Digital Journal for Philology

Of Outer and Inner Gatekeepers

In the early 21st century, intersectional theory has gained considerable importance in academia. The idea of overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, however, is much older than its recent upturn might suggest. Some scholars1 trace the historical roots of intersectionality back to the 19th century, when activists like Sojourner Truth or Anna J. Cooper began to draw attention to the difficult position of women of color, »confronted by both a woman question and a race problem.«2 A century later, Black women and lesbians claimed that they did not feel adequately addressed by either White middle class feminism of the second women’s movement or by the Civil Rights Movement which prioritized the fight against racism over the fight against gender equality.3 Despite the sociopolitical relevance of these issues of multiple forms of oppression,4 it took another decade until they found their way into academia, where they started to be addressed under the term intersectionality, coined by civil rights advocate and law professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989.5 By now, intersectionality is discussed in various disciplines and is often used in inter-/transdisciplinary research. It is either regarded as a theory, a perspective, or a methodological framework. Given its inconsistent and ambiguous use, Patricia Hill Collins’s and Sirma Bilge’s working definition of intersectionality as »a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experiences«, which is not shaped »by a single axis of social division, be it race or gender or class, but by many axes that work together and influence each other«6, probably represents the broadest possible consensus achievable on a more general level. Hill Collins and Valerie Chepp, moreover, emphasize intersectionality’s ability »to catalyze new questions and areas of investigation within existing academic disciplines.« 7 Regarding the humanities, particularly language and literary studies, Valerie Smith’s suggestion to adopt intersectionality as a reading strategy »in the service of an anti-racist and feminist politics which holds that the power relations that dominate others are complicit in the subordination of black and other women of color as well« is of great relevance.8 Literature is a powerful medium to inscribe on and (re-)produce the »dynamics and relations« that Smith writes about.9 Therefore, it is not surprising that narratology has expressed interest in an intersectional approach.10 However, Euro- and androcentric presuppositions in literary studies are also an issue on a more structural level. After all, experiences of multiple forms of discrimination not only affect characters in narratives but also their creators, whose position in the literary field may well depend on a combination of factors such as their gender assigned at birth, their place of origin, the color of their skin, their religion, or their age. As Hill Collins and Chepp argue, the attractiveness and influence of intersectionality often stems from an »epistemological recognition that a field’s dominant assumptions and paradigms are produced within a context of power relations, where white, middle-class, heterosexual, male, able-bodied experiences are taken as the (invisible) norm.«11 Hence, during the past few decades, feminist, queer, and postcolonial literary critics and activists demonstrated that neither the literary market nor literary studies are free of class, ethnic, gender, national, racial, and other prejudices. This attendance to the problem of recognition helped to clarify and address the structures that render invisible people who deviate from the White, male, middle-class, heterosexual, etc. norm. Within literary studies, one would assume a special affinity for intersectionality in the discipline of comparative literature whose scholars traditionally move between a number of philological as well as cultural areas and thus call the suspenseful field of (in)commensurabilities their very own territory. Accordingly, the relative unpopularity of intersectional theory within comparative literature, and especially within its rapidly advancing field of world literary studies, is somewhat difficult to comprehend. In times of an ever-increasing transnational connectedness, world literature has proven to be a particularly controversial concept, raising lively debates on the question of »why (not) compare,« which is, ultimately, a question of power.12 Some researchers even proclaim a new world literature, which is supposed to differ from the old canonical concept and its reputation of largely being »a white male affair.«13 Accordingly, Whiteness respectively race/ethnicity14 and gender stand out as world literature’s central markers of inequality.

Based on a number of influential agents in the literary market, or what I call the outer gatekeepers – literary prizes, critics, and publishers – who also (re-)produce certain mindsets, which I refer to as inner gatekeepers,15 I am going to explore to what extent Euro- and androcentrism are still present in current world literature debates. In other words: If White men dominated old world literature, is new world literature by implication a Black female affair?

The Underrepresentation of Women of Color within New World Literature

In its most general definition, new world literature refers to recent discourses on world literature as opposed to older ones. A pragmatic approach to gain an overview of what is commonly understood by world literature today, in the so-called digital age of (semi-)global English, would be to resort to Google.16 Due to algorithms and the resulting information bubble, the search results will vary, depending on who is looking for what and where from they are looking. Nonetheless, Wikipedia indisputably is a top search result on Google for several thousand keywords,17 including world literature, which is defined as follows:

World literature is sometimes used to refer to the sum total of the world’s national literatures, but usually it refers to the circulation of works into the wider world beyond their country of origin. Often used in the past primarily for masterpieces of Western European literature, world literature today is increasingly seen in global context.18

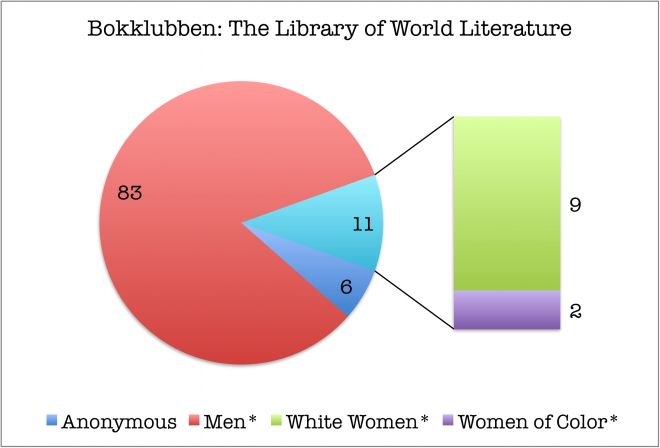

Even if this definition does not explicitly operate under the label new world literature, it clearly distinguishes today's understanding of world literature (global circulation) from an older one (Western European masterpieces) and can, therefore, be situated within new discourses on world literature. Similar records are to be found on the top-ranked websites of more reputable players in the literary field as, for example, World Literature Today (WLT), the University of Oklahoma’s bimonthly magazine of international literature and culture, or Harvard’s Institute for World Literature (IWL). In addition to these search results that comply with the widely acknowledged academic definitions of world literature as »a problem«19 or »a network«20 of »literature that circulates outside the geographic region in which it was produced,«21,further top-ranked websites such as Top 100 Works in World Literature, Masterpieces of World Literature, and Top 100 World Literature Titles indicate that it would be both premature and incorrect to situate a more traditional understanding of world literature as a Western and predominately male canon exclusively in the past. The prevalence of world literature rankings rather intimates an on-going disparity of the literatures of the world. The highest-ranked list on Google was compiled by the Norwegian Book Club (Bokklubben) who in 2002, together with the Norwegian Nobel Institute, »polled a panel of 100 authors from 54 countries on what they considered the ›best and most central works in world literature‹.«22 Only 11 of the 100 titles selected for this Library of World Literature were written by women, two of them – Japanese poet of the Heian period Shikibu Murasaki and African-American Nobel Prize laureate 1993 Toni Morrison – women of color23 (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Bokklubben: The Library of World Literature

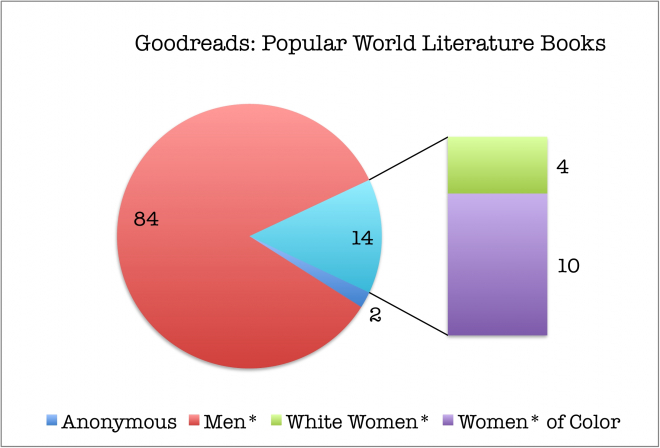

Drawing on less elitist and more democratic compilations of world literature like the world’s largest social reading platform Goodreads, a similar, albeit slightly more optimistic picture emerges. Even though the users who tag and rate the titles include significantly more contemporary writers and bestsellers in their top-hundred (out of over 1000) popular world literature books, only 14 were written by women. Of those, ten are women of color (see fig. 2): Arundhati Roy (India), Isabel Allende (Chile), Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Nigeria) who is represented with three titles, Marjane Satrapi (Iran), Laura Esquivel (Mexico), Han Kang (South Korea), and Azar Nafisi (Iran).24

Fig.2: Goodreads: Popular World Literature Books

The two lists, each created very differently, can be considered symptomatic of the position of female writers of color within the world literary canon. If a short list (100 books or less) of the best and/or most popular books of all times is composed, this inevitably results in a predominantly White and male canon as it replicates widespread (neo-)colonial, racist, and patriarchal practices. Subjected to multiple oppressions, only a few female writers of color were able to gain wider recognition before the second half of the 20th century – even if they lived and published in ›the West‹ and wrote in a former colonial language. The world literary canon remains »one and unequal«25, even though it has diversified over the past half-century – especially due to the efforts of postcolonial, anti-racist, and feminist activists and theorists. According to Franco Moretti, the academic practice of close reading, which »necessarily depends on an extremely small canon,«26 is to be held responsible for the inequality that prevails within world literature. There have been several attempts to decolonize and diversify this canon, known as new world literature.

A ›White Affair‹ no more

Alan Hill was probably the first to use the term new world literature programmatically in his article Thirty Years of a New World Literature (1993), namely for the Heinemann African Writers Series (AWS), which started in 1962 with the republication of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958). Although Heinemann’s crucial role in enabling access to a large number of post-independence African authors is by no means to be underestimated, Venkat Mani draws attention to the fact that »the sudden emergence of an African ›masterpiece‹ as late as the 1950s – and in English, the language of the colonizer – today seems dubious.«27 Furthermore, the series’ initial focus on books from West Africa (38,7%) and on books by male authors (84.7%) is apparent.28 The publisher of the AWS, James Currey, claimed that the gender imbalance »was not for want of looking.«29 In accordance with that statement, some scholars trace the paucity of publications by African women in the second half of the 20th century back »to broad societal factors, including women’s lack of privacy in the home, inequalities in both education and access to technology, and the lack of writing support,«30 whereas others blame the »gender bias among literary critics.«31

Since this rather singular use of new world literature as a designation for the English-language publications of African writers, scholars have undertaken further efforts to consolidate the term. In Global playing in der Literatur: Ein Versuch über die neue Weltliteratur (2007), Elke Sturm-Trigonakis strives to provide a systematic approach to new world literature, which she describes as »an expression of two-dimensionality«, referring »to the historicity of the construction« and the »phenomena of contemporary globalization.«32 Hence, Sturm-Trigonakis introduces this new world literature not merely to distinguish it from the old one, which to a great extent had been composed of national canons, but also as a more appropriate successor to text categories like ›minority literature‹, ›intercultural literature‹, or Migrantenliteratur. As its key features she names »multilingualism on the expression plane on the one hand and phenomena of globalization and regionalism on the content plane on the other.«33 Her corpus consists of works by 35 different authors – whereof 21 are known to identify as male and 14 as female – the majority of whom write in German, English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese.34

In her book Die neue Weltliteratur und ihre großen Erzähler (2014), Austrian literary critic Sigrid Löffler uses the term similarly as a label for hybrid literatures, whose authors, narrators, and characters do not belong to one nationality only. In the introduction, Löffler explains that she chose about 50 authors whom she defines as migrants and multilinguals. I counted 53, nine of whom identify as female. The majority originate from former British colonies in Africa, the Near and Middle East, Asia, and the Caribbean.35 Both the availability of the works in German translation and their literariness were requirements for the inclusion in the book. From the start Löffler excluded »global McFiction,«36 as she disparagingly labels strategically planned bestsellers.

In summary, it can be said that the focus of these new world literature discourses, which have become quite prevalent in Germany in recent years,37 is to overcome a previously dominant Eurocentrism by including authors from the global south and/or immigrants to Western countries whose works have acquired a wider, transnational recognition. Thus, the category of the author’s origin or, more specifically, their race/ethnicity is of paramount importance for their inclusion into this alternative canon. Albeit concentrating on works written in or translated into former colonial languages, the new world literature gives the impression of being more diverse than its predecessors, however, not necessarily less male-dominated.

A ›Male Affair‹ no more

In 1988, Polish literary scholar Mirosława Czarnecka described the status of female writers within world literature as follows: »The woman as author appears in the tradition of world literature (which is after all male) quantitatively as a deficit and qualitatively as an exception, which proves the rule.«38 By the 1970s, several feminist publishing houses had already been established – most notably the still operating Feminist Press (*1970) in the US and Virago Books (*1973) in the UK – in reaction to the second women’s movement in the 1960s, inserting both ›forgotten‹ and contemporary women writers into the English canon. Subsequently, alternative feminist canons like The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women (1985–2007) or The Longman Anthology of World Literature by Women (1989) attempted a critical revision of literary history on a global scale – at least theoretically. In her review of the latter, Adele King noticed that it was »much wider in scope than the 1985 Norton anthology of women’s writing, which includes only work in English.«39 But in spite of »the editors attempt to avoid a Eurocentric perspective,« as she points out, »the majority of the women are from Western and Central Europe (59), the United-States (43), the United Kingdom and Ireland (36), Australia and New Zealand (22), and Canada (21).«40 According to Jo-Ann Wallace, this supplemental character still predominates in women’s literary histories: »[J]ust as traditional literary history expanded to include a ›chapter‹ on women’s writing, so women’s literary history has expanded to include supplemental chapters on African-American, or lesbian, or post-colonial women’s writing.«41 Even though this observation cannot be dismissed altogether, editors and publishers have repeatedly made efforts to converge women’s literature with world literature in a more balanced, or at least, less supplemental way. The 3rd edition of The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women (2007), for example, significantly extended its »coverage of English-language women writers worldwide« and also »the representation of American writers of diverse racial, ethnic, and regional origins.«42 Additionally, international women-only literary prizes were founded. Among them the Women’s Prize for Fiction43 that was brought into being as a response to the all-male Booker Prize shortlist of 1991. On the prize’s website, it is described as »one of the most respected, most celebrated and most successful literary awards in the world«, which »celebrates the very best full length fiction written by women throughout the world.«44 This emphatically stressed world, however, turns out to be quite small. With the exception of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie from Nigeria, who won the prize in 2007, all laureates up to now originate from English-speaking countries of the global north (U.S., U.K., Ireland, Canada, and Australia), and only three of them – Andrea Levy (2004), Zadie Smith (2006), and Kamila Shamsie (2018) – are women of color.

Taken together, these examples suggest that feminist approaches to reinsert women writers into a world literary canon have given priority to the category of the author’s gender. Measures to ensure an increasingly global and diverse perspective – quite often within the boundaries of the English language – are generally taken only as a second step, giving the impression of a required supplement or even quota.

Not yet a ›Black Female Affair‹

Gisèle Sapiro writes that »[f]ollowing its globalization from the 1960s onward, we thus observe a feminization of the world literary canon, parallel to the inclusion of postcolonial authors.«45 Although accurate, this parallelization of gender and postcolonial identities supports my previous observation that the prevailing imbalances either within the largely White feminization or the largely male decolonization of the world literary canon have hardly been taken into account. However, World Literature Today’s issue on Women Writers Cover to Cover (2016) breaks with this type of isolationism by concentrating on the intersection of gender and origin, namely on texts by female authors and reviewers from more than 15 countries. The managing editor, Michelle Johnson, claims that they »briefly considered creating such an issue without comment – as if WLT existed in a utopia of parity where all writers in a literary magazine might just happen to be women.«46 Nevertheless, the editorial team decided to address these issues directly in the end. Accordingly, writer and translator Alison Anderson, in her introductory essay Of Gatekeepers and Bedtime Stories, discusses the following questions:

Why were there not more books by women in translation? What, or who, was acting as a barrier to their access to the global and, particularly, English-language market? Did women in other countries simply write less – were they the victims of patriarchal attitudes, did they have other more pressing issues to deal with? Or were they, figuratively speaking, stopped at the border – their visas not in order, the quota for immigrants already met?47

Considering the place of publication, Anderson probably means outside the United States or the Anglophone world, when she hints at gender inequality in »other countries«. While there are certainly several non-Anglophone countries where the majority of women do not even have the possibility to write or publish (for example those 44 countries where more than 20% of women are still illiterate48), it is worth mentioning that the United States does not perform particularly well either with regard to gender equality. Ranking 51 out of 149 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index, the United States lags behind several African, Asian, Central and South American states of the so-called global south.49 However, with a market share of more than 50% of all translated books,50 the dominance of Anglophone literature on the global literary market is evident. Equally evident is the power of Anglophone countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, to either hinder or trigger the global circulation of »books by women in translation«, »women in other countries«, and »immigrants«.51

Outer Gatekeepers and the Well-Guarded Borders of the Literary World

The U.S.-based feminist non-profit organization VIDA Women in Literary Arts is among the most effective critics of the still prevailing gender bias of the literary market.52 In 2010, VIDA-founder Amy King provided an overview of »the gender distribution of several major book awards and prominent ›best of lists‹« including 23 different sources, from Amazon – Top 100 Editors’ Picks 2009 to the Washington Post – Book World Top 10.53 Of these recommended or award-winning books, 592 were by male and 295 by female authors. Thus, women writers were recommended a little less than half as often as their male colleagues. Inspired by Ursula K. Le Guin’s talk Award and Gender (1999), VIDA simultaneously conducted a historical count of 16 major literary awards, revealing a similar imbalance of 929 male to 454 female laureates.54 These first VIDA counts accentuated two powerful gatekeepers in the literary world – prizes and critics – who are both able to ensure extensive visibility and prestige to authors. However, before a writer can attract their attention, her work has to be published in the first place. In what follows, I first elaborate on the literary prizes which constitute a visible and relatively easily quantifiable gatekeeper, before moving on to literary critics, and finally to literary publishers who are probably the most complex outer gatekeepers in terms of quantifiability.

Literary Prizes

Awarded annually by the Swedish Academy to authors »who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction,«55 the Nobel Prize in Literature undoubtedly represents the most famous and authoritative literary prize in the world. It has aroused much controversy due to its apparent privileging of older, male, European authors who write prose in English. Sigrid Löffler, however, reminds us that the prize has become more diverse over the last decades:

By awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature to Nigerian author Wole Soyinka in 1986 a global opening had been signaled. Since then, the Nobel committee increasingly understands itself as a new world literature laboratory, awarding more and more non-European and migrant authors from former colonies and, thus, helping to establish and enshrine the counter-canon of global literatures – immensely growing but at the same time highly fluctuating – in the western mind.56

Since 1986, the prize has also become more diverse with regard to gender. The proportion of women doubled from 7 to 14 out of a total of 114 Nobel Prize laureates. Nonetheless, Toni Morrison, who won the Nobel Prize in 1993, remains the only female laureate of color to this day. While some of the disparity can be attributed to underlying structural reasons such as the low representation of women of color in literature in general, it is likely that gender, racial, ethnic, and cultural bias also pervades the nominations, which largely come from professional groups dominated by White men.57 Last year’s postponement of the Nobel Literature prize due to the sexual harassment and abuse allegations surrounding Jean-Claude Arnault stimulated a long overdue public debate about sexism in the literary world, which is also partially responsible for the gender gap in literary awards.58 It is, moreover, an open secret that translation into major European languages, especially English, is often a precondition for the Nobel Prize in Literature – as for other renowned international literary prizes.59 »We’ve come a long way with the championing of world literature over the past decade, welcoming in a multiplicity of voices which have gone on to enrich us all. In the same period, however, we’ve noticed that it is markedly more difficult for women to make it into English translation,« Maureen Freely, former President of English PEN, wrote on the occasion of the founding of the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation in 2017 – one of several attempts »to address the gender imbalance in translated literature and to increase the number of international women’s voices«60 within world literature.61

Alarmingly, the gender gap in literary awards is not limited to the author’s gender but also includes the gender of narrators and characters. Having analyzed six of the most prestigious English-language literary prizes over a period of 15 years (2000–2014), Nicola Griffith found that books about women or girls rarely receive prizes – irrespective of whether or not they are authored by a man or a woman.62 So far, the Warwick Prize has been no exception. Although awarded to books by women in translation, neither the 2017 nor the 2018 winner had a female narrator or main character but instead polar bears (Yoko Tawada’s Memoirs of a Polar Bear) and an ageing male psychologist (Daša Drndić’s Belladonna).

Literary Critics

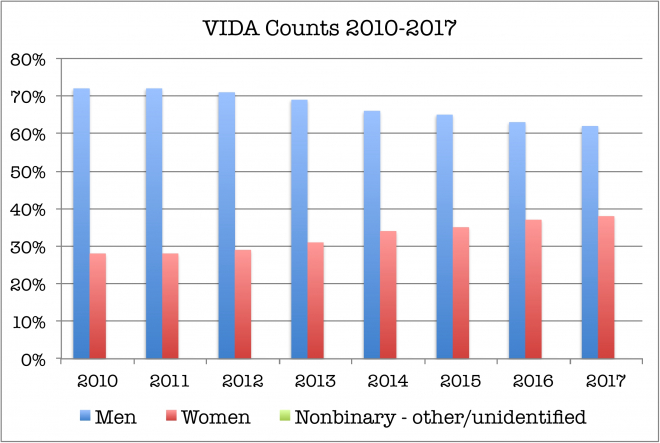

Even if books by and/or about women win prestigious awards, they may run into the danger of getting »Goldfinched.«63 Jennifer Weiner coined this term, a literary equivalent of »mansplaining« after Donna Tartt’s 2014 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Goldfinch had received belittling reviews, primarily by male critics who dismissed it »in specifically gendered terms.«64 »Goldfinching« presupposes, however, a certain, preexisting attention on the part of literary critics, which is not so easy to attract in the first place, especially not if you are a woman. Literary criticism, therefore, constitutes the second category of gatekeepers VIDA addressed in their first count and has since specialized in. Their volunteers annually »tally the gender disparity in major literary publications and book reviews« with the aim of offering »an accurate assessment of the publishing world.«65 The results of the 2010–2017 counts,66 indicate that men who mainly review books written by men are still the norm, although the situation appears to be gradually improving.67

Fig. 3: VIDA Counts 2010–2017

Inspired by previous counts in this vein, Black US-American writer and professor of English, Roxane Gay, decided to start her own count: »I wanted to see where things stood for writers of color. Race often gets lost in the gender conversation as if it’s an issue we’ll get to later.«68 Gay, with the help of her graduate assistant Philip Gallagher, tallied all reviews published in the New York Times in 2011 (742 in number), whereby she collected data on the race as well as the gender of the writers. The largest reviewed group was White male authors at approximately 59%. Women writers of color at less than 4% and transgender people at less than 1% constituted the smallest reviewed groups.69 To ensure that not only gender but also racial/ethnic identity and, in particular, the often neglected intersections between them – for instance identifying as cis- or transfemale and Black – will be taken into account in their future surveys, VIDA implemented a Women of Color Count in 2014, followed by The Year of Intersectional Thinking in 2015.70 Since then, VIDA, in addition to gender and race/ethnicity, also examines further axes of oppression experienced by authors and/or reviewers, including self-reported demographic data on age, disabilities/impairments, education, and sexual identity.71

Important as it is to confirm these disparities by facts and figures, it should also be acknowledged that diverse texts are comparatively difficult to find. Consequently, journalists, bloggers, readers, and authors started to compile and publish reading lists of books by women of color as a compensatory measure. The high demand for such recommendations – Electric Lit’s annual list of anticipated books by women and nonbinary authors of color is among their most shared pieces72 – and the rise of hashtags like #readwomenofcolo[u]r on Twitter and Instagram point to the fact that gender and racial/ethnic (among other) imbalances in reviews also reflect and reiterate previous editorial decisions. Whether a manuscript is accepted by a prestigious publisher and marketed and distributed in an effective way, strongly affects its visibility.

Literary Publishers

One of the most common justifications for the gender bias in publishing is that fewer women submit work, or that they submit manuscripts that are of lower quality and/or less marketable.73 Even if these excuses were true, they neglect the active role of editors who solicit writers and exert influence over who submits to their publications. Moreover, considering the persistence of binary gender stereotypes, it hardly seems possible that editors are able to read for the quality of the work only – just think of the pink-blue delusion encompassing almost all market sectors or the numerous studies on labor market discrimination based on gender. In 2015, author Catherine Nichols drew attention to the significant role of names in the evaluation of manuscripts. In her experiment, she sent excerpts of her novel together with a cover letter to about fifty agents, both male and female, of whom only two expressed interest. After creating a new email-address under a male pseudonym and sending the same documents to the same agents, she received 17 requests. »He is eight and a half times better than me at writing the same book,«74 writes Nichols. She adds that »[t]he judgements about my work that had seemed as solid as the walls of my house had turned out to be meaningless. My novel wasn’t the problem, it was me – Catherine.«75 As personal accounts on gender as well as racial/ethnical discrimination, such as Indian-American author Mira Jacob being expected to whitewash her story, accumulate,76 it is becoming more and more apparent that women, and especially women of color, »may ›drop out‹ rather than attempt to fight a losing battle for justice.«77

As White male publishers are not the sole »guardians of the gate«78 anymore, a ›female authors vs male publishers‹ narrative is too simplistic to explain the persisting gender bias. Several studies show that while publishing remains around 80–90 percent White, it has become a largely female domain (around 80 percent) in the Anglophone world.79 However, the predominately female staff has not yet resulted in more female writers and/or stories about women being published, reviewed, or awarded with prizes. While the conclusion that »the lack of diverse books closely correlate[s] to the lack of diverse staff« is plausible for the category of race/ethnicity – people of color and especially women of color are underrepresented at all levels: publishing staff, published authors as well as narrators and characters in books – it does not fully apply to the category of gender.80 Therefore, the alleged »tendency – conscious or unconscious – for executives, editors, marketers, sales people, and reviewers to work with, develop, and recommend books by and about people who are like them« cannot entirely explain the gender bias in publishing.81

Early Reading Experiences and the (De-)Construction of Inner Gatekeepers

The preceding examples suggest that there is a growing and also increasingly fact-based consensus on the influence of literary prizes, critics, and publishers on gender bias and the lack of diversity in the global literary market. However, in the end it all seems to come down to the question of how and why these imbalances manage to persist. In an attempt to find at least a partial answer to these questions, I would like to shift perspective from the dominant (and still important) call for more women and diversity in publishing to the responsibility of humankind to make more informed and diverse reading choices. This shift already exposes »the unconscious, invisible, inner gatekeeper«82 who declares that imbalance is a problem of the vulnerable and, therefore, best fixed by themselves, which reveals a profound ignorance towards the tenaciousness of power relations. James Baldwin once referred to this unconscious gatekeeper as the »little white man deep inside of all of us.«83 In her essay in World Literature Today, Alison Anderson responds to the gender aspect of this issue with the following hypothesis:

My own deep, and somewhat hopeless, conviction is that an unconscious reluctance to read or publish women authors goes all the way back to childhood, to the bedtime stories our parents read us, to the texts assigned in schools. To the perception that it is infinitely uncool for a little boy to be caught reading Little Women, but Tom Sawyer is okay, for both girls and boys.84

Children’s literature provides conceptions of the world, containing notions of gender, race/ethnicity, sexuality, class, etc., that are characterized by the social consensus of their respective age and culture. However, it can act not only as a mirror but also as a window on the world, giving children »a chance to learn about someone else’s life.«85 A third metaphor of children’s books as doors to the world further »signifies action, the possibility of critical engagement with texts through questioning and comparison of words, images, storylines, and other textual elements.«86 Despite a broad consensus that children’s literature should try to convey an adequate portrait of our diverse and increasingly globalized world, all too often children learn to equate a person’s gender and/or race/ethnicity with their career and income level in a discriminatory manner through their early reading experiences. This contributes to the construction of inner gatekeepers – mindsets or potentially identity-forming stereotypes – early in a child’s development, which involves outer gatekeepers, both on a personal (parents) and on a structural level (publishers, school curricula).

Gender Parity and Diversity in Children’s Books

Studies like the renowned PISA assessment show that in all OECD countries girls are ahead of boys in reading on average and are more likely to read for pleasure. However, »the size of the gender gap varies considerably across countries, suggesting that boys and girls do not have inherently different interests and academic strengths, but that these are mostly acquired and socially induced.«87 These results indicate that reading is still perceived as a more female activity in many countries and, therefore, particularly encouraged among girls. However, female characters have been severely underrepresented in children’s books for a long time, urging girls to identify with male characters.88 In the 1960s and 70s, feminists started to criticize this disparity and the prevailing gender stereotypes in children’s books as being jointly responsible for the reproduction of a patriarchal system. Since several studies were able to confirm these accusations,89 UNESCO urged »[g]overnments to take all necessary measures to eliminate stereotypes on the basis of sex from educational materials at all levels.«90 Janice McCabe et al. found that children’s books published at the end of the 20th century come quite close to parity in the United States – the number-one children’s book market in the world.91 The conventional children’s literature canon, however, largely consists of older works and, therefore, remains overly male.

With regard to ethnical/racial and cultural diversity, initiatives such as We Need Diverse Books have shown some effects.92 The Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University of Wisconsin recorded an increase in children’s books about people of color and first nations people from 13 percent in 2002 to 25 percent in 2017.93 Although this number roughly corresponds with the United States census (23.4 percent non-White citizens),94 the much lower percentage of books written by people of color (15 percent in 2017) indicates a more persistent imbalance in authorship.95 However, global children’s literature comprises not only »multicultural literature« and »books by and about communities of color within the United States,« but also »international books produced by authors/illustrators and publishers outside the United States.«96 It is not particularly surprising that the latter come from just a few countries and account for »a remarkably small portion« (an estimated 5%) of the literature available to American children as it reflects the situation of world literature in general.97 Furthermore, in their study on illustrated children’s books published in France in 1994, Carole Brugeilles et al. found that there is a tendency among internationally-circulating children’s books to »simplify all historical, geographical, cultural and social markers«, and, therefore, to »say remarkably little about the diversity of the world.«98 In their sample, the eradication of diversity seemed to be a prerequisite for children’s literature crossing national borders either in translation or in the original language, leaving diversity to those who can afford – in general large and monolingual book markets such as the United States.

The Intersection of Gender and Race/Ethnicity

As with world literature discourses, the intersection of gender and race/ethnicity has rarely been discussed or problematized with regard to children’s literature. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis usually concentrate on either gender or ethnical/racial disparity, neglecting the even more blatant underrepresentation of female authors, narrators, and characters of color. In recent years, however, there has been a strong upturn in children’s books featuring diverse and inspirational female characters, such as Elena Favilli and Francesca Cavallo’s Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls (2016) or Kate Pankhurst’s Fantastically Great Women Who Changed the World (2016). Pankhurst reads the success of this »new kind of bedtime story« as a response to the »regressive attitude to women and to diversity« mediated through the news on a regular basis.99 Consequently, as Favilli puts it, the books are meant to fill a vacuum »in a time when gender stereotyping, and equal rights, and empowering young girls is very important and is happening internationally.«100 The fact that Good Night Stories is considered »the most funded original book in the history of crowdfunding« so far, illustrates the high level of public interest.101 The authors raised more than 1 million U.S. dollars on Kickstarter and were supported by donors from over 70 countries.102 Artists from 22 different countries were involved in the illustration of the 100 characters described in the book, 40 percent of whom are women of color. The stories cover different time periods – from Pharaoh Hatshepsut (ca. 1508–1458 B.C.) to Coy Mathis (born ca. 2007) as well as 43 nationalities103 and about 70 professions. With more than half a million copies sold, translations into 30 different languages, and a very popular sequel, Good Night Stories is certainly a worldly, feminist, and highly successfully bedtime story.

Ironically, children’s books about inspirational girls and women were criticized for their exclusion of boys. For this reason, some schools declined offers to read from books with female lead characters, or they permitted only girls to attend such readings. So, while »girls are expected to read books about boys, and people of color are expected to read books about whites (and boys),« it clearly does not seem to work the other way round.104 Here the metaphor of children’s books as doors to the world comes in. Living up to the metaphor in its name, the partnership of educators supporting the use of global children’s literature in schools Doors to the World stresses the great responsibility of teachers in selecting appropriate reading material »for particular classrooms that serve particular cultural communities.«105 In recent years, 11-year-old Marley Dias’s claim that her teachers did not just fail in serving her particular – Black – community but, more specifically, her as a Black girl went viral. Dias could not relate to »the books about white boys and their dogs« that she was supposed to read at school, which is probably the most important gatekeeper at this stage of life.106 Accordingly, in November 2015, Dias launched the #1000blackgirlbooks campaign with the aim to collect 1,000 children’s books that feature Black girls as their main characters. Dias has far exceeded her original goal, with some of the over 11,000 collected books having been catalogued into a readily accessible database appropriate for youth, parents, educators, schools, and libraries.107

Such attempts at diversifying children’s bedtime and school reading might not directly lead to adults feeling more comfortable reading or assigning stories with diverse female characters to boys, but they are at least able to raise awareness that neither parents nor teachers should feel too comfortable with all-White and/or all-male reading lists either. In doing so, I argue, they contribute to the deconstruction of inner gatekeepers, namely gendered and ethnically marked expectations in children’s reading, and, can potentially also prevent the construction of some outer gatekeepers like predominantly White and male bedtime stories or reading lists at schools.

Conclusion and Outlook

In conclusion, I would like to return to the initial question of whether Euro- and androcentrism are still present in current (new) world literature debates. Despite the tendency to open up and diversify world literature discourses, a strong need to canonize persists, represented by lists of the best and/or most popular books of all times, within which women and especially women of color are severely underrepresented. This also applies to certain attempts at introducing new world literature as a generic name for a globally circulating inter- or rather transnational literature. As the primary concern of these endeavors is to overcome a previously dominant Eurocentrism, the category of the author’s race/ethnicity rather than their gender is of paramount importance. Whereas world literature’s Whiteness has certainly been revised, its androcentrism has to some extent been perpetuated by the discourse of new world literature. Nevertheless, efforts both within the literary market and within academia like the establishment of women’s presses, women-only literary prizes, and supposedly global female literary histories were able to raise gender awareness. While new world literature and women’s literature discourses only partially intersect – the former focusing on the author’s race/ethnicity, the latter on the author’s gender – World Literature Today with its issue on female writers succeeded in drawing attention to precisely this intersection. Following up on the question of where the women in world literature were, which Alison Anderson had raised in her introductory essay, I looked into several outer gatekeepers of the literary market. Although women of color are still underrepresented on the level of literary awards, criticism, and publishing, a heightened intersectional awareness can be observed. Several projects, many of them deriving from digital literary activism and pointing to the outer gatekeeper’s reproduction of gender and racial/ethnical biases, have not just polarized opinion but also achieved some initial successes. Anderson, however, emphasizes the fact that a much more long-term process is the visualization and elimination of so-called inner gatekeepers – unconscious mindsets and stereotypes that are transferred primarily through reading socialization.108

Accordingly, I would like to suggest two practical measures to visualize and eliminate inner gatekeepers that could be implemented in academia. First, it would be important to teach intersectionality on a theoretical level and to give diverse women’s and children’s literature a more prominent role as research objects within discussions on world literature. As long as world literature’s default mode is male writers and a highly educated adult reading public, literature by and about women – especially women of color – as well as literature for children – especially literature not featuring White boys – will inevitably remain under-researched within world literature studies. Similarly to the one of publishers, editors, and reviewers, the aesthetic credo of literary scholars – that ›the quality‹ of the writing counts above all else – all too often resembles a self-fulfilling prophecy: The paucity of scholars who dare to research and teach subjects such as global women’s writing and children’s literature that are generally considered negligible (and, therefore, poorly-funded), is taken as proof of their lack of quality. This alleged lack of quality, which is a highly subjective and constructed category, is then again, rather conveniently, used to justify the underrepresentation of books by and/or about girls and women of color in a field like world literature. However, simply including more of the supposedly best and/or most visible books without seriously questioning why precisely these books are successful, cannot do justice to the kind of inclusive approach to world literature that large parts of academia pride themselves for.

Including an intersectional understanding of world literature in teacher training programs would constitute another fundamental step in achieving »some sort of psychological, emotional parity«.109 School reading provides a crucial platform to either (re-)produce or deconstruct inner gatekeepers and, subsequently, diversify certain mindsets that may otherwise persist into adulthood. So long as language and literary studies at colleges and universities, where teachers eventually receive their training, are dominated by the supposedly ›best‹ works of an overly White, male, and usually monolingual literary canon, children’s reading socialization will likely continue to be determined by distorted mirrors and opaque windows on the world. Neither does it contribute to a feminization and decolonization of curricula if these nationally oriented study programs regard new world literatures as an academic extravaganza belonging solely to fields such as comparative literature and postcolonial studies. If prospective teachers are continuously confronted with ethnically/racially, culturally, and gender-biased syllabi, it is likely that they will keep the doors to the world shut rather than open in their own teaching practice.

However, the lively ›decolonize the curriculum‹ debate that has been going on in the United Kingdom for some time now, allows me to conclude on a more optimistic note.110 It looks as if the repeated calls by students to decolonize their curricula are beginning to bear fruit; several universities have already initiated diversification measures.111 Moreover, this debate might be able to stimulate an even broader discussion about the great and rather delicate responsibility of educational institutions to constantly renegotiate which traditions need to be thoroughly revised, if not completely abandoned.

Works Cited

ANDERSON, Alison: »Of Gatekeepers and Bedtime Stories: The Ongoing Struggle to Make Women’s Voices Heard«. In: World Literature Today 90.6 (2016), pp. 12–15.

ARIKIN, Marian and Barbara Shollar (eds.): The Longman Anthology of World Literature by Women: 1875–1975. New York 1989.

BACH, Lisa: »Von den Gender Studies in die Literaturwissenschaft: Intersektionalität als Analyseinstrument für narrative Texte«. In: Laura Muth and Annette Simonis (eds.): Gender-Dialoge. Gender-Aspekte in den Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften. Berlin 2015, pp. 11–30.

BANDA-AAKU, Ellen: »Playing Catch-Up«. In: Journal of Southern African Studies 40.3 (2014), pp. 607–613.

BOOKCAREERS.COM: »Salary Survey Results 2017«. https://www.bookcareers.com/salary-survey-2/bookcareers-com-salary-survey-results-2017/ (last viewed 12.01.2019).

BOTELHO, Maria José and Natalie Sowell: »Teaching Global Children’s Literature: What to Read and How to Read«. In: Global Learning (Education Week Blog) (09.08.2016). https://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/global_learning/2016/08/teaching_global_childrens_literature_what_to_read_and_how_to_read.html (last viewed on 12.01.2019).

BRUGEILLES, Carole, Isabelle Cromer, Sylvie Cromer: »Male and Female Characters in Illustrated Children’s Books or How children’s literature contributes to the construction of gender«. Transl. from the French by Zoe Andreyev. In: Population (English Edition) 57.2 (2002), pp. 237–267.

CAMBRIDGEFLY: »Decolonising the English Faculty: An Open Letter«. In: FLY.blog (14.06.2017). https://flygirlsofcambridge.com/2017/06/14/decolonising-the-english-faculty-an-open-letter/ (last viewed on 16.02.2019).

COMBAHEE RIVER COLLECTIVE: »A Black Feminist Statement«. In: Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (eds.): This Bridge Called my Back. Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York 1981, pp. 210–218.

COOPER, Anna Julia: A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South. New York 1988 [1892].

COOPERATIVE CHILDREN'S BOOK CENTER (CCBC): »Publishing Statistics on Children’s Books about People of Color and First/Native Nations and by People of Color and First/Native Nations Authors and Illustrators (last updated: 22.02.2018)«. https://ccbc.education.wisc.edu/books/pcstats.asp (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

COPE, Sam Silverwood: »Wikpedia: Page One of Google UK for 99% of Searches«. In: Pi Datametrics News and Blog (08.02.2012). https://www.pi-datametrics.com/wikipedia-page-one-of-Google-uk-for-99-of-searches/ (last viewed on 17.02.2019).

COSER, Lewis A.: »Publishers as Gatekeepers of Ideas«. In: The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 421 (1975), pp. 14–22.

CRENSHAW, Kimberlé: »Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics«. In: The University of Chicago Legal Forum 140 (1989), pp. 139–167.

CURREY, James: Africa Writes Back. The African Writers Series & The Launch of African Literature. Oxford a.o. 2008.

CZARNECKA, Mirosława: Frauenliteratur der 70er und 80er Jahre in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Wrocław 1988.

DAMROSCH, David: What Is World Literature? Princeton 2003.

DAVIS, Caroline: »A Question of Power: Bessie Head and her Publishers«. In: Journal of Southern African Studies 44.3 (2018), pp. 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2018.1445354.

DIAS, Marley: Marley Dias Gets It Done: And So Can You! New York 2018.

DYER, Richard: White. London/New York 2008 [1997].

EPSTEIN, B. J.: »Why Children’s Books that Teach Diversity are more Important than ever«. In: The Conversation. Academic Rigour, Journalistic Flair (06.02.2017). http://theconversation.com/why-childrens-books-that-teach-diversity-are-more-important-than-ever-72146 (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

FAVILLI, Elena and Francesca Cavallo: »Preface«. In: Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls: 100 Tales of Extraordinary Women. UK a.o. 2017, pp. xi–xii.

FLOOD, Alison: »Read Like a Girl: How Children’s Books of Female Stories Are Booming«. In: The Guardian (11.08.2017). https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/aug/11/read-like-a-girl-how-childrens-books-of-female-stories-are-booming (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

FRAUENZÄHLEN: »Pilotstudie ›Sichtbarkeit von Frauen in Medien und im Literaturbetrieb‹«. http://www.frauenzählen.de/studientext.html (last viewed on 19.03.2019).

FRIEDMAN, Susan Stanford: »Why Not Compare?«. In: PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 126.3 (2011), pp. 753–762.

GAY, Roxane: »Where Things Stand«. In: The Rumpus (06.06.2012). https://therumpus.net/2012/06/where-things-stand/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

GILBERT, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar (eds.): The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English. 2 vols. New York/London 2007.

GOODREADS: »Popular World Literature Books«. https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/world-literature (last viewed on 27.09.2018).

GRASSROOTS COMMUNITY FOUNDATION: »1000 Black Girl Books Resource Guide«. https://grassrootscommunityfoundation.org/1000-black-girl-books-resource-guide/#1458589376402-f27f8cc7-dd8b (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

GRIFFITH, Nicola: »Books about Women don’t Win Big Awards: Some Data«. In: Nicola Griffith (26.05.2015). https://nicolagriffith.com/2015/05/26/books-about-women-tend-not-to-win-awards/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

GUILLORY, John: Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation. Chicago 1993.

HILL, Alan: »Thirty Years of a New World Literature«. In: Bookseller 16.1 (1993), pp. 58–59.

HILL COLLINS, Patricia and Sirma Bilge: Intersectionality. Cambridge / M. 2016.

HILL COLLINS, Patricia and Valerie Chepp: »Intersectionality«. In: Georgina Waylen et al. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics. Oxford / M. 2013, pp. 57–87.

HOBY, Hermione: »Toni Morrison: ›I’m writing for black people...I don’t have to apologise‹«. In: The Guardian (25.04.2015). https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/apr/25/toni-morrison-books-interview-god-help-the-child (last viewed on 10.01.2019).

IACOVELLI, Sara u.a.: »The 2016 VIDA Count«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (17.10.2017). http://www.vidaweb.org/the-2016-vida-count/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

INDEX TRANSLATIONUM: »Evolution in time for each target language«. http://www.unesco.org/xtrans/bsstatexp.aspx?crit1C=2&crit1L=4&nTyp=min (last viewed on 06.01.2019).

INDEX TRANSLATIONUM: »Evolution in time for each original language«. http://www.unesco.org/xtrans/bsstatexp.aspx?crit1C=2&crit1L=3&nTyp=min (last viewed on 06.01.2019).

INNSBRUCKER ZEITUNGSARCHIV: »Literaturkritik in Zahlen«. https://www.uibk.ac.at/iza/literaturkritik-in-zahlen/ (last viewed on 19.03.2019).

JACOB, Mira: »I Gave a Speech about Race to the Publishing Industry and no one Heard Me«. In: BuzzFeed (17.09.2015). https://www.buzzfeed.com/mirajacob/you-will-ignore-us-at-your-own-peril (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

JAMES, Adeola: »Ama Ata Aidoo (Interview)«. In: James (ed.): In Their Own Voices. African Women Writers Talk. London/Portsmouth 1991, pp. 9–27.

JOHNSON, Michelle: »Editor’s Note«. In: World Literature Today 90.6 (2016), p. 5.

KEAN, Danuta (ed.): Writing the Future: Black and Asian Writers and Publishers in the UK Market Place (2015). https://www.spreadtheword.org.uk/writing-the-future/ (last viewed on 12.01.2019).

KING, Adele: »The Longman Anthology of World Literature by Women, 1875–1975 (Book Review)«. In: World Literature Today 63.3 (1989), p. 543.

KING, Amy: »›Best of 2009‹ and ›Historical Count‹«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (29.03.2010). http://www.vidaweb.org/best-of-2009/ (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

KING, Amy and Sarah Clark: »The 2017 VIDA Count«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (17.6.2018). https://www.vidaweb.org/the-2017-vida-count/ (last viewed on 12.01.2019).

KLEIN, Christian and Falko Schnicke (eds.): Intersektionalität und Narratologie: Methoden, Konzepte, Analysen. Trier 2014.

KWON, R. O.: »48 Books By Women and Nonbinary Authors of Color to Read in 2019«. In: Electric Lit (01.01.2019). https://electricliterature.com/48-books-by-women-and-nonbinary-authors-of-color-to-read-in-2019-d9b4fdcc53c2 (last viewed on 13.01.2019).

LE GUIN, Ursula K.: »Award and Gender«. In: The Wave in the Mind. Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. Bosten / M. 1999, pp. 141–151.

LITPROM: »Der Liberaturpreis«. https://www.litprom.de/beste-buecher/liberaturpreis/der-preis/ (last viewed on 07.01.2019).

LÖFFLER, Sigrid: Die neue Weltliteratur und ihre großen Erzähler. München 2014.

LOW, Jason T.: »Where is the Diversity in Publishing? The 2015 Diversity Baseline Survey Results«. In: The Open Book (26.01.2016). http://blog.leeandlow.com/2016/01/26/where-is-the-diversity-in-publishing-the-2015-diversity-baseline-survey-results/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

MANI, Venkat B.: »Bibliomigrancy. Book Series and the Making of World Literature«. In: Theo D’haen (ed.): The Routledge Companion to World Literature. London a.o. 2012, pp. 283–296.

MCCABE, Janice et al.: »Gender in Twentieth-Century Childrens’s Books: Patterns of Disparity in Titles and Central Characters«. In: Gender & Society 15.2 (2011), pp. 197–226.

MILLIOT, Jim: »The PW Publishing Industry Salary Survey, 2018«. In: Publishers Weekly (09.11.2018). https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/publisher-news/article/78554-the-pw-publishing-industry-salary-survey-2018.html (last viewed on 12.01.2019).

MORETTI, Franco: »Conjectures on World Literature«. In: New Left Review 1 (2000), pp. 54–68.

N.A.: »About the VIDA Count«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (21.02.2012). http://www.vidaweb.org/the-count/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

N.A.: »Neue Weltliteratur und der Globale Süden«. In: Börsenblatt (08.01.2016). https://www.boersenblatt.net/artikel-litprom_literaturtage_am_22._23._januar_im_literaturhaus_frankfurt.1077407.html (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

N.A.: »Neues Literaturprojekt im IZ: Heidelberg liest neue Weltliteratur«. In: IZ – Interkulturelles Zentrum (11.03.2016). https://iz-heidelberg.de/eroeffnung-von-heidelberg-liest-neue-weltliteratur/ (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

N.A.: »The 2014 Women of Color VIDA Count«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (06.04.2015). http://www.vidaweb.org/2014-women-of-color-vida-count-2/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

NICHOLS, Catherine: »Homme de Plume: What I Learned Sending My Novel out under a Male Name«. In: Jezebel (04.08.2015). https://jezebel.com/homme-de-plume-what-i-learned-sending-my-novel-out-und-1720637627 (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

NOEL, Aimee u.a.: »The 2015 VIDA Count«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (30.03.2016). http://www.vidaweb.org/the-2015-vida-count/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

NORTON, W.W. & Company: »The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women«. http://books.wwnorton.com/books/webad.aspx?id=11623 (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

OECD: PISA 2009 Results: Learning to Learn. Student Engagement, Strategies and Practices (Vol. III). Paris 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264083943-en.

OXFORD ENGLISH DICTIONARY: »Ethnicity, n.«. http://www.oed.com/ (last viewed on 07.10.2018).

PAUL, Caroline: »Why Boys Should Read Girl Books«. In: ideas.ted.com (29.03.2016). https://ideas.ted.com/why-boys-should-read-girl-books/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

RADHAKRISHNAN, R.: »Why Compare?«. In: Rita Felski and Susan Stanford Friedman (eds.): Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses. Baltimore 2013, pp. 15–33.

RICHEY, Debora: »Black African Women Writers: A Selective Guide«. In: Collection Building 14.1 (1995), pp. 23–31.

ROY, Jessica: »11-Year-Old ›Sick of Reading About White Boys and Dogs‹ Starts Her Own Black Girl Book Drive«. In: The Cut (22.01.2016). https://www.thecut.com/2016/01/girl-starts-1000blackgirlbooks-book-drive.html (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

SAPIRO, Gisèle: »How Do Literary Works Cross Borders (or Not)? A Sociological Approach to World Literature«. In: Journal of World Literature 1.1 (2016), pp. 81–9. https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00101009.

SMITH, Valerie: Not Just Race, Not Just Gender: Black Feminist Readings. London a.o. 1998.

SPENDER, Lynne: Intruders on the Rights of Men: Women’s Unpublished Heritage. London/Boston 1983.

STAN, Susan: »Going Global: World Literature for American Children«. In: Theory Into Practice 38.3 (1999), pp. 168–177.

STATCOUNTER GLOBALSTATS: »Search Engine Market Share Worldwide (Jan 2018–Jan 2019)«. http://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share (last viewed on 17.02.2019).

STURM-TRIGONAKIS, Elke: Global playing in der Literatur: Ein Versuch über die Neue Weltliteratur. Würzburg 2007.

STURM-TRIGONAKIS, Elke: Comparative Cultural Studies and The New Weltliteratur. Transl. from the German by Athanasia Margoni and Maria Kaiser. West Lafayette 2013.

SWAIN, Harriet: »Students want their curriculums decolonised. Are universities listening?«. In: The Guardian (30.01.2019). https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/jan/30/students-want-their-curriculums-decolonised-are-universities-listening (last viewed on 16.02.2019).

THE NOBEL PRIZE: »Alfred Nobel’s Will [1895]«. https://www.nobelprize.org/alfred-nobel/alfred-nobels-will-2/ (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

THE STELLA PRIZE: »The Count«. https://thestellaprize.com.au/the-count/ (last viewed on 19.03.2019).

THE WARWICK PRIZE FOR WOMEN IN TRANSLATION: »About the Prize«. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/womenintranslation/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

UNITED NATIONS: Report of the World Conference of the United Nations Decade For Women: Equality, Development and Peace (A/CONF. 94/35), Copenhagen, 14 to 30 July 1980. New York 1980. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/36306.

UNITED STATES CENSUS BUREAU: »Quick Facts«. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/INC110217 (last viewed on 12.01.2019).

WALKOWITZ, Rebecca L.: »Unimaginable Largeness: Kazuo Ishiguro, Translation, and the New World Literature«. In: Novel 40.3 (2007), p. 216–239.

WALLACE, Jo-Ann: »Women’s Literary History in a Minor Key«. In: Katherine Binhammer and Jeanne Wood (eds.): Women and Literary History: »For There She Was«. Newark a.o. 2003, pp. 201–219.

WASHBOURNE, Kelly: »Translation, Littérisation, and the Nobel Prize for Literature«. In: TranscUlturAl 8.1 (2016), pp. 57–75.

WE NEED DIVERSE BOOKS: »About WNDB«. https://diversebooks.org/about-wndb/ (last viewed on 12.01.2019).

WEINER, Jennifer: »If you enjoyed a good book and you’re a woman, the critics think you’re wrong«. In: The Guardian (24.11.2015). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/24/good-books-women-readers-literary-critics-sexism?CMP=edit_2221 (last viewed on 13.01.2019).

WEITZMAN, Lenore J. et al.: »Sex-Role Socialization in Picture Books for Preschool Children«. In: American Journal of Sociology 77.6 (1972), pp. 1125–1150.

WIKIPEDIA: »World Literature«. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_literature (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

WILSON, Kristian: »Jennifer Weiner’s Coined Term ›Goldfinching‹ Is The New ›Mansplaining‹ For Readers«. In: Bustle (24.11.2015). https://www.bustle.com/articles/125946-jennifer-weiners-coined-term-goldfinching-is-the-new-mansplaining-for-readers (last viewed on 13.01.2019).

WOMEN'S PRIZE FOR FICTION: »History«. In: https://www.womensprizeforfiction.co.uk/about/history (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

WORLD ECONOMIC FORUM: The Global Gender Gap Report 2018. Geneva 2018. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf.

List of Figures

Fig. 1: Bokklubben: The Library of World Literature.

BOKKLUBBEN: »100 Prominent Authors from More than 50 Different Nations Have Elected The Library of World Literature: ›The 100 Best Books in the History of Literature‹«. https://www.bokklubben.no/SamboWeb/side.do?dokId=65500 (last viewed on 27.09.2018).

Fig. 2: Goodreads: Popular World Literature Books.

GOODREADS: »Popular World Literature Books«. https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/world-literature (last viewed on 27.09.2018).

Fig. 3: VIDA Counts 2010–2017.

N.A: »VIDA Counts 2010–2017«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts. http://www.vidaweb.org (last viewed on 27.09.2018).

- 1. First and most prominently Kimberlé Crenshaw: »Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics«. In: The University of Chicago Legal Forum 140 (1989), p. 153f. and 160.

- 2. Anna Julia Cooper: A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South. New York 1988 [1892].

- 3. See, for example: Combahee River Collective: »A Black Feminist Statement«. In: Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa: This Bridge Called My Back. Writings by Radical Women of Color. New York 1981, pp. 210–218.

- 4. In this article, I use the term oppression to refer to specific systems of power, for example racial or gender oppression, which as a rule generate social inequalities.

- 5. Crenshaw: »Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex«.

- 6. Patricia Hill Collins and Sirma Bilge: Intersectionality. Cambridge / M. 2016, p. 2.

- 7. Patricia Hill Collins and Valerie Chepp: »Intersectionality«. In: Georgina Waylen et al. (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Politics. Oxford / M. 2013, p. 63.

- 8. Valerie Smith: Not Just Race, Not Just Gender: Black Feminist Readings. London a.o. 1998, p. xvi.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. See: Christian Klein and Falko Schnicke (eds.): Intersektionalität und Narratologie: Methoden, Konzepte, Analysen. Trier 2014; Lisa Bach: »Von den Gender Studies in die Literaturwissenschaft: Intersektionalität als Analyseinstrument für narrative Texte«. In: Laura Muth and Annette Simonis (eds.): Gender-Dialoge. Gender-Aspekte in den Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaften. Berlin 2015, pp. 11–30.

- 11. Hill Collins and Chepp: »Intersectionality«, p. 64–65.

- 12. R. Radhakrishnan: »Why Compare?« In: Rita Felski and Susan Stanford Friedman (eds.): Comparison: Theories, Approaches, Uses. Baltimore 2013, pp. 15–33; Susan Stanford Friedman: »Why Not Compare?« In: PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 126.3 (2011), pp. 753–762.

- 13. David Damrosch: What Is World Literature? Princeton 2003, p. 16, paraphrasing John Guillory: Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation. Chicago 1993, p. 32.

- 14. I use the terms here synonymously because in practice they overlap in many ways. As Richard Dyer (2008) emphasized with regard to Whiteness and race: »As long as race is something only applied to non-white peoples, as long as white people are not racially seen and named, they/we function as a human norm. Other people are raced, we are just people.« (p. 1) This equally applies to ethnicity, the »[s]tatus in respect of membership of a group regarded as ultimately of common descent, or having a common national or cultural tradition« (OED). White people are hardly ever described in relation to their race/ethnicity, because they »have had so very much more control over the definition of themselves and indeed of others than have those others«. See: Richard Dyer: White. London/New York 2008 [1997], p. xii.

- 15. I borrow the terminology from Alison Anderson who distinguishes »the obvious, visible traditional male gatekeeper« (for example jurors, critics, and publishers, whom I call outer gatekeepers) from »the unconscious, invisible, inner gatekeeper«. See: Alison Anderson: »Of Gatekeepers and Bedtime Stories: The Ongoing Struggle to Make Women’s Voices Heard«. In: World Literature Today 90.6 (2016), p. 13. The metaphor of the gatekeeper was previously used by Lewis A. Coser: »Publishers as Gatekeepers of Ideas«. In: The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 421 (1975), p. 15. A feminist revision of the metaphor can be found in Lynne Spender: Intruders on the Rights of Men: Women’s Unpublished Heritage. London/Boston 1983, p. 13.

- 16. With a worldwide market share of 92.86 percent as of January 2019, Google is the most used web search engine worldwide. See: Statcounter GlobalStats: »Search Engine Market Share Worldwide (Jan 2018–Jan 2019)«. http://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share (last viewed on 17.02.2019).

- 17. In 2012, a study was conducted on the (over-)representation of Wikipedia on Google. The study looked at 1,000 search terms (provided by a random noun generator) in Google UK and measured the rankings for Wikipedia. For 99% of searches (nouns), a respective Wikipedia entry appeared on the first page of Google UK. Wikipedia further held the top position for 56% and position one to five for 96% of searches on Google UK. See: Sam Silverwood Cope: »Wikipedia: Page One of Google UK for 99% of Searches«. In: Pi Datametrics News and Blog (08.02.2012). https://www.pi-datametrics.com/wikipedia-page-one-of-Google-uk-for-99-of... (last viewed on 17.02.2019).

- 18. Wikipedia: »World Literature«. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_literature (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

- 19. Franco Moretti: »Conjectures on World Literature«. In: New Left Review 1 (2000), p. 55.

- 20. Damrosch: What Is World Literature?, p. 3.

- 21. Rebecca L. Walkowitz: »Unimaginable Largeness: Kazuo Ishiguro, Translation, and the New World Literature«. In: Novel 40.3 (2007), p. 216.

- 22. Bokklubben: »100 Prominent Authors from More than 50 Different Nations Have Elected The Library of World Literature: ›The 100 Best Books in the History of Literature‹«. https://www.bokklubben.no/SamboWeb/side.do?dokId=65500 (last viewed on 27.09.2018).

- 23. I use the term woman of color – a necessarily complex and imperfect category – for a person who is known to identify as female and as non-White (which does not necessarily mean Black), or who is at least not known not to identify as female and as non-White.

- 24. Goodreads: »Popular World Literature Books«. https://www.goodreads.com/shelf/show/world-literature (last viewed on 27.09.2018).

- 25. Moretti: »Conjectures on World Literature«, p. 55.

- 26. Ibid., p. 57.

- 27. Venkat B. Mani: »Bibliomigrancy. Book Series and the Making of World Literature«. In: Theo D’haen (ed.): The Routledge Companion to World Literature. London a.o. 2012, p. 292. Mani’s argument refers to the language debate within postcolonial studies. There are, broadly speaking, two positions: those who advocate the use of former colonial languages such as English because these guarantee a wide dissemination (for example Salman Rushdie) and those who advocate writing in indigenous languages as an act of resistance. The fact that Ngũgĩ wa Thiong‹o who is known as a militant representative of the latter position published several books with the AWS, before rejecting English in favor of his native Gikuyu, points to the close entanglement of ideology and economy regarding ones positioning in the language debate.

- 28. The figures are based on the list printed in James Currey: Africa Writes Back. The African Writers Series & The Launch of African Literature. Oxford a.o. 2008, p. 301–310. The list comprises the 359 paperback titles of the AWS published between 1962–2003, of which 139 (38,7%) originate from writers/editors of West Africa and 304 (84,7%) from male writers/editors.

- 29. Ibid., p. 310.

- 30. Caroline Davis: »A Question of Power: Bessie Head and her Publishers«. In: Journal of Southern African Studies 44.3 (2018), p. 492, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2018.1445354. Davis refers to: Debora Richey: »Black African Women Writers: A Selective Guide«. In: Collection Building 14.1 (1995), pp. 23–31, and to: Ellen Banda-Aaku: »Playing Catch-Up«. In: Journal of Southern African Studies 40.3 (2014), pp. 607–613.

- 31. Davis: »A Question of Power«, p. 492. Davis refers to: Adeola James: »Ama Ata Aidoo (Interview)«. In: James (ed.): In Their Own Voices. African Women Writers Talk. London/Portsmouth 1991, p. 11–12.

- 32. I quote from the English translation/revision: Elke Sturm-Trigonakis: Comparative Cultural Studies and The New Weltliteratur. Translated from the German by Athanasia Margoni and Maria Kaiser. West Lafayette 2013, p. 5.

- 33. Ibid., p. 7. Rebecca Walkowitz’ description of Ishiguro’s novels as »examples of the new world literature« and of what she calls »comparison literature, an emerging genre of world fiction for which global comparison is a formal as well as a thematic preoccupation« bears some similarities to Sturm-Trigonakis’s conception. See: Walkowitz: »Unimaginable Largeness«, p. 218.

- 34. Sturm-Trigonakis: Comparative Cultural Studies and The New Weltliteratur, p. 7.

- 35. Sigrid Löffler: Die neue Weltliteratur und ihre großen Erzähler. München 2014, p. 18.

- 36. Ibid.

- 37. The German non-profit association Litprom (»the home of world literature in Germany«) hosted their fifth literary days under the motto New World Literature and The Global South. See: N.a.: »Neue Weltliteratur und der Globale Süden«. In: Börsenblatt (08.01.2016). https://www.boersenblatt.net/artikel-litprom_literaturtage_am_22._23._ja... (last viewed on 08.10.2018). In the same year, Sigrid Löffler launched the project Heidelberg Reads New World Literature. See: N.a.: »Neues Literaturprojekt im IZ: Heidelberg liest neue Weltliteratur«. In: IZ – Interkulturelles Zentrum (11.03.2016). https://iz-heidelberg.de/eroeffnung-von-heidelberg-liest-neue-weltliteratur/ (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

- 38. Mirosława Czarnecka: Frauenliteratur der 70er und 80er Jahre in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Wrocław 1988, p. 5, translation S. F.

- 39. Adele King: »The Longman Anthology of World Literature by Women, 1875–1975 (Book Review)«. In: World Literature Today 63.3 (1989), p. 543.

- 40. Ibid.

- 41. Jo-Ann Wallace: »Women’s Literary History in a Minor Key«. In: Katherine Binhammer and Jeanne Wood (eds.): Women and Literary History: »For There She Was«. Newark a.o. 2003, p. 204.

- 42. W.W. Norton & Company: »The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women«. http://books.wwnorton.com/books/webad.aspx?id=11623 (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

- 43. Formerly Orange Prize for Fiction 1996–2012 and Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction 2014–2017 (after its respective sponsors).

- 44. Women’s Prize for Fiction: »History«. https://www.womensprizeforfiction.co.uk/about/history (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

- 45. Gisèle Sapiro: »How Do Literary Works Cross Borders (or Not)? A Sociological Approach to World Literature«. In: Journal of World Literature 1.1 (2016), p. 92. https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00101009.

- 46. Michelle Johnson: »Editor’s Note«. In: World Literature Today 90.6 (2016), p. 5.

- 47. Anderson: »Of Gatekeepers and Bedtime Stories«, p. 13.

- 48. World Economic Forum: The Global Gender Gap Report 2018. Geneva 2018, p. vii. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf.

- 49. Ibid., p. 10 (overview) and p. 287–288 (U.S. in more detail).

- 50. According to UNESCO data from 2007, only 6.2 percent of all translations were made from languages other than English to English. See: Index Translationum: »Evolution in time for each target language«, http://www.unesco.org/xtrans/bsstatexp.aspx?crit1C=2&crit1L=4&nTyp=min (last viewed on 06.01.2019) and »Evolution in time for each original language«, http://www.unesco.org/xtrans/bsstatexp.aspx?crit1C=2&crit1L=3&nTyp=min (last viewed on 06.01.2019).

- 51. Anderson: »Of Gatekeepers and Bedtime Stories«, p. 13.

- 52. However, there are more and more such initiatives that carry out quantitative analyses of the literary market. Since 2012, staff of the Australian Stella Prize compiles the annual Stella Count, tracking the number of books by men and women reviewed in major Australian newspapers and literary magazines. See: The Stella Prize: »The Count«. https://thestellaprize.com.au/the-count/ (last viewed on 19.03.2019). In 2015, the Innsbrucker Zeitungsarchiv in Austria started their series Literary Criticism in Figures that provides information on quantitative developments in German-language literary criticism. See: Innsbrucker Zeitungsarchiv: »Literaturkritik in Zahlen«. https://www.uibk.ac.at/iza/literaturkritik-in-zahlen/ (last viewed on 19.03.2019). In 2018, the German research network Frauenzählen conducted a pilot study on the visibility of women in German-language media and literature. See: Frauenzählen: »Pilotstudie ›Sichtbarkeit von Frauen in Medien und im Literaturbetrieb‹«. http://www.frauenzählen.de/studientext.html (last viewed on 19.03.2019).

- 53. Amy King: »›Best of 2009‹ and ›Historical Count‹«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (29.03.2010). http://www.vidaweb.org/best-of-2009/ (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

- 54. Ibid.

- 55. The Nobel Prize: »Alfred Nobel’s Will [1895]«. https://www.nobelprize.org/alfred-nobel/alfred-nobels-will-2/ (last viewed on 08.10.2018).

- 56. Löffler: Die Neue Weltliteratur, p. 13.

- 57. The qualified nominators consist of (1) the members of the Swedish Academy and similar institutions, (2) professors of literature or linguistics, (3) previous Nobel Laureates in literature, and (4) presidents of leading national societies of authors.

- 58. In September 2018 Arnault received a two-year prison sentence over a rape committed in 2011.

- 59. Kelly Washbourne: »Translation, Littérisation, and the Nobel Prize for Literature«. In: TranscUlturAl 8.1 (2016), p. 57.

- 60. Maureen Freely quoted in: The Warwick Prize for Women in Translation: »About the Prize«. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/womenintranslation/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

- 61. Another noteworthy example of a literary prize that focuses on translated literature by women is the German LiBeraturpreis. Since 1988 it is awarded annually to a text written by a woman from Africa, Asia, Latin America, or the Arab World that was translated into German. See: Litprom: »Der Liberaturpreis«. https://www.litprom.de/beste-buecher/liberaturpreis/der-preis/ (last viewed on 07.01.2019).

- 62. Nicola Griffith: »Books about Women don’t Win Big Awards: Some Data«. In: Nicola Griffith (26.05.2015). https://nicolagriffith.com/2015/05/26/books-about-women-tend-not-to-win-... (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

- 63. »Goldfinching« after Weiner can be defined as »the collective actions taken by book critics to devalue those runaway literary bestsellers that are written and read, largely, by women«. See: Kristian Wilson: »Jennifer Weiner’s Coined Term ›Goldfinching‹ Is The New ›Mansplaining‹ For Readers«. In: Bustle (24.11.2015). https://www.bustle.com/articles/125946-jennifer-weiners-coined-term-goldfinching-is-the-new-mansplaining-for-readers (last viewed on 13.01.2019).

- 64. Jennifer Weiner: »If you enjoyed a good book and you’re a woman, the critics think you’re wrong«. In: The Guardian (24.11.2015). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/nov/24/good-books-women-readers-literary-critics-sexism?CMP=edit_2221 (last viewed on 13.01.2019).

- 65. N.a.: »About the VIDA Count«. In: VIDA. Women in Literary Arts (21.02.2012). http://www.vidaweb.org/the-count/ (last viewed on 09.10.2018).

- 66. Starting in 2010, VIDA has counted the gender of the authors reviewed as well as of their reviewers in the following 15 publications: The Atlantic, Boston Review, Granta, Harpers, London Review of Books, The Nation (no count in 2010), The New Republic, The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The New York Times Book Review, The Paris Review, Poetry, The Threepenny Review, Tin House (no count in 2011), and The Times Literary Supplement. In 2013 they began to include more than 20 further literary journals in their counts; those additional counts are referred to as the Larger Literary Landscape VIDA Counts.