Digital Journal for Philology

Combining Digital Scholarly Edition with Heritage Literature Representations: Learning from Garrettonline’s Experience

1. Introduction: The Need of a New (Digital) Edition of Almeida Garrett’s Romanceiro

From England, where he went into exile for political reasons, Almeida Garrett, a leading figure of the first Portuguese Romanticism, planned to restore Portuguese culture and literature, in general. He did so, then, inspired by the German Romantic philosophers (Johann Gottfried Herder, Jacob Grimm, Friedrich Schiller, etc.), but also by the Balladist movement of English and German editors of his own time, e.g. Walter Scott, Thomas Percy or Friedrich Christian Diez.

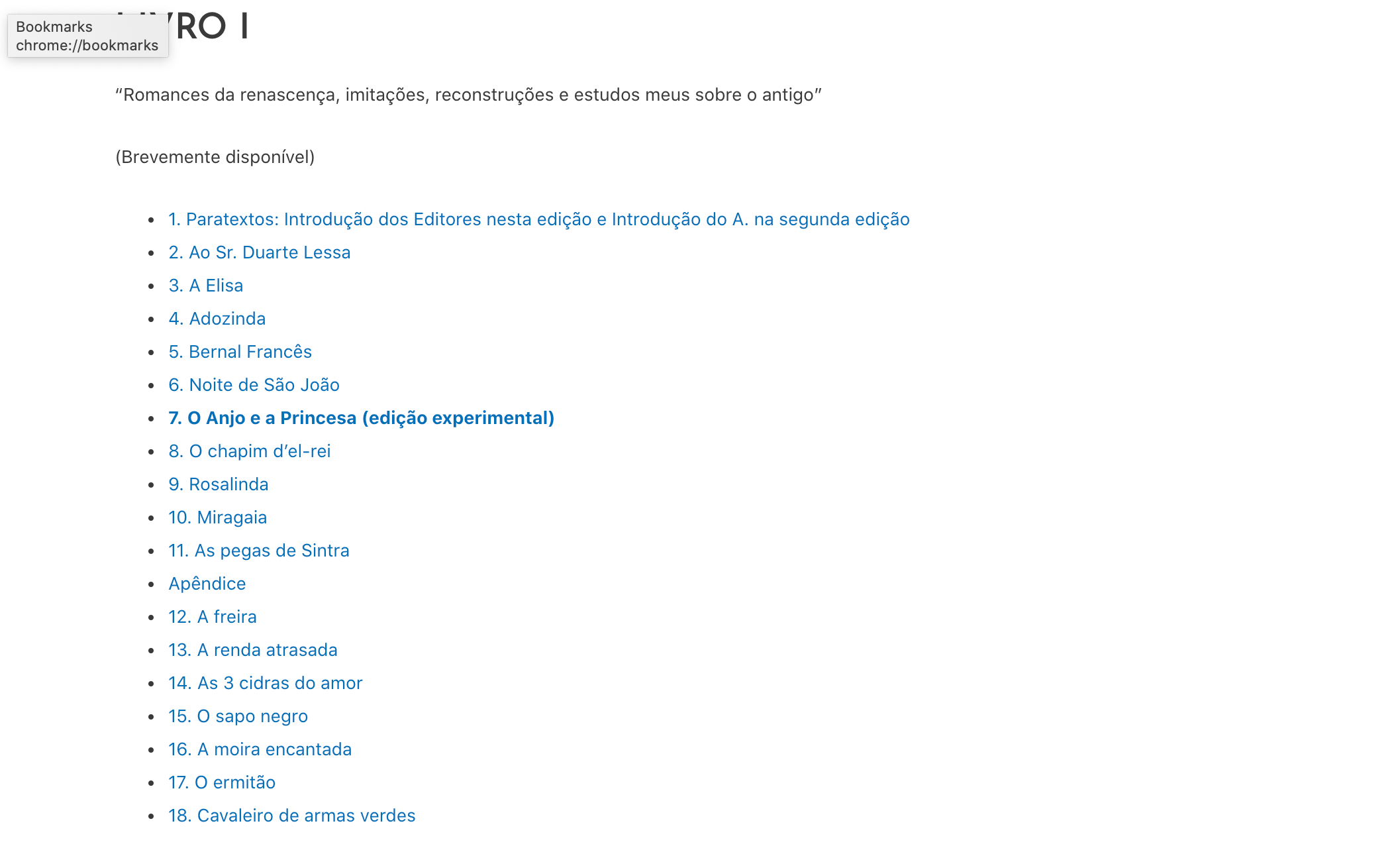

Indeed, in 1828, on Garrett’s initiative, for the first time a small set of folk ballad versions – known as romances in the Iberian context – was published in the Portuguese language.1 He entitled it Adozinda. Romance. Then, in 1843, the same editor and poet published the volume Romanceiro e Cancioneiro Geral – which he considered his collection’s first book. The second book of the Romanceiro – in two volumes – saw the light of day in 1851 with the aim of providing the new Romantic poets a quality set of national subjects to be adapted and converted into Romantic ballads. Later, in 1853, Garrett reprints his Book I from 1843. To this new print, he adds a few more poems of his own imagination, drawing on folk motifs and source texts. He also renamed the book: it was entitled Romanceiro, I. Romances da Renascença.2

Here we have the printing history of the Romanceiro by Garrett’s hand. As far as one can see, it is not a complex one. However, there is a very important detail that cannot be forgotten, and it is that Almeida Garrett’s folk balladry work remained incomplete. It is due to his early death that he did not complete the editorial plan for the five books presented in the »Introduction« to Volume II of his Romanceiro.3

The editing path of Almeida Garrett’s Romanceiro has been very successful since the work soon became a notable piece, not only of the Portuguese but also of the Iberian literary heritage, due to its absolutely innovative approach. Garrett was, concerning the Iberian region, the trailblazer of the modern folk balladry editorial movement. Nevertheless, from a strictly ecdotic point of view, the hundreds of reprints we may identify are not of value from a philological point of view. Despite this, it is worthwhile to recall the manuscript tradition in order to fully address the philological questions raised by the Romanceiro work. An autographed notebook started in 1824, the Cancioneiro de Romances, xácaras, solaus […],4 preserves 26 previous versions of Garrett’s folk ballads, but philologists were already aware that most of Garrett’s manuscripts were still missing. Although it was impossible to get ahold of the field originals where oral folk versions were to be written down, it was at least desirable to recover the author’s ›originals‹ or at least the textual witnesses that would allow us to understand in some way our poet and editor’s creative procedures.

Recently, in 2004, some 400 autographed manuscript pages by Garrett relating to his Romanceiro work were found coincidentally in a private residence in Lisbon:5 we named it the Futscher Pereira Collection. Currently, the General Library of the University of Coimbra (Portugal) preserves these autographs next to some of Garrett’s previous autographs devoted to his folk balladry publication project. Of course, together, the sum of the manuscripts identified launch an interesting set of questions regarding their genetic significance. On the one hand, they play a very significant role in the Portuguese literary scene due to their cultural value, but there is much more. In fact, they literally document the artistic thinking of one of the leading figures of 19th century Portuguese cultural life. On the other hand, these manuscripts contain older traces of Portuguese folk balladry from the 19th Century folk transmission – what we usually call the ›modern tradition‹.

Based on this, we have been researching, from a critical and genetical approach, the creative path of the Romanceiro poems – 99 folk ballad versions, to be precise –, aiming for a twofold editorial goal: 1) to stress their inherent heritage value as a cultural good; and 2) to put forward their dynamic and somehow tense relationship between the folk oral tradition and the creative authorial Romantic poetry.

That said, we may suspect that such a complex mix of editorial goals shall not fit into a traditional printed scholarly edition. Let us analyse, then, to what extent it is appropriate to dive into the environment of digital scholarship. In addition, we devote the following pages to some theoretical aspects we have been discussing alongside the editorial project – Garrettonline6 – since its starting point in 2013.

First, we will look at the methodological framework of the Garrettonline project (2.), which provides stimulating approaches to the relationships between an archive and a scholarly edition. We will combine them with a refreshing topic, which is addressed by the particular openness of folk balladry. Following this, it is worth drawing attention to a particularity of the digital edition of the Romanceiro, which is to merge ›the illusion of the finalism‹7 with the unstable state of the romanceiro itself. (3.) At this point, we will go deeper into questions referring to our digital environment and infrastructure. Particularly, we will approach how the traditional scholarly editing workflow has been adjusted to a digital scholarly workflow, insisting on its consequences and requirements. Likewise, visualization as an engagement to simplification and adaptation will be addressed in accordance to Garrettonline’s editorial research.

2. Archive, Edition and the Romanceiro Openness

2.1. Editing a Folk Ballad in the Digital Realm

A significant evolution has taken place since 2009, when José Manuel Lucía Megías insisted on the need to overcome the »incunabula« of hypertext on digital editing.8 The defense of editing »as a space of knowledge« referred to by Professor Lucía Megías in said study, that is, the challenge of creating »thought structures«9 that allow the users to connect with the editorial materials from different perspectives, totally breaks with the topography and with the scope of all ecdotic work, as we have known it at least since the 19th century.

As far as the Romanceiro is concerned, we should not forget that we are dealing with an open genre by default due to the variation provided by its oral transmission. Moreover, we recall its performative nature. That is why the various currents of textual representation are still concerned today with the principles for the philological treatment of a romance.10 What criteria should we use to represent the variation inherent in each oral version of a folk ballad in a critical edition? It is true that ecdotics provides us with very useful editorial guidelines. In any case, no one doubts that setting an oral version – which, by the way, is often sung – entails significant losses. This becomes particularly clear when compared with the far easier consequences of producing a critical or genetic edition of a canonical text, i.e., a text without any oral or traditional influences.

Any editor who has recorded a folk ballad – which is itself an act of remediation –, in some audio or audiovisual medium during a field survey, is aware of these issues. And there is no doubt that the concerns related to these losses are therefore linked to the multimodal and unstable dimension of traditional oral ballads.

At this point, it seems appropriate to reflect on the use of concepts, methodologies and digital tools to examine the extent to which the digital philological paradigm adds value, or rather provides a positive approach, to the representation of folk ballad texts. We must bear in mind that a significant part of the romances edited by Almeida Garrett in 1828, 1843, 1851 and 1853 have strong links to traditional oral ballads. As I have written before:

One could manage to recover the multiple and necessarily rich nature of a folk ballad version in its essence, thus, through a digital edition whose technology would allow a more fruitful approach to the original multimodal nature of the folk text. Taking advantage of the digital paradigm strategies such as hypertext will allow us to represent the folk textual variation and at the same time will give access to an endless number of resources.11

In addition, a radial approach that combines different editorial goals produces what should be an edition of a folk ballad as I conceive it. In other words, implementing a paradigmatic edition of ballads in a digital environment would lead us to the same open and variable nature of the ballads themselves that we mentioned earlier. But – and this is a key point – the multiplicity of views that digital philology allows is based on an innovative assumption: that the editio variorum and the editio ne varietur of a romance will be no longer incompatible. This is something that the non-digital editorial paradigm does not allow for at all.12

In order to comply with this later proposal statement, we want to introduce two neuralgic concepts into our discussion. We refer to scholarly editing as an ›archive‹ and the concept of ›assisted reading‹.

2.2. Archiving Romanceiro’s Textual Memories

Over the last four decades, a new look at the romanceiro genre has developed in the Iberian context, even if the great efforts of the couple Ramón and María Goyri Menéndez Pidal, who were mainly active in the first half of the 20th century, were the beginning.

When approaching the ballads from the point of view of heritage, we shall consider a double dimension of the folk poetic genre which is truly exceptional: the more we recognize it as heritage poetry – it is no one person’s creation, but at the same time it belongs to each and to every of its owners – the more we identify an undeniable heritage value in the archives, collections and editions. In Portugal, the origins of this editorial push go back precisely to the pioneering work of identifying the genre that Garrett did in the early 19th century. A great sum of text, image and audio files have been produced since the early 19th onwards, whether they are analogue or, recently, digital. To date, philology and documentary sciences merge into a single objective: to preserve memory. At the Garrettonline project, we preserve the ballads’ memory as much as the memory of their memory – e.g., images of manuscripts and printed materials, copies, textual encoding, photographs, etc.

Thus, the Portuguese philologist Luiz Fagundes Duarte – who has done great work in the scholarly editing of some of the most canonical Portuguese authors, such as Fernando Pessoa or Eça de Queirós – has linked the concept of ›archive‹ to the concept of ›cultural heritage‹, which he understands as a memory store. Also, in his recent studies on ›manuscriptology‹ he has dealt with the new role of the philologist. He states that:

[…] It will be most necessary that an old character with an official recognition comes to contribute – now with a new role – to help the overwhelmed technical staff which nowadays hold the responsibility for the most direct gathering, classification, preservation and valuation of bibliographic heritage that, on a daily basis, will be incorporated into our libraries and archives: the philologist.13

There is no evidence that Luiz Fagundes Duarte had the digital paradigm in mind, and, precisely because of it, his comment seems even more appropriate. However, it should be remembered that the importance of philology in the preservation of bibliographic heritage, bearing in mind above all the »philology of the present original«,14 is a phenomenon that has been seen from different angles, but from genetic criticism in a particular way. Besides this, it is worth adding that the research work devoted to authorial archives have undoubtedly benefitted from digital technology. Indeed, the concept of philology as an »archival memory« was properly established by Jerome McGann,15 also supporting our edition’s methodological approach. Let us now discuss how this works within the Garrettonline project.

As I have previously argued,16 one of our general editorial research goals is to understand the extent to which current digital technology provides suitable means for creating an edition archive for Almeida Garrett’s Romanceiro. To achieve this, we have pursued the following guidelines, which are of course not feasible in a print edition:

a) to present to a common reader, and at the same time to a professional, a rigorously established text that represents – or at least approximates – the author’s ultimate will for the Romanceiro and for each of its texts;

b) to provide different levels of reading according to the interests of each reader.

In fact, Garrettonline’s editorial proposal seeks the reconstruction of the textual witnesses and ensures the access to any facsimile document linked to it. On a future basis, improvements will be made to the digital platform towards the reconstruction of Almeida Garrett’s oral balladry sources. We refer to a work by philological rapprochement between erudite and traditionally tailored ballads, as presented by Ferré’s methodology.17

Let us elaborate on the theoretical impact of Garrettonline’s editorial principles. It is about to achieve, in a single digital artefact, a status described by Peter Robinson: »a scholarly edition must, so far as it can, illuminate both aspects of the text, both text-as-work and text-as-document«.18 As we suggested before when we called upon the meanings of heritage preservation, our edition claims, on the one hand, to the preservation of both material documents and, on the other hand, to the preservation and availability of texts and of a whole literary work which additionally is meant to be reconstructed. Therefore, we deal with different levels of concepts we need to combine in a single digital edition: document, text and work.

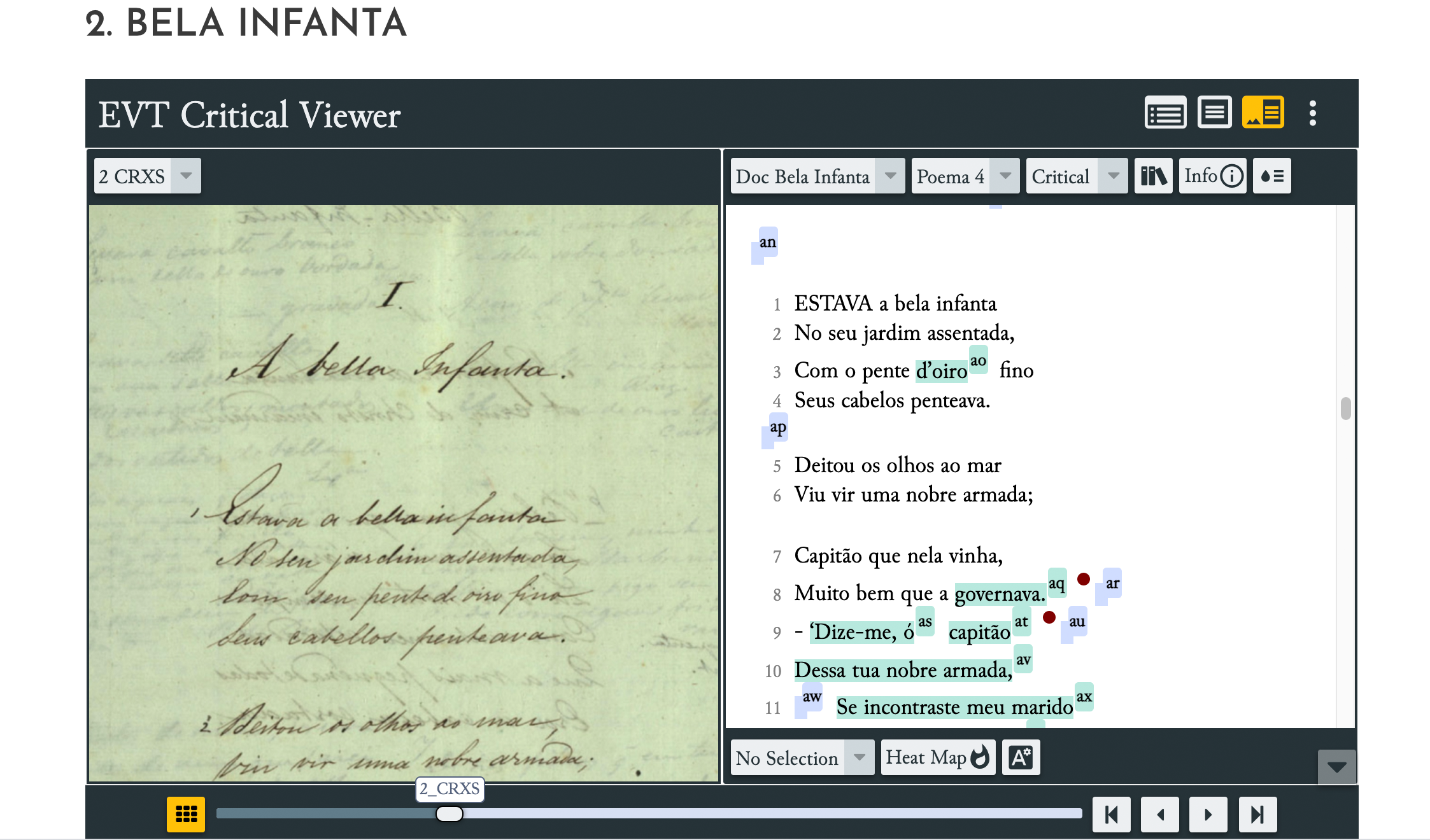

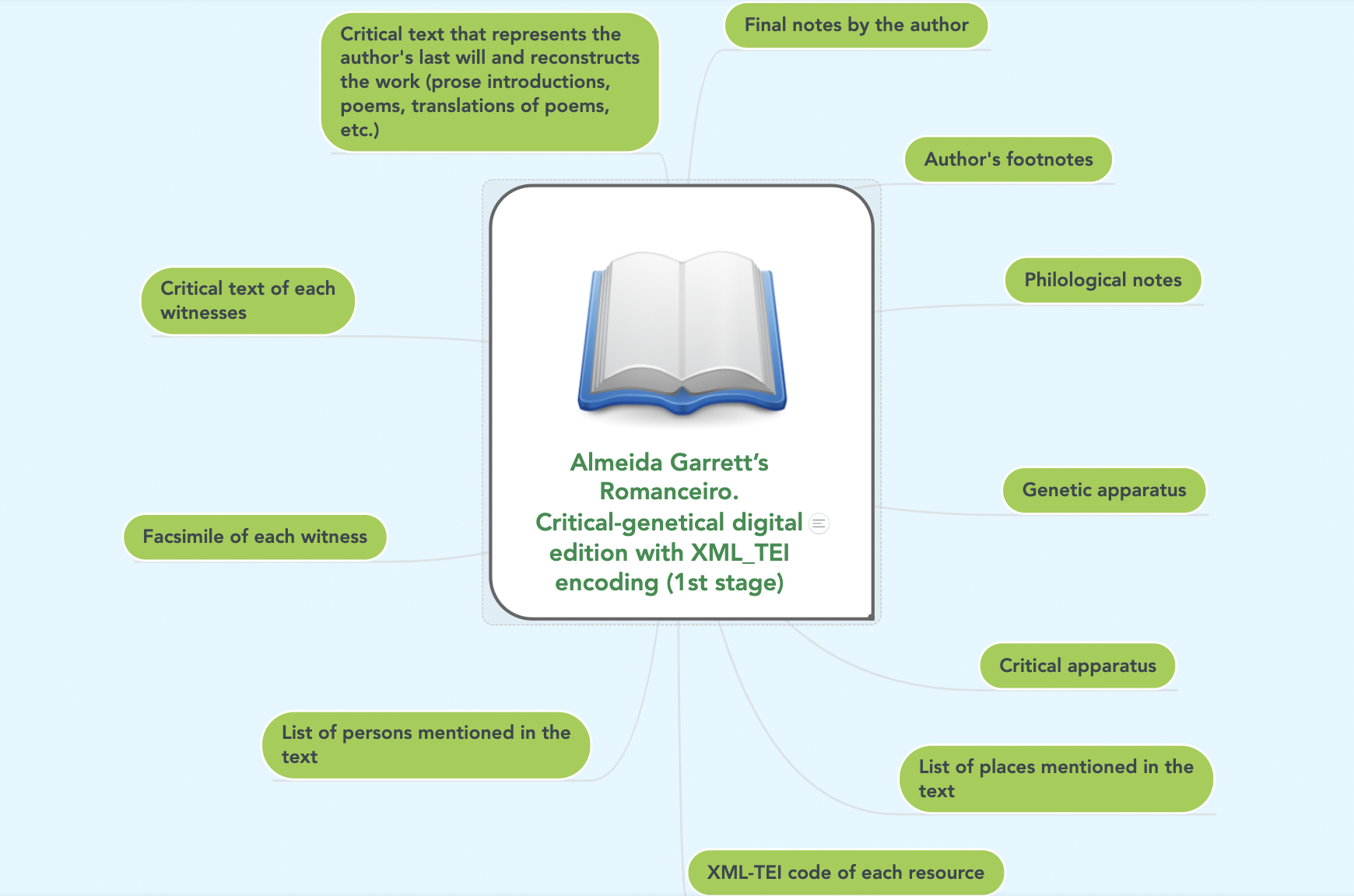

Figure. 1: Document – text relationship.

Figure. 2: Work – text relationship.

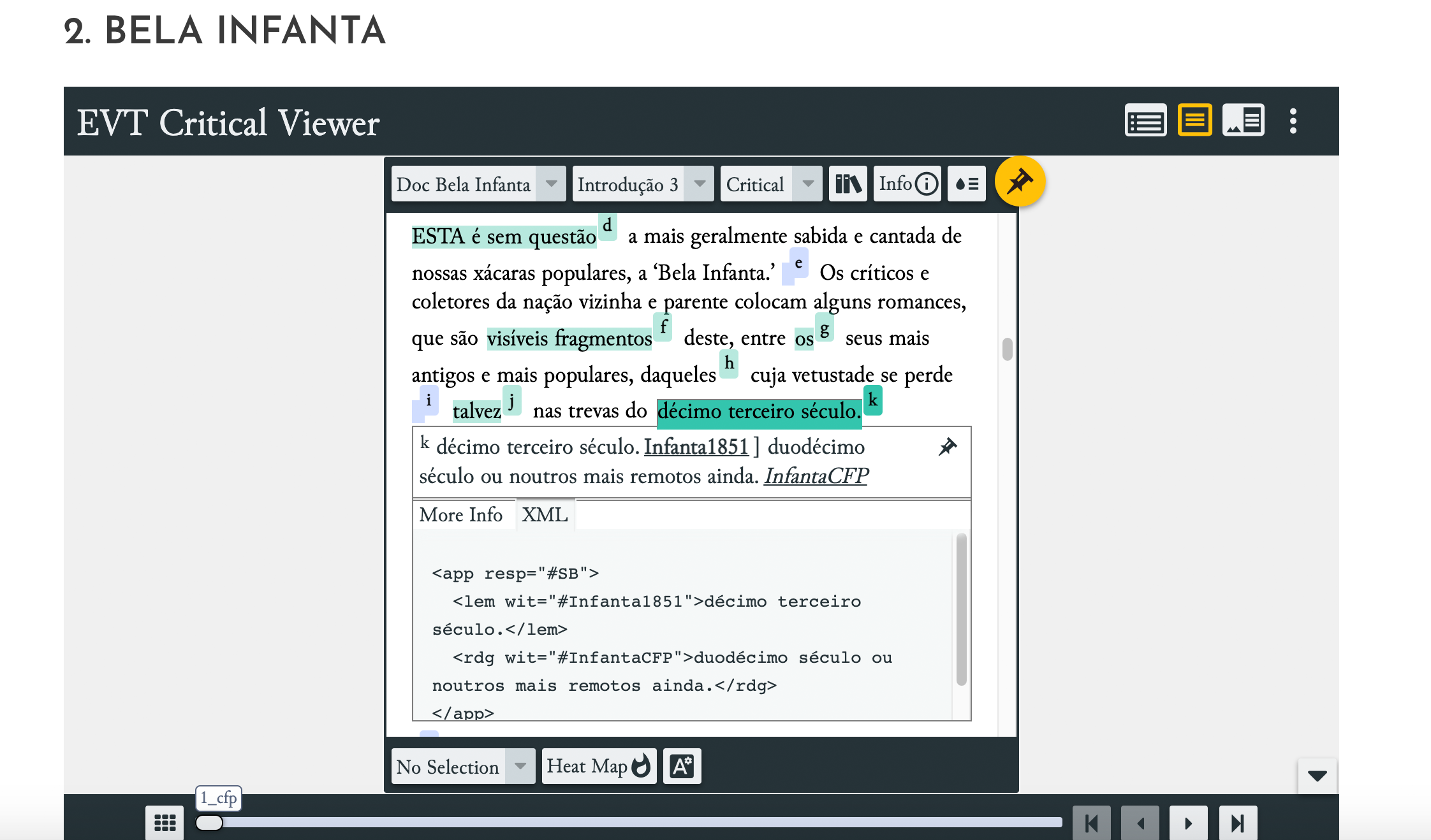

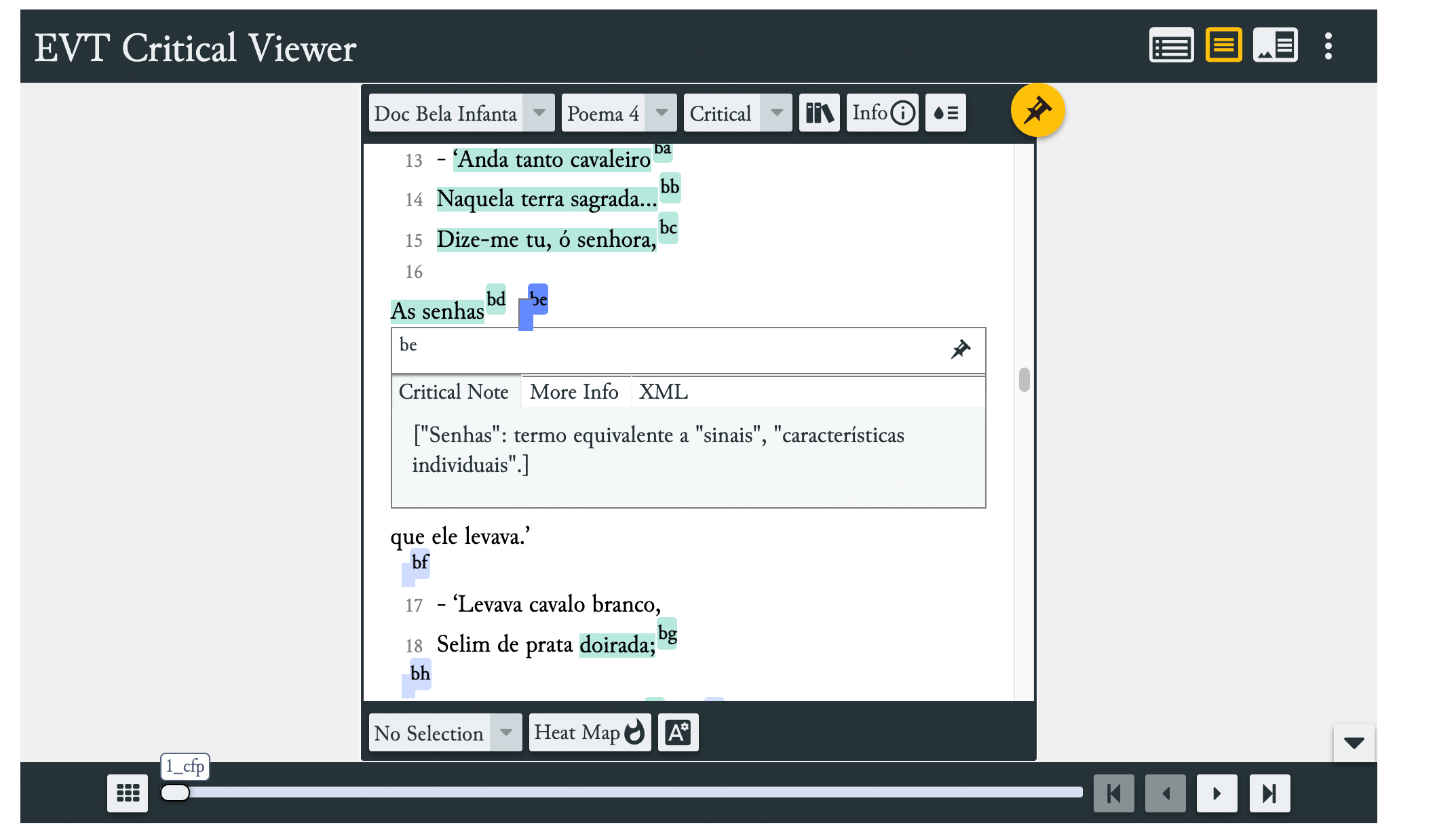

Additionally, referring to the ›text level‹, it is mandatory to add that each poem offers other particular editorial textual features: the critical and genetical apparatuses which are not in line. Instead, they open up by means of a reader’s action, to whom we also provide the apparatus encoding, as the following figure illustrates:

Figure. 3: In order to activate the genetical apparatus, readers click on the colourful variant; they also get access to the variant encoding.

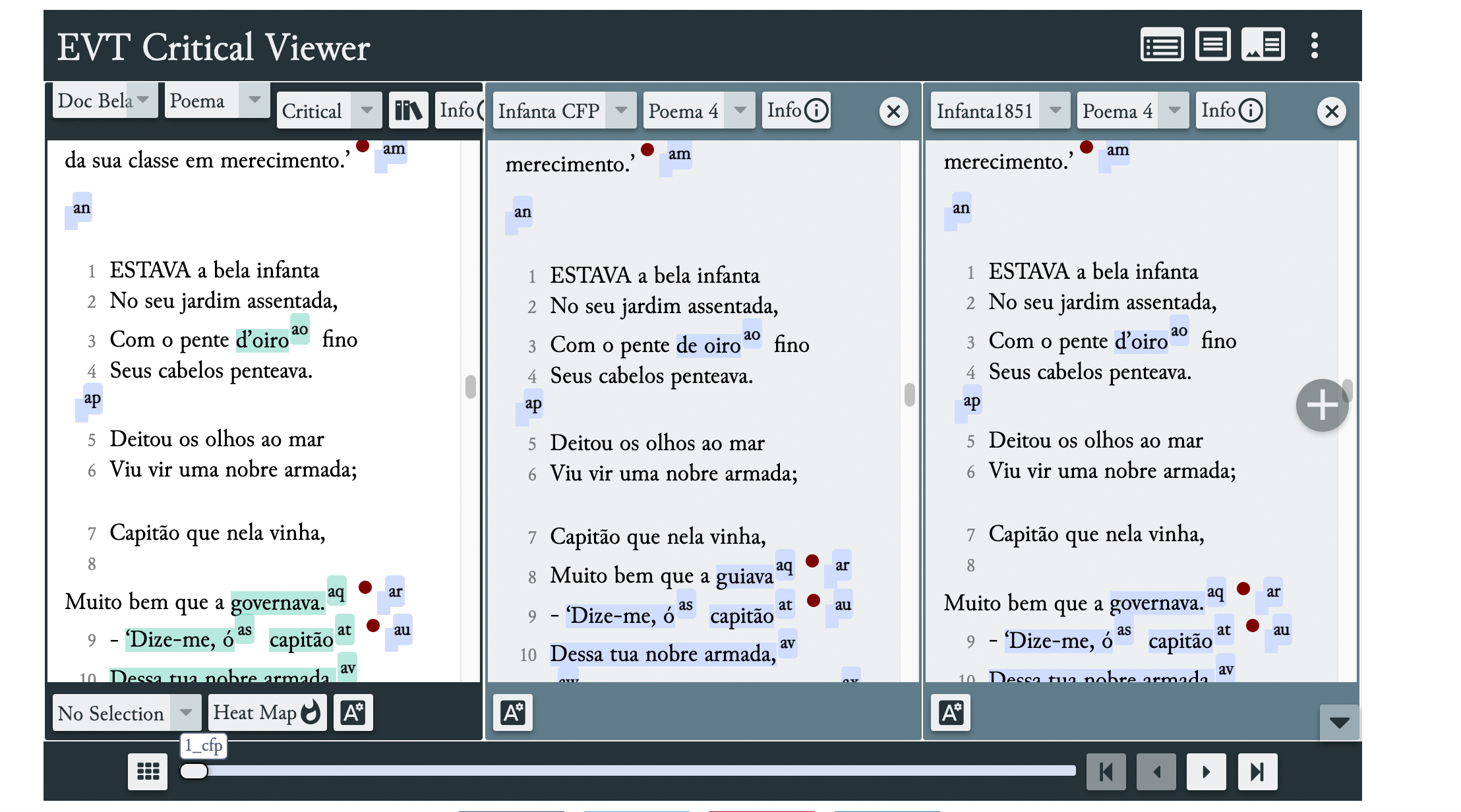

Moreover, in our editorial archive, the reader has the possibility to select a ›reading text‹ of his or her own choice among different possibilities we offer on the platform. The critical text and each witnesses’ texts are all available.

Figure. 4: The paradigmatic edition, where the critical text (first window) comes side by side with the witnesses’ texts.

But still concerning digital textuality, the ground-breaking feature of our edition may reside in the proposal of a ›would-be-text‹ that will complement each one of the edited ballads. It is thus a text that consists of reconstructing a folk ballad version that Garrett might have received from oral tradition, i.e., a conjecture based on a collation of a number of folk versions gathered in the Romanceiro.pt archive.19 This kind of archetype allows us to fill a philological gap often attributed to the editors of romantic folk ballads. As they manipulate their oral text sources, many doubts remain about the original form of the texts. Therefore, an automatic or semi-automatic collation seems to be the most appropriate method to propose this ›original‹ text. There is no doubt that this novelty of the ›would-be-text‹ has the potential to have a great impact on improving our complex digital textuality, along with all the other levels we have mentioned.20

In short, the following conceptual map embodies all the features we came to define at the level of digital editorial modelling. Indeed, the radial approach we mentioned before becomes easily observable as much as the archival infrastructure.

Figure. 5: The digital archive conceptual map.

3. Digitally Combining the Illusion of Finalism with the Unstable Condition of the Romanceiro

3.1. The Final Text and the Representation of the Writing Process: Different Goals in a Single Digital Editing Environment

Without going any further, it is worth remembering that Garrett died leaving the Romanceiro publication plan incomplete, as we stated in the beginning. In spite of that, now we have access to 45 new poems that the author prepared for publication, though some of them were left in a very primitive form. For this reason, the Garrettonline project has taken up the challenge of including these unedited poems in the edition in accordance with the author’s instructions.

Our texts’ arrangement and their attribution to a certain Book hold a serious intervention in the Romanceiro device seeking to observe, in first place, the author’s intent in this regard. We refer to the Books that were never printed or even organized with certainty (Books III, IV and V). So, the edition scope must take the task to (re)create the work, under conjecture. To be honest, we find this to be the most difficult and risky philological exercise we can undertake, even if we anchor it in the recovery of the usus scribendi and of the author’s intentio.21 Our criteria are mostly based on the notes that Garrett wrote down on his autographs. They often mention the romance’s subject and even its original date, which have been defined according to Garrett’s own peculiar Romantic scheme, and which we combine with the description of his last publishing plan.

That said, the philological intervention that we propose and, therefore, the expansion of the Romanceiro work ope ingenii, results from the study of the autographs, the pre-textual phases or, in any case, the last known stage of a text from a genetical approach, in compliance with the notions that »There is no definitive version but later«22 and that »[...] criticism is not an edition that simply reprints a text and cleans it of misprints.«23

3.2. The Need for a Digital Approach

In a previous stage of the digital project, which began in 2013, we primarily defined our ecdotic workflow along three axes:

1) that our demands towards the critical edition of Garrett’s Romanceiro sought to mix up very different philological and media resources;

2) that, due to its complexity, it could never be performed as an analogue edition, but, on the contrary, it might be conceived and developed from the digital paradigm;

3) that the use of text markup standards was mandatory, specifically the Text Encoding Initiative standard, in its P5 version, based on XML – extensible markup language –, which of course has the enormous advantage of separating the content and its presentation.

Let us go further into Garrettonline’s edition features now so that we can properly evaluate their consequences concerning the textuality issue. Although its centre is the critical-genetical text, we claim that we must represent the long chains of variation that Garrett’s texts reveal. One can perceive these chains in different textual materials and, in particular, when looking at the processes that have contributed in some way to display each one of the proposed critical texts. We refer to oral modern ballad versions as well as to old romances (Garrett’s sources, each of them with its variation). We also refer to the genesis of Garrett’s texts and their creative process, reflected on manuscripts and other pre-textual materials. Finally, we refer to accessing a critical text that takes into account the creative processes which the edition might represent digitally, and, alongside, to the representation of those same processes which must remain available to the edition’s audience.

This is where the true divide between a digital and a printed critical-genetical edition becomes apparent: we argue it lies on the attractive, multimodal and hypertextual efficient display devices that the digital environment offers. Moreover:

[…] Doing things digitally is not simply doing the same in a new medium. […] This new medium requires a fair bit of theoretical rethinking and reflection on the significance of what we are doing and its impact on the discipline and on our notions of textuality.24

Besides that, the authors point out that »[e]lectronic texts have an even larger degree of changeability, and digital editing therefore forces editions finally to embrace textual variation as a defining feature of textuality«.25 It seems crucial, then, to emphasize the notion of a digital textuality that represents a certain textuality – the ballads – which, by its very nature, in the case of our work is already extremely fluid.

Thus, focusing on Garrett’s corpus and on our editorial demands we came to discuss before, there is no chance to reject, from a conceptual point of view, the digital editing as the most appropriate representation model to the full textual creation process of Garrett’s ballads. We believe it is clear now the need for the digital technology to represent the work and everything else we intend to reveal as a result of it. It is not about choosing a new dissemination channel, since we consider it the least significant demand of all. It is rather about taking advantage of the conceptual and also technological opportunities that the digital realm provides, e.g., the semantic and structural representation of the texts; the all-in-one documental, genetical and critical edition’s levels; the reformulation of the notion of what a text can be. The later achievements of the digital philology respond better than before to old requirements, all in all.

The implementation process we have been working on since 2013 has led us to understand the editorial project as a research space in its own right. In other words, the edition process is not only a complete final result which is the digital edition, but rather the process of conceptualization, the problems’ approach and the search for solutions as much as the partial and provisional results that we achieve. Everything is framed under the concept of editing as a »research site« referred to by Gabler.26

In this way, we have drawn firstly a conceptual workplace which has lately been turned into a digital artefact in 2018: we refer to the Garrettonline website. The project’s website pursues different goals: on the one hand, it seeks to feed up a physical presence on the web, a virtual place where the expert or reader who is interested in these topics can find basic information about the project.27 On the other hand, the most remarkable aspect directly referring to the Romanceiro‘s work is that the critical-genetical edition can be accessed from the ›Home‹ page of the website itself. By clicking on each of the five icons representing some of Romanceiro’s autograph manuscripts, the user can directly access the critical reconstruction of each of the five Books that we have planned, according to what was previously discussed about the reconstruction of the Romanceiro as a work. Afterwards, from this point the user can specifically access each one of Almeida Garrett’s texts. At the same time, each of the poems’ titles leads us to the editorial infrastructure itself. One may realise, then, that the website itself enhances, through its hyperlink structure, the hierarchical but non-linear access to all the editorial features and functions that we have been describing. Because in order to access the editorial contents one must browse the site’s multiple hyperlinked resources, it is useful to recognize that the notion of ›user‹ is more appropriate to our edition than ›reader‹ can be. And no doubt that this feature goes in line with the recent conceptual advances that experts recognize concerning digital scholarly editions.

3.3. The Methodology of Digital Scholarly Editing

To the present day, and despite the significant developments that we have experienced in the world of digital ecdotics, there is something that has not yet changed: »it is not usually possible to replicate the same workflow as the one used for printed editions […]«.28 Our own experience confirms that, when designing the workflow of a digital edition, the sum of time and efforts is truly tremendous. Furthermore, any wrong decision at some point of the workflow has very serious consequences and can even spoil the work already developed. So, at Garrettonline, we have devoted years to the creation and stabilization of this process. In defining the workflow, we focused on two key digital principles:

1) to adapt: the convergence of textual criticism’s classic scheme with the digital edition’s framework and specific goals, in order to automate, within the limits and peculiarities of our corpus, the philological work;

2) to simplify: at a later stage, adapting these methodologies to the search for a proper visualization as well as defining a strategy for the edition’s curation and usability in line with our goals; this has forced us to some adaptations and to take particular assignments.

Indeed, we have been able, throughout this brainstorming, to fully confirm Rosselli Del Turco’s words.29 He regrets that:

When embarking on a digital edition project […] one has to start walking on an unfamiliar and possibly intimidating path, whose final destination may not be fully known in advance […] there are often unexpected changes that the editor needs to be ready to perform so that the project can safely be concluded and an edition published.

As a result, let us start by discussing and detailing these two stages of Garrettonline that we referred to just above.

1) To adapt:

Regarding the adaptation action, a vast bibliography set has already recognized that:30

The diverse computational procedures that have to be carried out, from the witnesses’ transcription to the edition’s visualization, force the scholarly editor to be permanently skipping from a format to another, from a tool to another without any connection between them, and, as a result, the work simply returns to a manual procedure in some cases.31

Indeed, we already had the opportunity to comment step by step on the adaptation to our digital edition’s framework of the editorial process established by Professor Blecua in his Manual de Crítica Textual.32 It is worth remembering Blecua’s editorial steps: 1. Recensio; 2. Fontes criticae; 3. Collatio codicum; 4. Examinatio and Selectio; 5. Dispositio textus; 6. Apparatus criticus. In Garrettonline’s particular scheme, we added a 7th last step, which we called ›Collatio between Garrett’s final will about the poems and the folk versions‹.

It should be noted that steps 1 and 2 were carried out within the framework of the study of Garrett’s romanceiro sources.33 In this crucial step, a great effort has been done. In fact, after documenting, organizing and studying exhaustively the textual sources of the Romanceiro, we were able to propose a dispositio of the ballads along the five Books that our website rebuilds under conjecture through a hypertextual approach.

Step 3, which deals with the collatio codicum, is »one of the most delicate [stages] of the entire editorial process«, as Professor Blecua once noted himself.34 It is not necessary to insist on how tough this task is, assuming that every critical editor relies on the product of his or her collation in order to present his or her editing proposal. Bearing that in mind, an attempt has been made, within the limits we have already discussed,35 to automate it, in order to reduce time consumption and, consequently, the failure risk. After studying diverse digital tools such as CollateX36 or Juxta Commons37, we came to conclude that none of them offered the range of outputs that CollateX does.

On the other hand, although this is not the proper place to discuss practical encoding questions, steps 5, 6 and 7 are implemented using XML-TEI markup. That is, all textual material is encoded.

Eventually, step 7 did the real innovation in our editorial workflow. It is a second collation that compares, with a rather archaeological approach, Almeida Garrett’s texts with the texts collected from the modern Portuguese oral tradition which are available in the Arquivo do Romanceiro em Língua Portuguesa.38 By this procedure we will achieve a hypothetical poem closer to an oral archetype of a romance, through the study of the author’s creative resources, but in the opposite motion: our starting point is the final lesson of Garrett’s poem which was inspired by a version or more than one version of traditional romance. Departing from here, we go backwards for the sake of reaching the oral voices. At the same time, we put the emphasis on the meaningful variants and on the creative processes, with the aim of combining the final product with the process in the digital edition level.39

2) To simplify:

The simplification process points to a later phase in the project’s agenda, drawn around 2019. Our practical concerns on the digital infrastructure and, in particular, on how to approach the edition’s display were finally on the table. What tools to choose in order to reach the editorial goals?

Just like we argued, the digital remediation entails losses of information throughout the process. We referred, then, to the adaptation and simplification tasks as we have euphemistically named them, since there was no choice but to adapt our methods and practices to the new environment. In addition, as we will detail below, it should be simplified according to the requirements of the different tools, formats and outputs that are handled and generated throughout our edition.

Likewise, around 2019, we took on the delicate task of adapting the above-mentioned editorial strategy to a visualization technology that still needs to be discussed here. Above all, again there was no other option but to simplify it.

Since our corpus is made up of 99 poems and a considerable number of prose paratexts, we preferred to start by trying to organize the ›dossiers génétiques‹40 of the published part of our Romanceiro. It should be added that the task of the sources’ digital organization reflects the results already reached,41 where for the first time the Romanceiro edition is conceived from the point of view of its genetic sets (the dossiers), although it is not reached to specify these sets but only to draw them from an abstract point of view. Actually, this task is, above all, aimed at helping the text's markup with TEI-XML and, at the same time, filling in the digital visualization infrastructure that we will detail below. In this way, each one of the sets collects all the images of the facsimiles that compose it (whether printed, handwritten or mixed) from one or several text files containing the edition itself – in some cases we refer to multiple files since the text is followed by notes spread throughout other parts or volumes of the work. In addition, they gather the XML file that will be uploaded to the visualization platform and that contains the digital edition of all the textual sections shaping the textuality concept.

Considering the great sum of texts that constitute our corpus,42 it was mandatory to define how to approach the text markup in a structured manner.

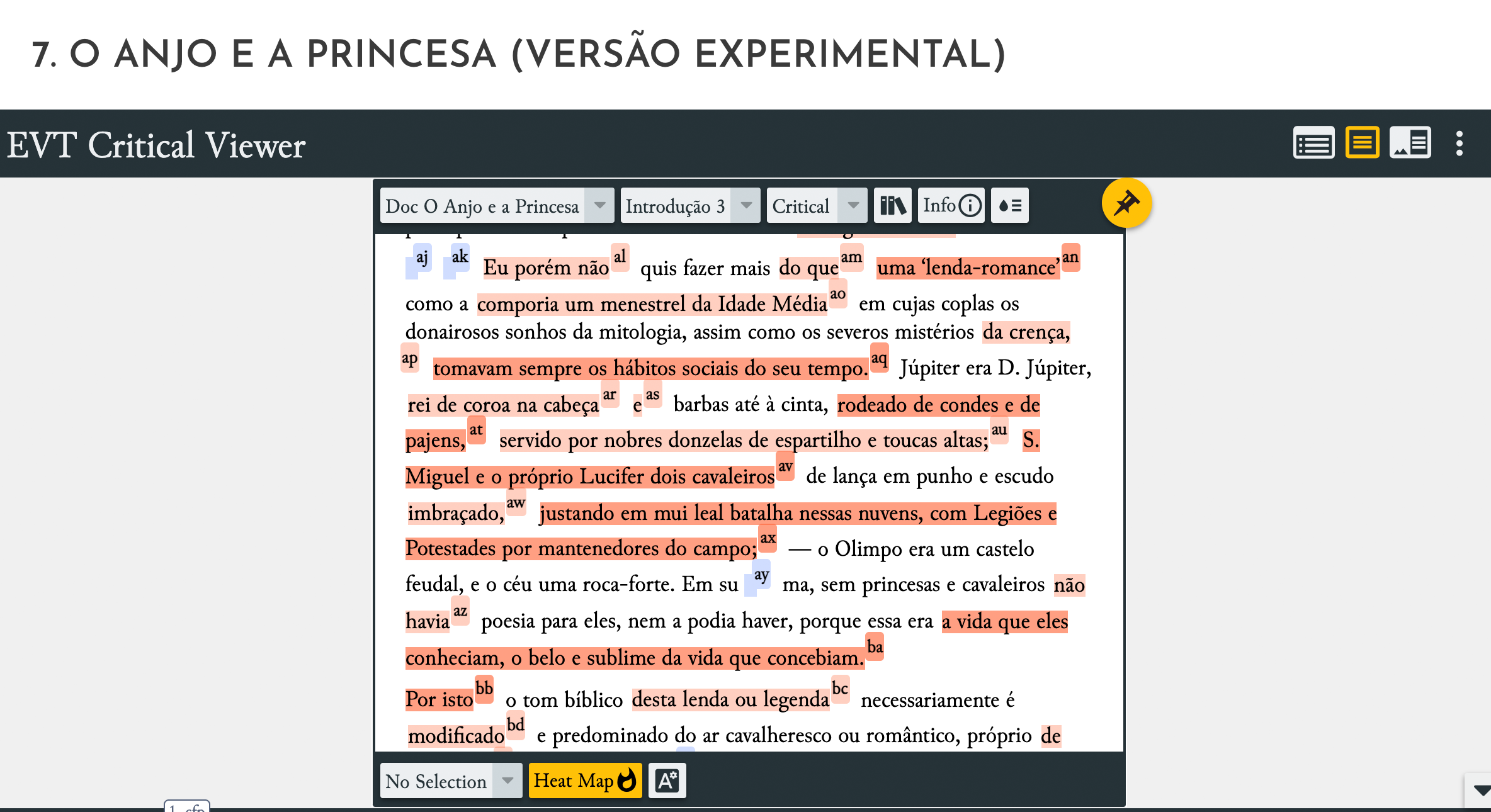

The fact that the marking tasks began with the corpus belonging to Book I from 1843/53 is based on the fact that the philological work with these texts had already been in an advanced stage. In turn, there is no doubt that these texts from 1843/53 point to more complex textual traditions. So, we have decided to start our trial edition by facing these specific cases, so to check the method’s feasibility. Indeed, the first digital edited text we displayed (presented in February, 2021, was »O anjo e a princesa«, from the Book I of the Romanceiro.43

3.4. Display Issues

At the time that we were considering moving forward with the markup structure, something crucial for the digital project development still had to be solved. We might find an answer to the question: how to consider the visualization of the edition, avoiding the complex transformations that a TEI-XML document requires? There is no doubt that although the issue of data curation had already been anticipated in the moment of choosing the TEI markup, a poor display structure would spoil the whole concept of the edition. We were very aware of this, especially because we are operating with only a small working infrastructure in this project. Because of this, the team opted for an open-source visualization option instead of a custom-drawn solution, as we will see below.

Fortunately, the best solution for these problems was already given by the Italian ecdotic tradition. We refer to the Edition Visualization Technology,44 a visualization tool developed with the aim to solve these particular challenges of Textual Criticism that we have been discussing. It is:

A light-weight, open source tool specifically designed to create digital editions from XML-encoded texts, freeing the scholar from the burden of web programming and enabling the final user to browse, explore and study digital editions by means of a user-friendly interface.45

Although EVT has been specifically designed for the development of the Digital Vercelli Book (2014) edition, in its beta version, it offers, currently, two other more advanced versions: EVT 1, and, the one which better fits our goals, EVT 2. It should be noted that EVT beta and EVT 1 have been developed in order to display diplomatic editions marked with the TEI P5 standard.

In turn, EVT 2 (in its beta 2 version, currently) has been developed within another technological framework, AngularJS, thus increasing the modularity of the web application. But its goal remains:

To offer a tool that can be customized easily and does not need any intermediate XSLT transformations. The user just needs to point at the encoded file by setting its URL in a configuration file, and to open the main page: the web-edition will be automatically built upon the provided data. As the previous version, EVT 2 is a client-only tool, with no specific server required, the user will be able to deploy the web-edition immediately on the Web.46

It should be added that, from the point of view of the user, the great advantage of EVT 2 lies in the possibility of generating critical editions (previous versions did not allow it), adapted to the Parallel Segmentation Method of TEI P5, which gives place to the critical devices of the module aimed at marking critical editions. One must be aware that some of the decisions on the texts’ TEI markup are conditioned by the requirements of the EVT tool. This concerns, in particular, the compulsory use of the encoding method for critical apparatuses when comparing to other possibilities that TEI P5 offers. In any case, the benefits of EVT are still very significant and not at all disposable, considering that this tool demands very little from the philologist in technological terms.

Another key aspect that has led to choosing EVT as a visualization tool, in addition to its simplicity, lies in its pleasant visual appearance and, above all, in the range of visualization options which with it provides the user of the critical edition. These options go hand in hand with our own editorial requirements as we discussed them earlier. Let us pay attention to what EVT developers state about version 2, the one we use for the Garrettonline project.

Among the different tools offered, EVT 2 provides a straight and quick link from the critical apparatus to the textual context of a specific reading; moreover, it allows for comparing witnesses’ texts among each other or with respect to the base text of the edition (or to another specific text); finally, it offers specific tools such as filters, to select and show different textual phenomena (e.g. the person responsible for each emendation), and a heat map showing where the variants are more frequent in the textual tradition. […] In the final version, the user will be able to examine each variant in its palaeographic context if the digitized images of each manuscript are provided.47

Figure. 6: A heat map example (the Introduction prose from »O anjo e a princesa«)

Considering these features, we do not have any doubts about the accuracy of EVT 2 with regard to the textuality we want to promote in the digital edition of Almeida Garrett’s Romanceiro.

4. CODA

In short, the advantages of using digital philology devices at the service of our scholarly edition have, we hope, now become clear. Basically, we took advantage of some of the wide representational possibilities that open source tools offer to philologists today, such as EVT.

Besides fitting a truly open notion of textuality, our edition's principles rely also on an assisted philological shape. Instead of keeping non-expert users at distance, the digital philological editing as we see it holds the ability to serve a non-expert audience as much as a more demanding one, through a careful mediation of the editor himself. Philological notes featuring helpful explanations of the text, for instance, as well as hypermedia resources, fit this purpose. In this sense, we dare to call our project to be a democratic tool since it promotes literary literacy and safeguards heritage.

Figure. 7: Displaying a philological note in a critical edition level of a poem

Insofar as we see the potential of the digital for a new and rather revolutionary textual paradigm, we can only agree with Bárbara Bordalejo48 in her opinion that such a revolution in scholarly editing does not yet exist. Nevertheless, we note that the technological issues and tasks that are already being migrated into digitally renewed procedures have some interesting consequences. We have tried to situate our own contribution in this regard. Because of our optimism, we are in a position to claim that the more we move away from the printed model, the closer the revolution in textuality will be. May we, the philologists, continue to work towards this goal.

Bibliography

ALLÉS TORRENT, Susanna: »Crítica textual y edición digital o ¿dónde está la crítica en las ediciones digitales?« In: Studia Aurea 14 (2020), pp. 63–98.

BARABUCCI, Gioele a. FISCHER, Franz: »The fFormalization of Textual Criticism. Bridging the Gap Between Automated Collation and Edited Critical Texts«. In: Peter Boot et al. (eds.): Advances in Digital Scholarly Editing. Leiden 2017, pp. 47–53.

BLECUA, Alberto: Manual de Crítica Textual. Madrid 1983.

BOTO, Sandra: As Fontes do Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett. Uma proposta de »edição crítica« [PhD thesis]. Lisbon 2011.

BOTO, Sandra: »Para a história da edição do romanceiro no Algarve: protagonistas, textos, suportes e uma falsa«. In: Promontoria Monográfica História do Algarve 03. Apontamentos para a História das Culturas de Escrita: da Idade do Ferro à Era Digital (2016), pp. 313–334.

BOTO, Sandra: »A filologia digital em discussão: o caso da edição do Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett«. In: Mirian Tavares a. Sandra Boto (eds.): Digital Culture – A State of the Art. Coimbra 2018, pp. 17–34.

BOTO, Sandra: »La collatio semiautomática al servicio de la edición del Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett«. In: Josep Lluis Martos a. Natalia Mangas (eds.): Pragmática y metodologías para el estudio de la poesía medieval. Alacant 2019, pp. 115–126.

CASTRO, Ivo: »A fascinação dos espólios«. In: Leituras 5 (1999), pp. 161–166.

DEKK, Ronald Haentjens: CollateX – Software for Collating Textual Sources (version collatex-tools-1.7.1.jar), https://collatex.net/ (accessed August 31, 2021).

DI PIETRO, Clara a. DEL TURCO, Roberto Rosselli: »Edition Visualization Technology 2.0. Affordable DSE publishing, support for critical editions, and more«. In: Peter Boot et al. (eds.), Advances in Digital Scholarly Editing. Leiden 2017, pp. 275–281.

DRISCOLL, Matthew James a. PIERAZZO, Elena: »Introduction: Old Wine in New Bottles?«. In: Matthew James Driscoll a. ElenaPierazzo (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge 2016, pp. 1–15.

DUARTE, Luiz Fagundes: »Os palácios da memória«. In: Do Caos Redivivo. Ensaios de Crítica Textual sobre Fernando Pessoa. Lisbon 2018, pp. 13–22.

EDITION VISUALIZATION TECHNOLOGY (version 2), http://evt.labcd.unipi.it/# (accessed August 31, 2021).

FERRÉ, Pere: »Da fixação oitocentista à redescoberta da voz original«. In: Pere Ferré, Pedro M. Piñero a. Ana Valenciano (eds.), Miscelánea de estudios sobre el romancero. Homenaje a Giuseppe Di Stefano. Sevilla / Faro 2015, pp. 223–249.

GABLER, Hans Walter: »Foreword«. In: Matthew James Driscoll a. Elena Pierazzo (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge 2016, pp. xiii–xv.

GARRETT, Almeida: Cancioneiro de Romances, xácaras, solaus e outros vestígios da antiga poesia nacional pela maior parte conservados na tradição oral dos povos, E agora primeiramente coligidos por J. B. de Almeida Garrett [autograph]. Online. https://bit.ly/3hzFvtl (accessed August 27, 2021).

GARRETT, Almeida: Adozinda. Romance. London 1828.

GARRETT, Almeida: Romanceiro e Cancioneiro Geral. Lisbon 1843.

GARRETT, Almeida: Romanceiro. Romances Cavalherescos Antigos. 2 Vols. Lisbon 1851.

GARRETT, Almeida: Romanceiro. I. Romances da Renascença. Lisbon 1853.

GARRETTONLINE, https://www.garrettonline.romanceiro.pt/ [website] (accessed December 27, 2021).

GRÉSILLON, Almuth: »La critique génétique: origines, méthodes, théories, espaces, frontières«. In: Veredas. Revista da Associação Internacional de Lusitanistas 8 (2007), pp. 31–45.

JUXTA COMMONS, http://www.juxtasoftware.org/juxta-commons/ (accessed August 31, 2021).

LLUC-PRATS, Javier: »La edición de textos (y pre-textos) de la literatura española contemporánea«. In: Aurélie Arcocha-Scarcia, Javier Lluc-Prats a. Mari José Olaziregi (eds.): En el taller del escritor. Génesis textual y edición de textos. Bilbao 2010, pp. 111–146.

LLUC-PRATS, Javier: »El obrador del escritor y la edición filológica del texto literario contemporáneo«. In: Bénedicte Vauthier a. Jimena Gamba Corradine (eds.): Crítica genética y edición de manuscritos hispánicos contemporáneos. Aportaciones a una ‘poética de transición entre estados’. Salamanca 2012, pp. 97–112.

LUCÍA MEGÍAS, José Manuel: »La edición hipertextual: hacia la superación del incunable del hipertexto«. In: C. Castillo Martínez a. J. L. Ramírez Luengo (eds.): Lecturas y Textos en el siglo XXI. Nuevos caminos en la edición textual. Lugo 2009, pp. 11–74.

MCGANN, Jerome: A New Republic of Letters: Memory and Scholarship in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Cambridge, MA. / London 2014.

ROBINSON, Peter: »Towards a Theory of Digital Editions«. In: VARIANTS 10 (2013), pp. 105–131.

ROMANCEIRO.PT, https://arquivo.romanceiro.pt/ (accessed August 30, 2021).

ROSELLI DEL TURCO, Roberto: »The Battle We Forgot to Fight: Should We Make a Case for Digital Editions?« In: Matthew James Driscoll a. Elena Pierazzo (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge 2016, pp. 219–238.

TANGANELLI, Paolo: »Los borradores unamunianos (algunas instrucciones para el uso)«. In: Bénédicte Vauthier a. Jimena Gamba Corradine (eds.): Crítica genética y edición de manuscritos hispánicos contemporáneos. Aportaciones a una »poética de transición entre estados«. Salamanca 2012, pp. 73–96.

VALENCIANO, Ana: »Edición Crítica de Textos de Base Oral: El Romancero«. In: Salvador Rebés (ed.): Actes del Col.loqui sobre cançó tradicional. Reus, setembre 1990. Montserrat 1994, pp. 299–307.

VALENCIANO, Ana: »Crítica a la edición crítica de los romances de la tradición oral moderna«. In: Ramón Santiago, Ana Valenciano a. Silvia Iglesias (eds.): Tradiciones discursivas. Edición de textos orales y escritos. Madrid 2006, pp. 45–69.

- 1. It is worth remembering that, in Portugal, folk balladry did not reach the same editorial success as the Spanish ballads, during the 16th and 17th centuries, since it was understood as a Castilian genre. Despite this, there is strong evidence that romances were already spread among the Portuguese oral tradition at that time. The German philologist Carolina Michaëlis de Vasconcelos confirmed this assumption in the early 20th century.

- 2. The complete Romanceiro’s bibliographical references are the following: Almeida Garrett: Adozinda. Romance. London 1828; Almeida Garrett: Romanceiro e Cancioneiro Geral. Lisbon 1843; Almeida Garrett: Romanceiro. Romances Cavalherescos Antigos. 2 Vols. Lisbon 1851; Almeida Garrett: Romanceiro. I. Romances da Renascença. Lisbon 1853.

- 3. Almeida Garrett: Romanceiro. Romances Cavalherescos II, pp. XLVf.

- 4. Almeida Garrett: Cancioneiro de Romances, xácaras, solaus e outros vestígios da antiga poesia nacional pela maior parte conservados na tradição oral dos povos, E agora primeiramente coligidos por J. B. de Almeida Garrett. Online. https://bit.ly/3hzFvtl (accessed August 27, 2021).

- 5. We attempt to expand upon this discovery in Sandra Boto: As Fontes do Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett. Uma proposta de »edição crítica«. Lisbon 2011.

- 6. Garrettonline, https://www.garrettonline.romanceiro.pt/ (accessed August 27, 2021).

- 7. Cf. Paolo Tanganelli: »Los borradores unamunianos (algunas instrucciones para el uso)«. In: Bénédicte Vauthier a. Jimena Gamba Corradine (eds.): Crítica genética y edición de manuscritos hispánicos contemporáneos. Aportaciones a una »poética de transición entre estados«. Salamanca 2012, pp. 73–96.

- 8. José Manuel Lucía Megías: »La edición hipertextual: hacia la superación del incunable del hipertexto«. In: Cristina Castillo Martínez a. José Luis Ramírez Luengo (eds.): Lecturas y Textos en el siglo XXI. Nuevos caminos en la edición textual. Lugo 2009, pp. 11–74.

- 9. Ibid., p. 68. My translation.

- 10. A good example of this statement appears in the works of Ana Valenciano: »Edición crítica de textos de base oral: el romancero«. In: Salvador Rebés (ed.): Actes del Col.loqui sobre cançó tradicional. Reus, setembre 1990. Montserrat 1994, pp. 299–307; and Ana Valenciano: »Crítica a la edición crítica de los romances de la tradición oral moderna«. In: Ramón Santiago, Ana Valenciano a. Silvia Iglesias (eds.): Tradiciones discursivas. Edición de textos orales y escritos. Madrid 2006, pp. 45–69.

- 11. Sandra Boto: »Para a história da edição do romanceiro no Algarve: protagonistas, textos, suportes e uma falsa«. In: Promontoria Monográfica História do Algarve 03. Apontamentos para a História das Culturas de Escrita: da Idade do Ferro à Era Digital (2016), pp. 313–334, here p. 332. My translation.

- 12. Ibid.

- 13. Luiz Fagundes Duarte: »Os palácios da memória«. In: Do Caos Redivivo. Ensaios de Crítica Textual sobre Fernando Pessoa. Lisbon 2018, pp. 13–22, here p. 20. My translation.

- 14. Ivo Castro: »A fascinação dos espólios«. In: Leituras 5 (1999), pp. 161–166, here p.°165. My translation.

- 15. Jerome McGann: A New Republic of Letters: Memory and Scholarship in the Age of Digital Reproduction. Cambridge / MA. / London 2014, p.°41.

- 16. Cf. Sandra Boto: »A filologia digital em discussão: o caso da edição do Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett«. In: Mirian Tavares a. Sandra Boto (eds.): Digital Culture – A State of the Art. Coimbra 2018, pp. 17–34.

- 17. We will come back to this topic later. Cf. Pere Ferré: »Da fixação oitocentista à redescoberta da voz original«. In: Pere Ferré, Pedro M. Piñero a. Ana Valenciano (eds.), Miscelánea de estudios sobre el romancero. Homenaje a Giuseppe Di Stefano. Sevilla/Faro 2015, pp. 223–249.

- 18. Peter Robinson: »Towards a Theory of Digital Editions«. In: VARIANTS 10 (2013), pp. 105–131, here p. 123.

- 19. Cf. Romanceiro.pt, https://arquivo.romanceiro.pt/ (accessed August 30, 2021).

- 20. We plan to develop this subject in a future study.

- 21. To deepen on concepts like these, please cf. Paolo Tanganelli: »Los borradores unamunianos (algunas instrucciones para el uso)«, pp. 81–84.

- 22. Javier Lluc-Prats: »El obrador del escritor y la edición filológica del texto literario contemporáneo«. In: Béndicte Vauthier a. Jimena Gamba Corradine (eds.): Crítica genética y edición de manuscritos hispánicos contemporáneos. Aportaciones a una ‘poética de transición entre estados’. Salamanca 2012, pp. 97–112, here p.°104. My translation.

- 23. Javier Lluc-Prats: »La edición de textos (y pre-textos) de la literatura española contemporánea«. In: Aurélie Arcocha-Scarcia, Javier Lluc-Prats a. Mari José Olaziregi (eds.): En el taller del escritor. Génesis textual y edición de textos. Bilbao 2010, pp. 111–146., here p. 126. My translation.

- 24. Matthew James Driscoll a. Elena Pierazzo: »Introduction: Old Wine in New Bottles?«. In: Matthew James Driscoll a. Elena Pierazzo (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge / MA 2016, pp. 1–15, here p. 9.

- 25. Ibid., p. 10.

- 26. Hans Walter Gabler: »Foreword«. In: Matthew James Driscoll a. Elena Pierazzo (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge / MA 2016, pp. xiii–xv, here p. xiv.

- 27. Likewise, the ›Home‹ page gives access to different online resources that are in some way related to the work in progress, whether they are videos, bibliography or even other media. Two other columns, ›Highlights‹ and ›News‹, draw attention to the project’s agenda.

- 28. Roberto Rosselli Del Turco: »The Battle We Forgot to Fight: Should We Make a Case for Digital Editions?« In: Matthew James Driscoll a. Elena Pierazzo (eds.): Digital Scholarly Editing. Theories and Practices. Cambridge / MA 2016, pp. 219–238, here p. 228.

- 29. Ibid., p. 227.

- 30. For instance, Gioele Barabucci a. Franz Fischer have already dedicated a discussion to this in their chapter »The Formalization of Textual Criticism. Bridging the Gap Between Automated Collation and Edited Critical Texts«. In: Peter Boot et al. (eds.): Advances in Digital Scholarly Editing. Leiden 2017, pp. 47–53, as well as Rosselli Del Turco himself has warned it very clearly, »The Battle We Forgot to Fight«, pp. 219–238.

- 31. Sandra Boto: »La collatio semiautomática al servicio de la edición del Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett«. In: Josep Lluis Martos a. Natalia Mangas (eds.): Pragmática y metodologías para el estudio de la poesía medieval. Alacant 2019, pp. 115–126, here p. 125. My translation.

- 32. Cf. Boto: »A filologia digital em discussão«.

- 33. We collected them in Boto: As Fontes do Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett.

- 34. Alberto Blecua: Manual de Crítica Textual. Madrid 1983, p. 43. My translation.

- 35. Cf. Sandra Boto: »La collatio semiautomática «.

- 36. Ronald Haentjens Dekk: CollateX – Software for Collating Textual Sources (version collatex-tools-1.7.1.jar), https://collatex.net/ (accessed August 31, 2021).

- 37. Juxta Commons, http://www.juxtasoftware.org/juxta-commons/ (accessed August 31, 2021).

- 38. Hosted at Romanceiro.pt environment website.

- 39. Be that as it may, and although this work is well documented, it should be clarified that we have not systematized it from the digital point of view yet, although we proposed it in the past. We have simply moved it to a future stage of the project. Thus, we do not discuss it in the current contribution.

- 40. Towards the definition of a dossier génétique, please cf. Almuth Grésillon: »La critique génétique: origines, méthodes, théories, espaces, frontières«. In: Veredas. Revista da Associação Internacional de Lusitanistas 8 (2007), pp. 31–45.

- 41. Cf. Boto: As Fontes do Romanceiro de Almeida Garrett.

- 42. Cf. Ibid.

- 43. »The Angel and the Princess« (my translation). João Baptista da Silva Leitão de Almeida Garrett. Garrettonline: »O Anjo e a Princesa«. Published by Garrettonline project. <https://garrettonline.romanceiro.pt/_romances/livro-i/7-o-anjo-e-a-princesa/#/imgTxt?d=doc_1&p=cfp_capa_1&s=FR&e=critical> (accessed December 27, 2021).

- 44. Edition Visualization Technology (version 2), http://evt.labcd.unipi.it/# (accessed August 31, 2021).

- 45. Cf. ibid.

- 46. Clara Di Pietro a. Roberto Rosselli Del Turco: »Edition Visualization Technology 2.0. Affordable DSE Publishing, Support for Critical Editions, and More«. In: Peter Boot et al. (eds.), Advances in Digital Scholarly Editing. Leiden 2017, pp. 275–281, here p. 277.

- 47. Ibid., p. 280.

- 48. Apud Susanna Allés Torrent: »Crítica textual y edición digital o ¿dónde está la crítica en las ediciones digitales?« In: Studia Aurea 14 (2020), pp. 63–98, here p. 92.

Add comment