesse«. In: The Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association 27.2 (1973), p. 59–63.

LEARY, Timothy and Ralph Metzner: »Hermann Hesse: Poet of the Interior«. In: Psychedelic Review 1.2 (1963), p. 167–182.

MATUSSEK, Matthias von: »Ich mach mein Ding«. In: Der Spiegel, 06.08.2012, p. 124–132.

MAUTHNER, Fritz: Der letzte Tod des Gautama Buddha. Munich 1913.

RAGUSO, Emilie: Occupy the Farm: ›We’ll Keep Coming Back‹, 14.05.2013. http://www.berkeleyside.com/2013/05/14/occupy-the-farm-well-keep-coming-... (last viewed on 27.10.2014).

ROSZAK, Theodore: The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition. Garden City/NY 1969.

SANNEH, Kelefa: Paint Bombs, 13.05.2013. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/05/13/paint-bombs (last viewed on 27.10.2014).

SCHWARZ, Egon: »Hermann Hesse, the American Youth Movement, and Problems of Literary Evaluation«. In: PMLA 85.5 (1970), p. 977–987.

TEPPERMAN, Jean: An Urban Farm Collaborative Grows in Albany, 18.12.2013. http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/an-urban-farm-collaborative-grows-... (last viewed on 27.10.2014).

TYSON, Lois: Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide. New York 2012.

VAHLBUSCH, Jefford: »Toward the Legend of Hermann Hesse in the USA«. In: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik 58.1 (2005), p. 133–146.

ŽIŽEK, Slavoj: The Year of Dreaming Dangerously. London 2012.

ŽIŽEK, Slavoj and Yong-june Park: Demanding the Impossible. Malden/MA 2013.

- 1. By »institutionalization« I refer to its entrance (albeit contentious) into literary canons, its influence over the establishment of cultural institutes (e.g. the inauguration of The Magic Theater in 1967), as well as the scholarly derision it endured (as flung by critics of »Hesse-mania«).

- 2. Hans-Edwin Friedrich: »Rezeptionsästhetik/Rezeptionstheorie«. In: Jost Schneider (ed.): Methodengeschichte der Germanistik. Berlin 2009, p. 619.

- 3. Hans Robert Jauß: »Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory«. In: Elizabeth Benzinger (trans.): New Literary History 2.1 (1970), p. 9.

- 4. Ibid., p. 9.

- 5. Hans Robert Jauß: »Literaturgeschichte als Provokation der Literaturwissenschaft«. In: Rainer Warning (ed.): Rezeptionsästhetik. Munich 1975, p. 126.

- 6. Jefford Vahlbusch: »Toward the Legend of Hermann Hesse in the USA«. In: Amsterdamer Beiträge zur neueren Germanistik 58.1 (2005), p. 133.

- 7. Ingo Cornils (ed.): A Companion to the Works of Hermann Hesse. Rochester/NY 2009, p. 2.

- 8. Jauß: »Literary History« (ref. 3), p. 10.

- 9. Jauß: »Literaturgeschichte« (ref. 5), p. 128.

- 10. Theodore Roszak: The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition. Garden City/NY 1969, p. xiii.

- 11. Hermann Hesse: Siddhartha. Susan Bernofsky (trans.). New York 2007, p. 17.

- 12. Hermann Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung. Frankfurt/M. 1974, p. 20.

- 13. Egon Schwarz: »Hermann Hesse, the American Youth Movement, and Problems of Literary Evaluation«. In: PMLA 85.5 (1970), p. 982.

- 14. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 118–119.

- 15. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 113.

- 16. Rudolf Koester: »Terminal Sanctity or Benign Banality: The Critical Controversy Surrounding Hermann Hesse«. In: The Bulletin of the Rocky Mountain Modern Language Association 27.2 (1973), p. 59–63. He argues that this is »not just in a figurative sense […]« (p. 62).

- 17. Matthias von Matussek: »Ich mach mein Ding«. In: Der Spiegel, 06.08.2012, p. 124–132. »Noch einmal den ›Siddhartha‹, die Henry Miller ›eine wirksamere Medizin als das Neue Testament‹ nannte« (125).

- 18. Ibid., p. 125.

- 19. Timothy Leary and Ralph Metzner: »Hermann Hesse: Poet of the Interior«. In: Psychedelic Review 1.2 (1963), p. 169.

- 20. Ibid., p. 181.

- 21. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 119.

- 22. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 114.

- 23. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 121.

- 24. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 116.

- 25. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 121.

- 26. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 118.

- 27. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 124.

- 28. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 119.

- 29. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 124.

- 30. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 119.

- 31. Mircea Eliade: The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York 1959, p. 20. Hierophany has a long history in Indian tradition, and would be closely related to the Sanskrit term darśana, which refers to the moment of witnessing cosmic universality through the particular. It is a paradoxical vision of formlessness through form.

- 32. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 124–125.

- 33. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 119.

- 34. Eliade: The Sacred and the Profane (ref. 31), p. 12.

- 35. Vahlbusch: »Toward the Legend of Hermann Hesse in the USA« (ref. 6), p. 144.

- 36. Ibid.

- 37. Roszak: The Making of a Counter Culture (ref. 10), p. xiii.

- 38. Ibid. »I have colleagues in the academy who have come within an ace of convincing me that no such things as ›The Romantic Movement‹ or ›The Renaissance‹ ever existed – not if one gets down to scrutinizing the microscopic phenomena of history. At that level, one tends only to see many different people doing many different things and thinking many different thoughts. How much more vulnerable such broad-gauged categorizations become when they are meant to corral elements of the stormy contemporary scene and hold them steady for comment!« (xiii)

- 39. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 125. English trans. by A.M.

- 40. Patrick Gardiner: Nineteenth-Century Philosophy. New York 1968, p. 291.

- 41. Roszak: The Making of a Counter Culture (ref. 10), p. 41.

- 42. Slavoj Žižek: The Year of Dreaming Dangerously. London 2012, p. 33.

- 43. Slavoj Žižek and Yong-june Park: Demanding the Impossible. Malden/MA 2013, p. 6.

- 44. Matussek: »Ich mach mein Ding« (ref. 17), p. 126. »Hermann Hesse hätte die Idee der Occupy-Bewegung begrüßt, sicherlich, weil sie Sand ins Getriebe zu werfen versucht, aber doch keine Zeltstadt! Nie hätte er gemeinsam mit anderen Parolen gebrüllt! Programme, sagte er, seien für Dumme und Einladungen zum Missbrauch« (126).

- 45. Kelefa Sanneh: Paint Bombs, 13.05.2013. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/05/13/paint-bombs (last viewed on 27.10.2014).

- 46. A tangential line of inquiry: How does the term Anarchy practically function? If the state is held to be unnecessary, if there is to be no law, no rule and no ruler, then how does Anarchy view its own anarchic organization? How does it view its symbols, the circle-A and the black flag, or its mottos and iconic figures, if not as ideological symbols meant to organize (even if meant to organize decentralized disorder)? If Anarchy were to catch on, would not Anarchy become the very rule against which the fight would be fought, still in the name of Anarchy? Is there a better term?

- 47. Sanneh: Paint Bombs (ref. 45).

- 48. Jean Tepperman: An Urban Farm Collaborative Grows in Albany, 18.12.2013. http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/an-urban-farm-collaborative-grows-... (last viewed on 27.10.2014).

- 49. Emilie Raguso: Occupy the Farm: ›We’ll Keep Coming Back‹, 14.05.2013. http://www.berkeleyside.com/2013/05/14/occupy-the-farm-well-keep-coming-... (last viewed on 27.10.2014).

- 50. Lois Tyson: Critical Theory Today: A User-Friendly Guide. New York 2012, p. 253.

- 51. Hugo von Hofmannsthal: Brief des Lord Chandos. In: Hansgeorg Schmidt-Bergmann (ed.): Poetologische Schriften, Reden und Erfundene Gespräche. Frankfurt/M. 2000, p. 131.

- 52. Hugo von Hofmannsthal: The Lord Chandos Letter. Joel Rotenberg (trans.). New York 2005, p. 121.

- 53. Trans. by A.M.

- 54. Fritz Mauthner: Der letzte Tod des Gautama Buddha. Munich 1913, p. 80–81.

- 55. Hesse: Siddhartha (ref. 11), p. 80.

- 56. Hesse: Siddhartha. Eine indische Dichtung (ref. 12), p. 78.

Add comment