Digitales Journal für Philologie

Eyes Be Closed: Franz Marc’s »Liegender Hund im Schnee«

The rejection of the general state of society, particularly its expression in art, and the elevation of the Tierbild to spiritual relic were fundamental concerns for Franz Marc. They are intimately connected to his intention to »intensify the aesthetic emotions … by blending the painted canvas with the souls of the spectator and the animal«, a desire which led him to declare that the human viewer must be »placed in the center of the picture«.1 The full understanding of this connection is central for illuminating the idea of Marc as a sort of naturalist who used the work of other painters as well as direct observation of animals and nature to challenge entrenched beliefs about spectatorship, pictorial space, and the consciousness of animals. Very much in the same way as historic and contemporary notions of Einfühlung imply a mode of spectatorship where both the body and the imagination have an important role, Marc’s aspiration to blend the painted canvas with the soul is grounded in an idea of perception where those souls are also embodied.

Thus while referential content became less and less recognizable in the work of Marc’s close associate, Wassily Kandinsky, for Marc creating entirely gegenstandslos painting was never a goal – though not my primary area of inquiry, this is an important revision in what we normally think of as the agenda of the Blaue Reiter. In proposing a combined interpretation of paintings, artists’ writings, and the contemporary art environs Marc worked in, I aim at understanding the process of looking at Marc’s art as a social practice construed though the interaction of artist, animals, and viewers in specific environments connecting images, words and, in Marc’s estimation, a sort of spiritual intuition. I devote particular attention to Marc’s vocabulary and choice of titles and modes of representation for his portraits of his dog, Russi.

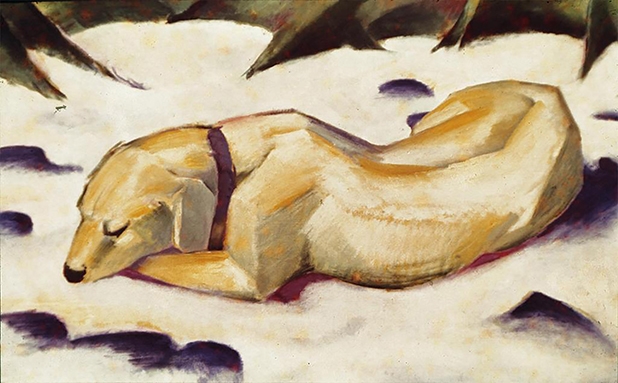

Examined here are a representative sample of the type of painting that makes a case for this interpretation, Marc’s Liegender Hund im Schnee (Figure 1), to offer a detailed description of how this process of observation, appropriation, execution, and interpretation works. This extended analysis provides the necessary background to assess more fully the nature of the leap in the thought behind making and viewing paintings of animals which Marc thought was necessary both to appreciate the new art and connect the idea of a lost paradise with a utopian future.

»The Hound and the Horse«

In thinned oil pigment on a large horizontal canvas, Franz Marc painted a portrait of a white dog, his own Siberian sheepdog Russi, in comfortable repose on a blanket of

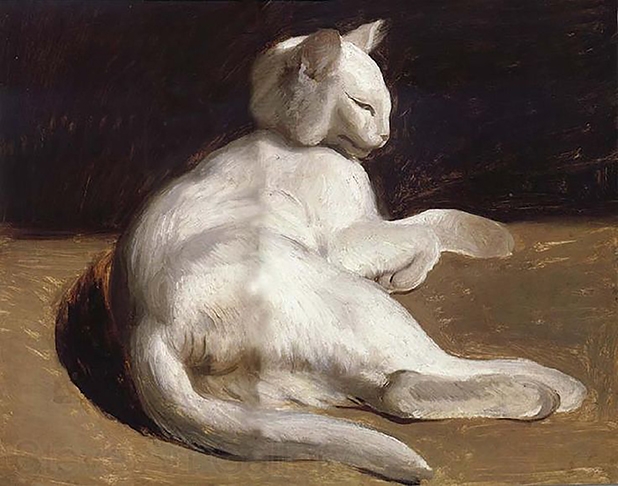

Figure 1. Franz Marc, Liegender Hund im Schnee (1912). Städel Museum, Frankfurt. Oil on canvas, 62.5 by 105 cm.

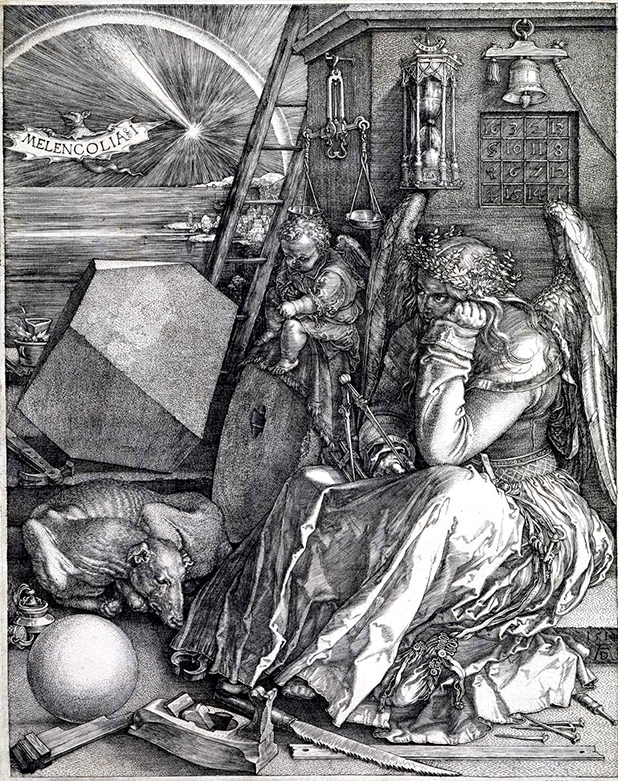

snow that under the warmth of the dog’s body has begun to melt. Russi closes his eyes in the satisfied contentment into which he has retreated. His body represents the unity inherent in the almost oval shape he occupies within the picture, echoing the mix of angles and contours from the wedge of his head to the rounded haunches under which his rear legs are folded. The stillness of the dog’s body and the undisturbed, slowly melting snow indicate that the dog is in a state of calmness and relaxation. Russi extends his left foreleg so that his chin rests upon and is supported by his paw, a position that, through iconographic tradition in German art, telegraphs a pensiveness that will resolve into renewed creative energy (Figure 2).2 The position of Russi’s body and the nest-like arrangement of the tree trunks and patches of earth in the surrounding space leave little doubt that the dog intends to linger in this state for some time. The large size of the canvas (65 by 105 centimetres), and the dominance of Russi’s occupation of it, place the dog in the viewer’s phenomenological space – at human eye-level – and enfolds beholders into a sense of being protected and undisturbed. Marc’s radical, sophisticated simplification of the palette and attentive treatment of Russi’s individual characteristics – the dog wears a violet martingale marking him as a member of the Marc household – give a direct and appealing clarity to the image.3

The painting was one of the first accessioned to a major museum collection following the artist’s death in 1916, purchased directly from his widow, Maria Marc, and was first displayed by the Städtische Galerie im Städel, Frankfurt, in 1919.4 The Städel was forced to part with the painting in 1937 when it was seized as Entartete Kunst and housed briefly

Figure 2. Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I (1514). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Engraving, 24 by 18.5 cm.

at the Depot Schloß Niederschönhausen near Berlin. Fortunately, perhaps, as Felix Weise, an early collector of the avant-gardes and the primary patron of Emil Nolde, remarked in a 1914 letter to the Bürgermeister of Halle, Richard Robert Rive, the painting of a family pet was a prize of little value »even for something dangerously pleasing«.5 The painting however escaped destruction, and after a convoluted journey returned to the Städel for good in 1961.6 The historical evaluation of Liegender Hund as lovely but uncomplicated may have helped it avoid iconoclasm, but its lack of the fraught sense of other Expressionist works has perhaps kept it away from the critical historiography and analysis it deserves.

It is true that at first glance its subject seems not to place the painting amid the lofty ambitions of the leading artists of the Modernist counterculture in Germany in their battle against the dominance of conservative, academic art. What then was Marc’s intention with this portrait of his beloved Russi at the time of its creation? Liegender Hund im Schnee was made in the months during the production of the Blaue Reiter Almanach, before its publication in the summer of 1912. Marc and his collaborator Wassily Kandinsky had designed and edited the unorthodox yearbook which debuted in May, distributed by Reinhard Piper.7 Kandinsky’s important theoretical treatise Über das Geistige in der Kunst also appeared in 1912, as well as the epoch-making modern art exhibitions of the European avant-garde by both the Blaue Reiter in Munich and the Sonderbund in Cologne.

The Blaue Reiter artists and their circle were exceedingly active in 1912, with the exhibition at Tannhäuser’s Galerie der Moderne in Munich in January 1912 quickly followed by a spring show at the Hans Goltz bookstore/art shop in Munich and a pop-up appearance at a temporary space on the Tiergartenstraße in Berlin organized by Der Sturm impresario Herwarth Walden, which then went on to tour around Germany. The antagonistic catalyst for the Blaue Reiter’s flurry of activity was a well-publicized fracas in the German art world: In the winter of 1911, as Marc was making Liegender Hund im Schnee, the Worpswede painter Carl Vinnen distributed a pamphlet condemning foreign artists, including Kandinsky; the preference of German museum curators, specifically Marc’s good friend, Hugo von Tschudi of Munich’s Neue Pinakothek, for purchasing and collecting the work of French painters including Paul Gauguin, Édouard Manet and Henri Matisse; and generally castigating the early avant-gardes.8 Particularly in Bayern, where what it meant to be German versus bayerisch was a continual cultural issue, populist, imperial, and local party politics played a role in such artistic confrontations; however, the key issue was financial, as from 1900 the purchase of local artists’ work as a sort of consolation stipend was ruled out by a lack of public funding.9 By the summer of 1911, Piper, who with Walden had established themselves as the go-to publishers for Modernist journals, had collected the heated responses of prominent curators, gallerists, artists and writers, including Kandinsky and Marc, which, under Marc’s urging, Piper titled Im Kampf um die Kunst. Antwort auf den ›Protest deutscher Künstler‹ mit Beitr. deutscher Künstler, Galerieleiter, Sammler und Schriftsteller.10 Emphasizing the importance of a common goal and casting the struggle as one of the interests of group welfare over and above individual wellbeing was articulated clearly in Marc’s essay.11

In short order Marc and Kandinsky found even the generally progressive NKVM (Neue Künstlervereinigung München), of which they were members at the time of the ›Vinnen incident‹, too timid and rigid for their purposes.12 Thus by 1912 the breakaway Blaue Reiter stood not just as an artistic confederation but also as the creators of a sort of alternative journalism as well as the proponents of an international style of art that was politically left-leaning and utopian.13

And the dog resting in the snow? What is the role he plays in all of these machinations? With the christening of the Blaue Reiter, another animal – the horse – had become the emblem of the group, the companion of the rider who heralded the ‹fight for art› and who took up the arms of the avant-garde’s rhetoric. This motif is based upon the ›rider‹ as St. George, its background in Medieval Christianity.

This new art of course was perceived by the public and by most art critics as a radical departure from all the hitherto valid norms of art, and – when not denounced as mere incompetence – was deplored as aberration in its departure from Western culture.14Along with Vinnen, in January 1911, in his contribution to Ein Protest deutscher Künstler, Hans Rosenhagen accused the members of the NKVM (of which Marc at this time had just been invited to become a member) including Kandinsky, Münter, Alexander Jawlensky and Marion Werefkin, of »not only harming themselves by foolishly aping every French madness but also contributing to lowering the reputation of German art«.15

Rosenhagen declared of Matisse, one of many French painters whom Marc admired (and whom von Tschudi had collected), that he gave preference »to the products of South Sea Islands and Dahomey art over the wondrous creations of Greco-Roman culture«.16

To critics like Rosenhagen this association of modern West European art with the art of the natives of New Caledonia and of a West African kingdom was evidence of madness and derangement, while for the Blaue Reiter artists themselves and their partisans it was viewed positively. The derogatory term ›Fauves‹ applied by the conservative critic Louis Vauxcelles in 1905 to the artists around Matisse had instantly been adopted by them as an honorific title. Rosenhagen copied Vauxcelles’ stigmatization of modern art by entitling his contribution Die ›Wilden‹, which Marc proceeded to turn around, using it in the title of one of his three Blaue Reiter Almanach articles: »Die ›Wilden‹ Deutschlands«.17

Among German avant-garde artists deserving this flattering designation Marc included those of the Brücke group in Dresden, the Neue Secession in Berlin, and, at the time of his writing, the Neue Künstlervereinigung München. On the other hand, only where there was »a rebirth of thought«, and not just a formal renewal of art, could one speak of »savages«.18 For Marc what was at stake was a new status for art that was at once to be forward-looking and new and at the same time to be as binding to spirituality and ritual as totems in pre-modern societies. Marc’s utopian vision dreamt of being on the threshold of an epochal change, comparable to that from antiquity to the Byzantine – though what Marc sought was to change things back to a pantheistic paganism.19

The art of the ›savages‹ would proclaim this new era, a spiritual age, for which it would produce new symbols. The ›savages‹ are thus the artist-heralds of this »vita nuova«.20 This construct however also created a problem that abraded Marc’s avowed socialist and communal beliefs: Until art recovered its iconic status, and pictures again became symbolic religious tablets, the artist could not vanish behind his creations in the anonymity of the cult, but, on the contrary, must expose himself through his radical identity – as a savage, as a primitive, as a martyr.21

»Recueillement and Recovery«

Despite his public bravado in the Vinnen matter, while fighting on the front lines of this battle for the new art, Marc was in the throes of a severe depression.22 He retreated to the countryside to regain his concentration and to reclaim his unrest from what he deemed the superficial materialism of the city.23 In fact by the end of 1910 Marc had already given up his apartment in Munich entirely in favor of the Oberbayern village of Sindelsdorf. There, Helmuth Macke, the teenage cousin of August Macke, came to stay with Russi, Marc, and Marc’s assortment of cats, cows, horses, and orphaned fawns.

In 1909, Gabriele Münter had bought a home in nearby Murnau where she lived with Kandinsky until 1914. Between Murnau and Sindelsdorf, Kandinsky and Marc, grew from spring 1911 a friendship, a sense of collaboration, and a series of visits along with other companions or guests. They took often long walks together followed by evenings spent discussing how to concretize the idea for a publication that would express both their ideas. In this restrained urban exodus, with its traces of therapeutic reform, plans for this joint venture thrived.

Seen in the context of this sanity-regaining retreat, the recumbent white dog is the necessary genre-counterpoint to the symbolic horse of the Blaue Reiter, and another facet of Marc’s personal identification with animals and his association of nature in general with recueillement.24 While the horse represented the outward struggle for the new art, championing values from the world beyond made manifest in the real world, the portrait of Russi was drawn from the depths of Marc’s quiet contemplation of a corporeal animal that he loved. In the quiet countryside, in the relative support of human and animal friends, Marc was able to sink himself into the stillness of the contemplative dog, which exudes dreamy innocence and tranquillity.

»Not Sleeping, Dreaming«

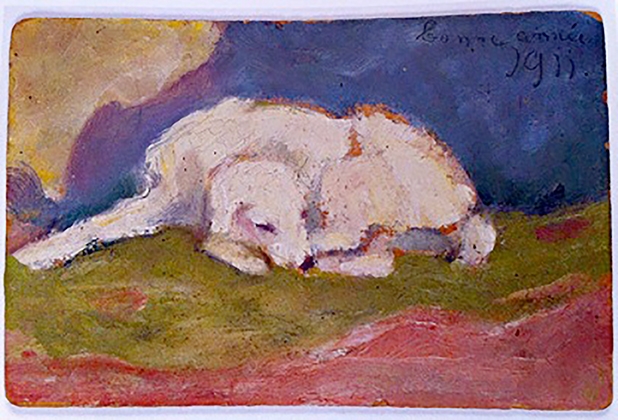

How did Marc come to the choices he made for Liegender Hund im Schnee, from its name to its conceptual and formal components? Klaus Lankheit’s extensive writings on Marc, and also his then-comprehensive catalogue of Marc’s paintings, lists the title simply as Der Weiße Hund as does Alois Schardt’s 1936 Franz Marc, the first effort at assembling a catalogue raisonné of the artist’s works.25 In the more recent Marc catalogues raisonné by Annegret Hoberg and Isabelle Jansen the title is appended to add Liegender Hund im Schnee in brackets, which is how the painting is known, without the brackets, at the Städel.26 I believe that this title is still not authentic, as Marc’s letters to Maria Marc and Macke make clear he intended the work as a portrait of Russi in particular. Marc had made another, small (9.5 by 14.4 cm) oil on cardboard painting of Russi in a similar pose, apparently intending to send it to August Macke as he had scratched »Bonne année 1911« in the upper right hand corner of the painting, and carefully inscribed »Liegender Russi« on the reverse (Figure 3), which is the name he gave to other iterations of Russi in his sketchbooks.27

Figure 3. Franz Marc, Liegender Russi (1910). Private Collection. Oil on cardboard, 9.5 by 14.5 cm.

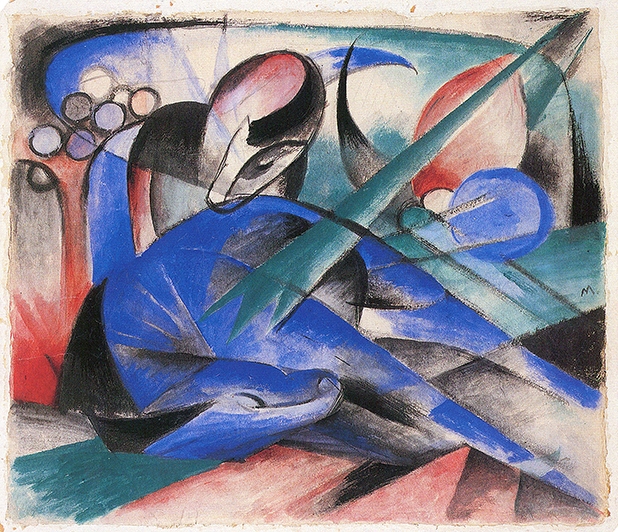

This evidence suggests Marc had intended to use Russi’s name in the title. My interest in the minutiae of nomenclature is relevant as my other primary concern here is Marc’s choice of the word Liegender, which seems a careful differentiation from many of his other paintings (such as, for example, 1913’s Träumendes Pferd) (Figure 4) of animals and people as well as those who are described as sleeping or dreaming.28

But Marc was not interested in depicting psychic lethargy. The unfinished, simplified aspects of Liegender Hund im Schnee momentarily confuses and destabilizes the rapid processing of information and creates vulnerability, and our eyes require other senses to be brought in to help interpret the image. In the way that someone learning a language touches a printed page to make out a word, the strong outline of the dog makes us want to trace his outline with our fingertips, to touch Russi the way we would a real dog. Marc makes use of Russi’s shape and contours – which are rendered with definite dark strokes, leaving the details of the dog’s fur tantalizingly obscure. Visually this brings together the precise and the speculative, suggesting that while there is much we can know about Russi, we cannot know everything – affirming that there is after all something to know. Russi’s subjective reality is shown in a way that makes his state evident to viewers, and in this portrait of his companion and frequent artistic subject Marc is especially astute in conveying the intense privacy of the dog.

Figure 4. Franz Marc, Träumendes Pferd (1913). The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City. Watercolor, 40.4 by 46.3 cm.

As Marc reinforces in his discussion of the prism, spectral colors are not used for the sake of being complementary.29 Both Russi and the snow retain local color, and the dog’s body in the foreground of the painting conveys a dominating mass. But it is Russi’s somnambulance that is the subject of the painting, the inaccessibility and privacy of his psychological world. The dog’s still body, a pale, reflective, and yet flat and stolid surface, houses a contemplative ensouled subject who transforms the natural objects in the landscape into the subjects of his own imagination. So here in fact Marc accomplishes »the pantheistic immersion into […] trees, animals, air« he had described in the unedited version of his letter to Piper about Animalisierung.30

The eradication of the extraneous draws attention not to Marc’s virtue as a renderer but rather to Russi’s sentiency. Showing Russi in the ether between conscious and unconscious states underscores our awareness of the dog’s mindedness; certainly the demiworld of daydreaming or meditation is one of the most rarefied aspects of livingness.

In German academic and cultural dialogues in the first decades of the 1900s, psychology and aesthetics were aligned more closely than they are now – Wilhelm Worringer’s watershed Abstraktion und Einfühlung (1911), embraced by artists including Kandinsky and Macke, was as much a rebuttal to Theodor Lipps’ two-volume Ästhetik (1903–06) as it was an art historical treatise. Marc expressed disdain for the therapeutic aspects of psychoanalysis, but he was certainly aware of its currency in the circles in which he worked.31 Sigmund Freud’s classic case of Félida X. is in fact a study of somnambulism and dreaming. Heretofore the distinctive characteristic of somnambulism had been forgetfulness on waking of what had taken place. Dreaming manifested other forms of forgetting, in which the self was no longer able to recognize certain memories as its own, and formed characters which were »doubles« of the dreamer. Experiments with hypnotism underscored the strength of such an individual’s »subconscious fixed ideas«, which Freud traced back to the subject’s childhood. Hypnosis as a therapy had shown that unconscious ideas can be dynamic, but Freud’s replacement of the idea of forgetfulness with that of repression marks the transition from the 19th to the 20th Century psychological precepts.32

Acknowledging the unknowable state of the dog’s mind, Marc made much of Russi’s considerable physical presence, often using Russi as a model, both as a subject for several other major paintings such as Sibirische Schäferhunde (Sibirische Hunde im Schnee) from 1909 (Figure 5) and he also practiced drawing the dog in many iterations in his sketchbooks. See for example the sketch, Liegender Hund (Russi) (Figure 6), (note both the title and Russi’s name inscribed on the left-hand side) which shows that even before he began to wrangle with the problem of color, Marc was busy practicing making copies and models for his later paintings, sketches which nonetheless stood as discrete works for Marc, since, in his somewhat haphazard fashion, he also named and numbered them. Certainly in addition to seeing Russi as a real, historical dog, he may also be viewed as representative of his specific breed of dog, an Ovcharka, or type of herding dog originally from Russia. Thus Russi – perhaps in contradiction to Marc’s intentions – can also vouch for an entire genus, »[…] vom Menschen taxonomisch zugerichtetes Tier, das eine biologische Artbezeichnung als Kennzeichnung vor sich herträgt.«33

Figure 5. Franz Marc, (Sibirische Schäferhunde) Sibirische Hunde im Schnee (1909). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Oil on canvas, 60.5 by 60 cm.

Figure 6. Franz Marc, Liegender Hund (Russi) (1909). Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg. Pencil on paper, Sketchbook XI page 2, inscribed Russi V 09, 12.4 by 19.2 cm.

Because of this association with the canine in its multitude, it is understandable that this painting has been taken as a rather typical representation of a dog, doing something that dogs often do, arranging themselves in a comfortable reclining posture, their humans not far away. The few art historians who have discussed this painting besides myself have also tended to assume that Russi is sleeping.34

Instead we should see Russi as in a contemplative state between sleep and wakefulness and that moreover there is much in Marc’s research as a naturalist (in terms of observing both art and animals with an eye toward making accurate field studies) that supports this reading. It is true that because of the simplification Marc discusses as part of his experimental process in the letter to Macke, it is impossible to determine with certainty if Russi’s eyes are fully closed or partly open. But Marc knew that dogs, waiting for their people, are likely to doze without fully committing to sleep; especially in helping his human with a task, one he was accustomed to, the dog would not choose to become fully unconscious and oblivious to his surroundings.

Beyond intuition and deduction, and keeping in mind Marc’s practice of observation, replication, and adaptation, Marc gives clear signs of the appropriation and modification of both the words and images of other painters, in the interest of homage as well as plotting a position on the timeline of the emerging new painting. Through Liegender Hund im Schnee, we can observe the evolution of Marc’s practice as a painter and naturalist. Compare this image of Russi with an animal portrait by one of the French painters Marc admired, created nearly a hundred years earlier: Théodore Géricault’s Le chat blanc from 1814 (Figure 7). Marc had encountered this painting in the Louvre on his first trip to Paris in 1904, an occasion he makes note of in his journal.35 Upon returning from Paris in 1905, Marc immediately experiments with Géricault’s use of contrast and cropping in Der tote Spatz (Figure 8). Marc’s treatment of the attributes of the sparrow – body shape, proportions, placement within the space of the picture – indicate close and thoughtful study both of the bird and Le chat blanc. The gestural brushwork of the sparrow’s feathers, made from patches of side-by-side color, connects French representational painting with elements of Abstraktion and simplification. The pictorial surface is defined by its intimate nature; the limited tonal background restrains the maudlin while reinforcing the feeling of being very close to the tiny subject.

Figure 7. Théodore Géricault, Le chat blanc (1817). Musée du Louvre, Paris. Oil on canvas, 55 by 66 cm.

Figure 8. Franz Marc, Der Tote Spatz (1905). Private collection. Oil on wood panel, 13 by 16.5 cm.

Six years later, having become a formidable innovator of animal painting in his own right, Marc looks again to Le chat blanc for inspiration in how to solve some of the formal painterly problems he raises in his correspondence with Macke with regard to tonalities of white, and, perhaps even more significantly, for how best to make the mise en scène serve the being of the dog. The use of space and the relationship of the viewer to the size and placement of the dog within the canvas show Marc’s intent to both invoke and subert the older tradition.

Like Géricault, Marc uses defining features of the animal, such as the mouth, eyes, feet and ears, to highlight their specific characteristics.36

Crucially, with Géricault’s placement of the cat’s limbs and raised head and neck, the undulation of its lithe body underneath its irregularly shaded coat, and even the detailed treatment of the position of the cat’s ears, Géricault does give us the sense of a sentient and alert being, even though the animal could also be taken to be resting or napping. Marc brings a more holistic sense to his composition through treatment of the dog’s immediate environment as something more than a formal incidental, and creates a dog more in symmetry with his habitation of an elongated, egglike, rather than square, shape.

Géricault arranges his canvas so the presence of the cat confronts us, its body protruding not only over the cushion it nearly covers, but also the cat’s tail abuts the edge of the lower frame, making its robust presence clear, but also commenting on the artist’s relationship to the cat – that the painter is able to both get close to the animal and have it be calm long enough thus for the purpose of being painted. Marc renounces both this assertion of artistic ego and the dramatic, almost demonizing, characterization of the bodiliness of the cat, of its mortality, by concentrating on the balanced sense of composition form, on symmetry, and on a very limited color palette to create an impression of clarity and coherence, leaving a sense of uncertainty radiating from the dog’s interiority.

Marc strives to capture a spontaneous perception that is at the same time not random, to allow for a visual impression that will be enhanced by close observation. He does this by framing Russi as the central subject of the painting to the point where Russi almost fills the frame, a variation on the tactic used by Géricault. Although Russi is lying upon the ground in the painting, Marc’s literal elevation of the canine subject places him at the viewer’s eye level, contributing to Russi’s monumentalization. The pictorial space is no longer coherently organized according to the rules of central perspective – both Le chat blanc and Marc’s Der tote Spatz dramatize the placement of the animal with a neat, horizontally split, contrasting background. In Liegender Hund, because this space is no longer organized according to the rules of human rationality, the genre animal painting is disrupted, and the implication is that Russi is somewhere beyond the dimension of our own existence is emphasized.

This arrangement also serves a generally unifying objective from both formal and interpretive perspectives. While the trunks of the trees call to mind zoomorphic echoes of the blunted angles of Russi’s back and his connection to the earth, the heightened polar and blue tones of the snow make a sort of negative-contrast to the fur of the dog, who is also white.

The violet tones underneath Russi’s body and the lilac of his collar also serve a dual purpose, giving a tactile sense of decorative familiarity in the latter, and a sense of the warmth of the dog’s body, which melts the snow, in the former. The use of these blended colors of course further refutes scholarship taken as gospel what are in fact Marc’s playfully imperious statements to Macke about ›color principles‹.37

The tonal white-on-white design, which achieves its plasticity by means of contouring blue-tinged and yellow-tinted shades with greys and the strong charcoal outline of Russi’s body, is complemented by shadowy zones around the tree trunks; hence the dog’s corporeality is also experienced empirically as a reflective, though dense object. This provides a structural counterpoint of gravitas, so the image is anchored with more than its elegant linearity.

Through these deceptively simple tactics and schemes, rising to a type of semiotic game, Marc makes clear that ›dog‹ is not a minor species of animal subordinate to ›human‹ but rather that Russi should be elevated to the pantheistic firmament of spiritual veneration, the claim he makes about his intention for animal paintings, but in this case equally personal and general.38

However, in this sense, Marc’s project in making this painting was nonetheless a continuation of the NKVM’s attempt to create a new appreciation of the decorative and ornamental as applied to painting and to investigate a synthesis of color and surface as a new pictorial language of the sublime.39

The embedding of an animal in an abstracted environment is done not only to emphasize the dog as central subject. Though it makes sense that what we are looking at are the trunks of the trees encircling Russi, the cropping of the scene and the truncated view of only the tree roots creates a somewhat uncanny effect; the roots take on a somewhat cosmic aspect, like a celestial dome. Like the dog, the tree trunks make a rounded, oval arch, the overall shape differentiated by contouring and contrast.

Such »eine Animalisierung des Kunstempfindens,«40 should thus be not only a sensation of the human viewer’s eye, but a synaesthetic perception of the animal’s sentience including aural impressions, sensations of cool and warmth. Veit Loers references this so-called »Sinnesversetzung« in this context as a parallel to such occult phenomenon often associated with Kandinsky’s interest in this subject, such as the ability to see with the fingertips or hear with the solar plexus, and describes it in the vocabulary of Mesemerism as »magnetischen Schlafes«.41

In fact Marc himself characterized his mode of trying to perceive as the animal as if in a state of somnambulism, partly conscious yet also given over to the transformative experience of being another, in this dream-like state. The animals to Marc possessed in their purity a sort of natural somnambulism. His work has numerous examples of such a ›sleep-waking‹ state, corresponding to the posture of animals, and also people, in a relaxed posture reclining into a receptive earth. This natural somnambulism blurred what was conventionally taken to be a distinction between people and animals, that animals are innate and instinctive, whereas humans can return to this state only in dreams. In 1911, Marc had written an interesting personal aside in his journal:

›[Können wir uns ein Bild machen, wie wohl Tiere uns und die Natur sehen?]

Gibt es für Künstler eine geheimnisvollere Idee als die [Vorstellung], wie sich wohl die Natur in dem Auge eines Tieres spiegelt? Wie sieht ein Pferd die Welt oder ein Adler, ein Reh oder ein Hund? Wie armselig, [ja] seelenlos ist unsre [Gewohnheit] Konvention, Tiere in eine Landschaft zu setzen, die unsren Augen zugehört statt uns in die Seele des Tieres zu versenken, [daß wir das seinen Blick Weltbild] um dessen Bilderkreis zu erraten.

[Diese Betrachtung soll keine müßige causerie sein, sondern uns zu den Quellen der Kunst führen.]‹42

We can see this interest in the perception of animals reflected not just in Marc’s belief in the inherent Beseeltheit43 of animals but also in his knowledge of contemporary zoology research taking place at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries, for example, the writings of Wilhelm Bölsche on plant and animal taxonomy44 and more clinical examinations, such as studies about how the retinae of insects’ eyes functioned.45

Thus what we think of now as »the question of the animal« was under Marc’s consideration in suprisingly contemporary terms, and should not be considered merely an outflow of his private, sentimental feelings about his pets. Like Kandinsky, Marc was curious as to whether there was a tangible basis for their claims that there existed unseen dimension in the regular order of the world but which had become invisible to callous, spiritually deprived humans.

»The Search for Paradise«

But for Marc the animal was also directly connected to the idea associated with the paradisiacal state of origin for which humans secretly yearn. These notions of a healing regression as a new religion, an inner sense of the state of things that could also in some manner be visualized and intellected, had been already been glancingly addressed by another artist by whom Marc was greatly impressed with and influenced by, Paul Gauguin. During a second trip to Paris in the spring of 1907 Marc writes a letter to his future wife Maria Franck in which he exclaims: »Ich sah mir nur wenig anderes an als die beiden großen neuen Meister van Gogh und Gauguin!!«46

Though his life and work are considered in a vastly different context now, in the first decades of the 20th Century, Gauguin quickly came to be treasured by the Brücke and the Blaue Reiter, particularly by Marc, who interpreted the artist’s adventures in the South Pacific as a valorizing search for the origins of religion as a means of cultural renewal. These sentiments are reflected in Gauguin’s travel journal Noa Noa, which Gauguin began during his first stay in Tahiti from September 1893 to March 1894 as an account of his arrival on the island and gradual immersion into its ›foreign‹ customs.47

An abridged version of Noa Noa was published in 1901 as well as excerpts from the book, which appeared in German translation in 1907 as a supplementary issue of Kunst und Künstler, the magazine published monthly by Bruno Cassirer of which Marc was an avid follower.48

In Noa Noa, Gauguin presents himself as the narrator of a journey back to the roots of indigenous culture, and at the same time, as a navigation inside of himself. It must have seemed to Marc the ›feeling in‹ to the estranged, ›original‹ nature and culture of the Maohi also leads to Gauguin’s conversion into a sort of ›savage‹. The topos of originality is the theme of the paintings Gauguin produced during his two visits to Tahiti. These unspoiled vistas, such as Arearea (Joyeusetés) (1893) (Figure 9), which often feature domesticated but unfettered animals wandering about freely, were a great influence upon Marc. Gauguin’s mingling of originary innocence and ›wildness‹ provided an element of strangeness, of something new, in European painting, but also nourished Marc’s longing to suss out the essence of existence in terms of how painting could convey the concept of Weltdurchschauung over and against Weltanschauung.49 The characterisation of alienation and acclimation as a religious experience was evoked for Marc in Gauguin’s image world: the primitive present as an earthly paradise.

Figure 9. Paul Gauguin, Arearea (Joyeusetés) (1892). Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Oil on canvas, 75 by 94 cm.

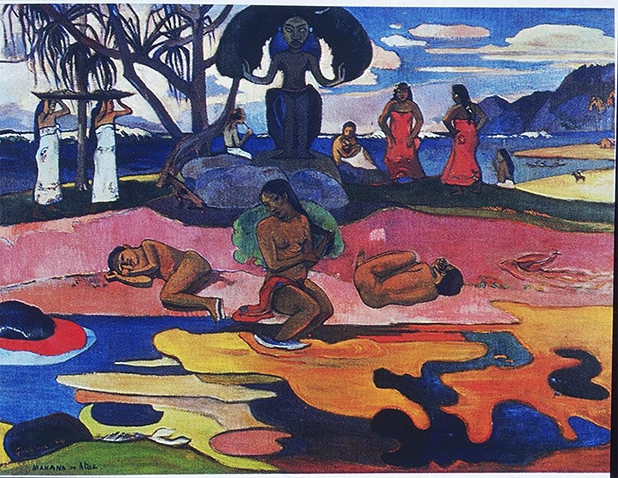

For example in the painting Mahana No Atua (Le jour de Dieu) (1894) (Figure 10), behind the figures reclining on the beach in the foreground there is a scene of a ritual. Women bring totemic figure offerings of fruit baskets, swaying as part of the rite of sacrifice. These solemn figures give an air of religious significance to the event.

Figure 10. Paul Gauguin, Mahana No Atua (Le jour de Dieu) (1894). The Art Institute, Chicago. Oil on canvas, 98.3 by 91.5 cm.

Traces of Gauguin’s themes become tangible thenceforward in Marc’s paintings: in the treatment and placement of the characters, but above all in the expressive power of firmly delineated and brightly coloured surfaces, which were commonplace as stylistic choices in Gauguin’s work but which Marc deepened and broadened to further expand into a metaphysical dimension, comparing, as examples, Gauguin’s L’esprit des morts veille (Manao Tupapau) (1892) and Marc’s Liegender Akt in Blumen (1910) (Figures 11 and 12). Though Marc was enthusiastic about Gauguin’s experiences and techniques, he also wanted to put some distance between himself and Gauguin’s morality and aesthetics.50

Figure 11. Paul Gauguin, L’esprit des morts veille Manaò tupapaú (1892). The Conger Good- year Collection, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. Oil on cloth, 116.05 by 134.62 cm.

Figure 12. Franz Marc, Liegender Akt in Blumen (1910). Private Collection. Oil on canvas, 72 by 100.5 cm.

Proceeding from here, we can look again at Marc’s adoption of this motif in terms of observation, appropriation, and naturalistic modification. Following Gauguin, Marc began making recognizable variations of the French artist’s work as precursors to the images of daydreaming animals whose inner visions he attempts to capture.

Unlike Gauguin, to Marc, nude women in a natural setting were not excuses for a prurient gaze but rather these women, like Marc’s contemplative animals, symbolized innocence and purity, and were associated with the reclamation of paradise. Dreaming animals and people stood for a somnambulant state marking a kind of emotional perception that synaesthetically included auratic impressions and warmth.51 In his painting Der Traum (Figure 13) in which a so called ›Wilden-woman‹ sits cross-legged, Marc blends this image of longing for an original paradise with the European idea of paradise, where the wild lion lives in peaceful harmony with horses and humans. Marc’s Animalisierung is in evidence here. Like ›wild‹ people, animals as envisaged by Marc display a natural somnambulism, having been born directly into their instincts, which modern humans – expelled from paradise – have lost.

Figure 13. Franz Marc, Der Traum (1912). Thyssen-Bornesmisza Museum, Madrid. Oil on canvas, 100.5 by 135.5 cm.

Meanwhile Marc worked diligently to ensure that the sacred meaning of the animals was brought forward, to show that their life forces exerted a power over the scenery, and that they were not just part of a painterly diorama.52

Gauguin was becoming more well-known during this time by other German artists, being the subject of the Deutsche Kunstgewerbeschau in Dresden in 1908 and finally arriving for a solo exhibition in Munich in 1910. Additionally, artists circulated photographs of what were beginning to be recognized as, ›electrifying‹ new French masterpieces, as reported by Marc’s correspondent from the Brücke, Fritz Bleyl.53 So Marc was aware, and in fact made certain, that his formal nods to Gauguin would be easily recognized as references to the originary, wild, and innocent.54

The theme of the tenuous life of the psyche between sleep and wakefulness is central to the living beings in the work of both Gauguin and Marc. This state of partial consciousness is of crucial importance for the recovery of innocence and the introduction of a new sense of spirituality, as Kerstin Thomas has discussed.55

Looking again at Le jour de Dieu, two of the figures lie in a curve at the edge of the water, similar to the placement of Russi’s body in Liegender Hund. The women are not sleeping, involved rather somehow in the ceremony going on behind them. Like Russi, their condition is ambiguous, characterized by relaxation, a lapse into a state of retreat and at the same time increased attention.

In a letter to the critic André Fontainas Marc would have known from his reading, Gauguin reflects on his impressions of the Tahitian dreamscape. He writes:

›Here, in the vicinity of my house, I dream in complete silence of mighty harmonies […] animal figures of statuesque rigor; something old, sublime, religious in their yesterdays, a rare kind of immobility. Their dreaming eyes move across the surface of an immense mystery. And then it will be night; everything rests. My eyes close to dream in the infinite space that flees before me, without understanding […]‹56

Gauguin binds together here the astonishment he feels about being amid the Maohi, as well as his longing for an original experience in imagining such a scene, in which the characters inhabit an ambivalent status between animals and gods, naively sublime and at the same time consciously religious.

Of course Gauguin’s approximation of and approach to the culture of Tahiti is characterized by chauvanistic stereotypes. However, by anachronistically appraising Gauguin’s texts and paintings in the hopeful and naïve context in which Marc would have received them, it is possible to see how Marc would have been galvanized by Gauguin’s practice as one which successfully introduced the combined ideas of longing for paradise with a contemporary spiritual dimension. Gauguin further provides a hint for Marc that the key to entering this new paradise is through adopting a sensibility that removes the rigid separation between reality and dream, between thinking and feeling.

Marc, therefore, unlike Gauguin, soon moved on. True to his culture-critical escapism, he finally replaced even the human ›savages‹ with animals, which were to become the most important subject of his pictures. Just as, in the course of his essentialist reduction, European nudes had ceased to seem innocent enough to him, so too the ›savages‹ – corrupted by Gauguin, Emil Nolde, and others – became insufficiently elemental in his eyes, until finally animals alone were allowed that more perfect, earlier-life status. In them was enshrined the memory of that paradisal, original state that humans yearn to regain. Seeing the world through the eyes of animals, for Marc, means to exact a new understanding of the world from human beings. Marc chose alienation in order to return something essential to his own alienated condition. Thus, seeing through animals’ eyes, with Einfühlung, is to invite a new world outlook for human beings, an essential view of things in their precultural, undivided wholeness. This process will enable human beings to understand nature on its own terms again; and in Marc’s terms: not just to see nature but to see through it, a penetration of matter via a medium.57 The half-closed eyes of Russi, the awake sleeper, show that the fully-minded activities extend to animals, but at the same time that an increased epistemic potential comes from a sort of self-imposed psychological hibernation.

Weltdurchschauung over Weltanschauung

Besides the intrinsic value it had for him personally, Marc urged viewers to look at the world through the eyes of animals as a way of more generally practicing Weltdurchschauung over and against Weltanschauung. As a process, considering the world from an animal’s perspective, Weltdurchschauung demands a sort of doubled aliention factor, both from one’s own culture and in acknowledging the distance we have traveled away from understanding the animals and how difficult it will be to return to what Marc describes as a tierhaft and instinkthaft state toward Animalisierung itself.58

In Liegender Hund Russi represents the instinctive originality of animal sentiency and its loss of comprehension to us. He is transformed into both himself – an animal subject inhabiting and creating his environment (a novel act in painting) – and an idealistic pictorial allegory. Russi is also an emblem for the art of the future, the »wirklichen Kunstformen,« of which Marc writes in a March 1915 letter to Maria Marc that this »[…] wahrscheinlich nichts als dieses somnambule Sehen des Typischen, das Sehen zwingender (und daher richtiger) Spannungsverhältnisse«59.

What can be considered an enhanced position on the elusive somnambulism in 1912 becomes fully realized in the form of Marc’s affirmative metaphysics toward the coming war, which he characterizes in some haunting predictives. In 1913 Marc painted the monumental Tierschicksale (Figure 14). Here, instead of a calm scene of a meditating dog, painted diagonals turn into sharp, crystalline splinters raining as a cosmic storm onto a forest of frightened animals. Our eyes seek and find little of the order from Liegender Hund in the chaos of falling trees and howling deer, boars, and foxes – as German doomsday vision, following, as Frederick Levine makes a case for, Ragnarok from the Eddas.60 Andreas Hüneke discovered in 1994 that the inscription Marc had made on the back of the canvas – »Und alles Sein ist flammend Leid« – was a line of text from the Buddhist Dhammapadam.61

Figure 14. Franz Marc, Tierschicksale (1913). Kunstmuseum Basel. Oil on canvas, 196 by 266 cm.

The artist’s cultural-critical apotheosis of the animal culminates in this hopeless and desperate glorification of sacrifice. The animals become the medium of a struggle that is still spiritual but is at last bloody and fatal, a last-ditch effort to drag Europeans to a higher level of humanity, if not pantheistische unity.

In 1914, after being drafted and sent to the front in France, Marc continued to evoke the language of sleep and dreams in his letters to friends and family, particularly after the death of August Macke in September 1914, a vanishing point of consciousness agonizing in its level of denial. By 1915 Marc lapsed into a hallucinative state, an escape as well as a refusal of the scientific positivism which infused German political and military rhetoric.62 Marc’s friend Paul Klee was the one who tried to put all these aspects of his friend in a puzzling eulogy written shortly after Marc’s death on 4 March 1916.63

Klee found that Marc had taken the animal world as a critical mirror which reflected poorly on the world of humans. The anti-narrative reference to dreams with social content was ultimately relevant only to the animals, encapsulated in the forms of these sleeping-awake creatures.

List of Illustrations

Figure 1. Franz Marc, Liegender Hund im Schnee (1912). Städel Museum, Frankfurt, Germany. Oil on canvas, 62.5 by 105 cm.

Figure 2. Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I (1514). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, USA. Engraving, 24 by 18.5 cm.

Figure 3. Franz Marc, Liegender Russi (1910). Private Collection. Oil on cardboard, 9.5 by 14.5 cm.

Figure 4. Franz Marc, Träumendes Pferd (1913). The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, USA. Watercolor, 40.4 by 46.3 cm.

Figure 5. Franz Marc, (Sibirische Schäferhunde) Sibirische Hunde im Schnee (1909). National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA. Oil on canvas, 60.5 by 60 cm.

Figure 6. Franz Marc, Liegender Hund (Russi) (1909). Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg, Germany. Pencil on paper, Sketchbook XI page 2, inscribed Russi V 09, 12.4 by 19.2 cm.

Figure 7. Théodore Géricault, Le chat blanc (1817). Musée du Louvre, Paris, France. Oil on canvas, 55 by 66 cm.

Figure 8. Franz Marc, Der Tote Spatz (1905). Private collection. Oil on wood panel, 13 by 16.5 cm.

Figure 9. Paul Gauguin, Arearea (Joyeusetés) (1892). Musée d’Orsay, Paris, France. Oil on canvas, 75 by 94 cm.

Figure 10. Paul Gauguin, Mahana No Atua (Le jour de Dieu) (1894). The Art Institute, Chicago, USA. Oil on canvas, 98.3 by 91.5 cm.

Figure 11. Paul Gauguin, L’esprit des morts veille Manaò tupapaú (1892). The Conger Goodyear Collection, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, USA. Oil on cloth, 116.05 by 134.62 cm.

Figure 12. Franz Marc, Liegender Akt in Blumen (1910). Private Collection. Oil on canvas, 72 by 100.5 cm.

Figure 13. Franz Marc, Der Traum (1912). Thyssen-Bornesmisza Museum, Madrid, Spain. Oil on canvas, 100.5 by 135.5 cm.

Figure 14. Franz Marc, Tierschicksale (1913). Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland. Oil on canvas, 196 by 266 cm.

Bibliography

BLEYL, Fritz: »Erinnerungen«. In: Magdalena M. Moeller (ed.): Fritz Bleyl 1880-1966. Berlin 1993.

BRYANT, Gabriele: »Timely Untimeliness. Architectural Modernism and the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk«. In: Mari Hvattum and Christian Hermansen Cordua (eds.): Tracing Modernity. London 2004, p. 156–172.

BÜCHE, Wolfgang: Franz Marc. Die Magie der Schöpfung. Halle 2006.

EDWARDS, Steve and Paul Wood: Art of the Avant-gardes. New Haven / CN 2004.

ESCHENBURG, Barbara: »Das Tier in Franz Marcs Weltanschauung und in seinen Bildern«. In: Annegret Hoberg and Helmut Friedel (eds.): Franz Marc. Die Retrospektive. München 2005, p. 51–71.

FABER, Richard: Franziska zu Reventlow und die Schwabinger Gegenkultur. Köln 1993.

FREUD, Sigmund: Über Träume und Traumdeutung. Ed. by Christoph Türcke. München 2010.

GAUGUIN, Paul: Lettres de Gauguin à sa femme et à ses amis. Ed. by Maurice Malingue. Paris 1949.

GAUGUIN, Paul: Noa Noa. Berlin 1907.

GORDON, Donald E.: »Content by Contradiction«. In: Art in America 70 (1982), p. 76–89.

GUTSCHOW, Kai Konstanty: The Culture of Criticism. Adolf Behne and the Development of Modern Architecture in Germany, 1910-1914. New York / NY 2005.

HICKLECY, Catherine: The Munich Art Hoard. Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy. London 2015.

HOBERG, Annegret and Isabelle Jansen: Franz Marc. Oil Paintings Volume I. The Complete Works. London 2004.

HOBERG, Annegret and Isabelle Jansen: Franz Marc. The Complete Works. Volume III. Sketchbooks and Prints. London 2011.

HOBERG, Annegret: »Franz Marc – Aspekte zu Leben und Werk«. In: Annegret Hoberg and Helmut Friedel (eds.): Franz Marc. Die Retrospektive. München 2005, p. 9–49.

HÜNEKE, Andreas: »Alois Schardt, Franz Marc und Halle«. In: Wolfgang Büche (ed.): Franz Marc. Die Magie der Schöpfung. Halle 2006, p. 27–48.

HÜNEKE, Andreas: Franz Marc, Tierschicksale. Kunst als Heilsgeschichte. Frankfurt / M. 1994.

JÄHNER, Horst: Franz Marc. Dresden 1972.

JANSEN, Isabelle: »The Yearning for an Unspoilt World. Exotic Motifs in the Art of Franz Marc«. In: Annegret Hoberg and Helmut Friedel (eds.): Franz Marc. The Retrospective. München 2005.

KANDINSKY, Wassily and Franz Marc: Im Kampf um die Kunst. Antwort auf den »Protest deutscher Künstler« mit Beitr. deutscher Künstler, Galerieleiter, Sammler und Schriftsteller. München 1911.

KANDINSKY, Wassily: Über das Geistige in der Kunst. München 1912.

KANDINSKY, Wassily and Franz Marc: Der Blaue Reiter Almanach. München 1912.

KANDINSKY, Wassily and Franz Marc: The Blaue Reiter Almanach (1912). Documentary edition. Ed. by Klaus Lankheit. London 1974.

KLEE, Paul: Tagebücher 1898-1918. Ed. by Wolfgang Kersten. Stuttgart 1988.

KLINGENDER, Francis D.: Animals in Art and Thought to the End of the Middle Ages. Cambridge / MA 1971.

KOST, Otto-Hubert: Von der Möglichkeit. Das Phänomen der selbstschöpferischen Möglichkeit in seinen kosmogonischen, mythisch-personifizierten und denkerisch-künstlerischen Realisierungen als divergenztheologisches Problem. Göttingen 1978.

KROPMANNS, Peter: »Gauguin in Deutschland. Rezeption mit Mut und Weitsicht«. In: Georg W. Költzsch (ed.): Paul Gauguin. Das verlorene Paradies. Köln 1998.

KUZNIAR, Alice A.: Melancholia’s Dog. Chicago 2006.

LANGNER, Johannes: »Symbole auf die Altäre der kommenden geistigen Religion. Zur Sakralisierung des Tierbildes bei Franz Marc«. In: Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen in Baden-Württemberg. Berlin 1981.

LANGNER, Johannes: »Iphigenie als Hund. Figurenbild im Tierbild bei Franz Marc«. In: Rosel Gollek (ed.): Franz Marc 1880-1916. München 1980.

LANKHEIT, Klaus: »Der Blaue Reiter – Präzisierungen«. In: Der Blaue Reiter Exhibition Catalogue. Bern 1986.

LANKHEIT, Klaus: Franz Marc. Katalog der Werke. Köln 1980.

LANKHEIT, Klaus: Franz Marc. Sein Leben und seine Kunst. Köln 1976.

LANKHEIT, Klaus: Franz Marc. Berlin 1950.

LAVEISSIÉRE, Sylvain. »Le chat mort. Un Géricault inédit«. In: Revue du Louvre 53 (2003), p. 5–22.

LENMAN, Robin: Artists and Society in Germany, 1850-1914. Manchester 1997.

LEVINE, Frederick S.: The Apocalyptic Vision. The Art of Franz Marc as German Expressionism. New York 1979.

LIPPS, Theodor: Ästhetik. Psychologie des Schönen und der Kunst. Hamburg 1903.

LOERS, Veit: »Zwischen den Spalten der Welt – Franz Marcs okkultes Weltbild«. In: Bernd Apke and Ingrid Ehrhardt (eds.): Okkultismus und Avantgarde. Von Munch bis Mondrian 1900-1915. Ostfildern 1995.

MACKE, August and Franz Marc: Briefwechsel. Ed. by Wolfgang Macke. Köln 1964.

MAKELA, Maria Martha: The Munich Secession. Art and Artists in Turn-of-the-Century Munich. Princeton / NJ 1990.

MARC, Franz: »Die konstruktiven Ideen der neuen Malerei«. In: PAN 2.18 (1912), p. 527–531.

MARC, Franz: »Die ›Wilden‹ Deutschlands«. In: Klaus Lankheit (ed.): Blaue Reiter Almanach. London 1974, p. 5–7.

MARC, Franz: Schriften. Ed. by Klaus Lankheit. Köln 1978.

MARC, Franz: »Der Blaue Reiter Almanach (Advertising Brochure)«. In: Klaus Lankheit (ed.): Der Blaue Reiter. Dokumentarische Neuausgabe. München 1987.

MARC, Franz: Briefe, Schriften, Aufzeichnungen. Ed. by Günter Meißner. Leipzig 1989.

MARC, Franz: Écrits et correspondances. Ed. by Maria Stavrinaki. Paris 2006.

MARC, Franz: Postkarte an Herwarth Walden. Der Sturm (Nachlass), Deutsches Archiv für Bildende Kunst im Germanischen Nationalmuseum, Nürnberg.

MÄRZ, Roland: Franz Marc. Berlin 1987.

MASER, Cornelia: Von der Weltanschauung zur Weltdurchschauung – Franz Marc und die Abstraktion. Berlin 2010.

PALMER, Norman: »Unclaimed Art and the Duty of Active Pursuit. Cornelius Gurlitt and the Hidden hoard«. In: Art Antiquity & Law 19 (2014), p. 41–57.

PARET, Peter: German Encounters with Modernism. 1840-1945. New York 2001.

PARET, Peter: The Berlin Secession. Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany. Cambridge / MA 1980.

PIPER, Reinhard: Das Tier in der Kunst. München 1910.

ROSENHAGEN, Hans: »Die Wilden«. In: Carl Vinnen (ed.): Ein Protest deutscher Künstler. Jena 1911.

ROTERS, Eberhard: »Wassily Kandinsky und die Figur des Blauen Reiters«. In: Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 5. Berlin 1963, p. 201–206.

SCHARDT, Alois J.: Franz Marc. Berlin 1936.

SEDLMAYR, Hans: »Franz Marc oder Die Unschuld der Tiere«. In: Wort und Wahrheit 6 (1951), p. 430–438.

SMITH, David Livingstone: Freud's Philosophy of the Unconscious. Dordrecht 1999.

THOMAS, Kerstin: Welt und Stimmung bei Puvis de Chavannes, Seurat und Gauguin. Frankfurt / M. 2010.

UBL, Ralph: »Entzweiung der Malerei. Géricault um 1820«. In: Einunddreißig. Das Magazin des Instituts für Theorie 14/15 (2010), p. 147–153.

ULRICH, Jessica, Friedrich Weltzien and Heike Fuhlbrügge: »Das Selbst des Tieres und die Identität des Menschen«. In: Jessica Ulrich et al. (eds.): Ich, das Tier. Tier als Persönlichkeiten in der Kulturgeschichte. Berlin 2008.

VINNEN, Carl (ed.): Ein Protest deutscher Künstler. Jena 1911.

VON LÜTTICHAU, Mario-Andreas: »Der Blaue Reiter, in Stationen der Moderne«. In: Die bedeutenden Kunstausstellungen des 20. Jahrhunderts in Deutschland. Berlin 1988, p. 108–129.

WEDEKIND, Gregor: »Der Münchner Blaue Reiter – Bruderschaft der Avantgarde«. In: Richard Faber and Christine Holste (eds.): Kreise – Gruppen – Bünde. Zur Soziologie moderner Intellektuellenassoziationen. Würzburg 2000, p. 109–131.

WEST, Shearer: The Visual Arts in Germany, 1890-1937. Utopia and Despair. New Brunswick / NJ 2001.

WORRINGER, Wilhelm: Abstraktion und Einfühlung. Ein Beitrag zur Stilpsychologie. München 1911.

ZIJLMANS, Kitty and Jos Hoogeveen: Kommunikation über Kunst. Eine Fallstudie zur Entstehungs- und Rezeptionsgeschichte des Blauen Reiters und von Wilhelm Worringers »Abstraktion und Einfühlung«. Leiden 1988.

Eyes Be Closed: Franz Marc's Liegender Hund im Schnee von Jean Marie Carey ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

- 1. Franz Marc: »Die konstruktiven Ideen der neuen Malerei«. In: PAN 2.18 (1912), p. 527–531, here p. 528.

- 2. See for example Albrecht Dürer’s Melencolia I (1514) (Figure 2). In Liegender Hund im Schnee Marc combines Melancholia’s and the dog’s poses.

- 3. Marc provides a thorough and detailed account of the making of this portrait in a letter to August Macke dated 14 February 1911, even going so far as to include a small sketch of the composition and a very detailed description of the mixing and blending of the pigments. Franz Marc and August Macke: Briefwechsel. Ed. by Wolfgang Macke. Köln 1964, p. 44–48.

- 4. Annegret Hoberg and Isabelle Jansen: Franz Marc. Oil Paintings Volume I: The Complete Works, London 2004, p. 152.

- 5. »[…] sogar für etwas gefährlich gefällig.« From the correspondence of Felix Weise and Richard Robert Rive, 1 December 1914. Noted by Andreas Hüneke in »Alois Schardt, Franz Marc und Halle«. In: Wolfgang Büche (ed.): Franz Marc. Die Magie der Schöpfung. Halle 2006, p. 27–48, here p. 27. Liegender Hund im Schnee was part of this exhibition organized in honor of the Sammlung Ludwig and Rosy Fischer’s efforts toward repatriating spoliated art, a comment on the painting’s decades away from the Städel.

- 6. In an auction in 1939 brokered by Hildebrand Gurlitt, Liegender Hund im Schnee was sold to American collector Ray W. Berdeau, who used the services of the Basel office of Paris-based Galerie Beyeler to quietly repatriate the painting to the Städel in 1961. For a full account of the role of the Gurlitt family in brokering the sale, and later, the hoarding of stolen and illegally obtained art, see Norman Palmer: »Unclaimed Art and the Duty of Active Pursuit: Cornelius Gurlitt and the Hidden hoard«. In: Art Antiquity & Law 19 (2014), p. 41–57; as well as Catherine Hickley: The Munich Art Hoard. Hitler’s Dealer and His Secret Legacy. London 2015. Provenance inferred from the data compiled by Hoberg and Jansen: Franz Marc (ref. 4), p. 152.

- 7. I reference the annotated Blaue Reiter Almanach (1912), documentary edition, edited by Klaus Lankheit (London 1974). The citation for the original work is: Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc: Der Blaue Reiter Almanach. München 1912.

- 8. Carl Vinnen (ed.): Ein Protest deutscher Künstler. Jena 1911. For a full account of the various personalities and issues at stake in the Vinnen affair, see Shearer West: The Visual Arts in Germany. 1890-1937. Utopia and Despair. New Brunswick / NJ 2001, p. 185–193; and Robin Lenman: Artists and Society in Germany, 1850-1914. Manchester 1997, p. 60–65.

- 9. For a comprehensive explanation of the market and social forces that faced the historical avant-gardes, two pioneering works by Peter Paret remain peerless: The Berlin Secession. Modernism and Its Enemies in Imperial Germany. Cambridge / MA 1980 and German Encounters with Modernism. 1840-1945. New York 2001. See also: Maria Martha Makela: The Munich Secession. Art and Artists in Turn-of-the-Century Munich. Princeton / NJ 1990.

- 10. Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc: Im Kampf um die Kunst. Antwort auf den »Protest deutscher Künstler« mit Beitr. deutscher Künstler, Galerieleiter, Sammler und Schriftsteller. München 1911, p. 73–75 (Kandinsky) and p. 75–78 (Marc).

- 11. For an analysis of the political and social dynamic of Marc’s position, see Kitty Zijlmans and Jos Hoogeveen: Kommunikation über Kunst. Eine Fallstudie zur Entstehungs- und Rezeptionsgeschichte des Blauen Reiters und von Wilhelm Worringers »Abstraktion und Einfühlung«. Leiden 1988, p. 23–27.

- 12. Marc, Kandinsky, and Gabriele Münter split from the NKVM in rather dramatic fashion. See Macke and Franz Marc: Briefwechsel (ref. 3), p. 65. For more on the NKVM and the circumstances of the fissure, see Klaus Lankheit: »Der Blaue Reiter – Präzisierungen«. In: Der Blaue Reiter Exhibition Catalogue. Bern 1986, p. 223–226 as well as Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau: »Der Blaue Reiter in Stationen der Moderne«. In: Die bedeutenden Kunstausstellungen des 20. Jahrhunderts in Deutschland. Berlin 1988, p. 108–129.

- 13. See Gregor Wedekind: »Der Münchner Blaue Reiter – Bruderschaft der Avantgarde«. In: Richard Faber and Christine Holste (eds.): Kreise – Gruppen – Bünde. Zur Soziologie moderner Intellektuellenassoziationen. Würzburg 2000, p. 109–131; also a first-hand account: Eberhard Roters: »Wassily Kandinsky und die Figur des Blauen Reiters«. In: Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 5 (1963), p. 201–206.

- 14. For an elaboration of the critical abuse heaped upon the Blaue Reiter, see Kai Konstanty Gutschow: The Culture of Criticism. Adolf Behne and the Development of Modern Architecture in Germany, 1910-1914. Columbia University, New York 2005.

- 15. Hans Rosenhagen: »Die Wilden«. In: Carl Vinnen (ed.): Ein Protest deutscher Künstler. Jena 1911, p. 65–69, here p. 68.

- 16. Ibid., p. 67.

- 17. Franz Marc: »Die ›Wilden‹ Deutschlands«. In: Klaus Lankheit (ed.): Blaue Reiter Almanach. London 1974, p. 5–7, here p. 5. Of course Marc was aware of, for example, the retro-utopian ideas of Stefan George, through Kandinsky’s association with the poet and his circle. Sharing enthusiasm for a spiritual art and a belief in the epochal renewal of life through creative pursuits, there were specific thematic and stylistic links between Kandinsky’s works and George’s lyric poetry: particularly imagery of the idyllic garden as a setting for meditation and nostalgia. However, along with Adolf Behne, Kandinsky and George called for collaboration and unification of the arts through opera, theater, music, poetry, and architecture, embracing the relatively recent movement toward Gesamtkunstwerk. On the issue of the tension between the Expressionists’ embrace of progressive social and cultural movements and suspicion of technology and industrial developments, see Gabriele Bryant: »Timely Untimeliness. Architectural Modernism and the Idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk«. In: Mari Hvattum and Christian Hermansen Cordua (eds.): Tracing Modernity. London 2004, p. 156–172. Marc did not seem to share his colleagues’ reservations about technology, writing a favorable 1913 essay on the popularity of photography and the increasing availability of communications such as telephones, the radio, and the telegraph. See »Zur Kritik der Vergangenheit«. In: Franz Marc: Schriften. Ed. by Klaus Lankheit. Köln 1978, p. 118.

- 18. Marc: »Die ›Wilden‹ Deutschlands« (ref. 17), p. 6.

- 19. See Franz Marc: »Zwei Bilder«. In: Klaus Lankheit (ed.): Blaue Reiter Almanach. London 1974, p. 8–12, here p. 12.

- 20. Klaus Lankheit (ed.): Der Blaue Reiter. Dokumentarische Neuausgabe. München 1987, p. 327.

- 21. See Wedekind: »Der Münchner Blaue Reiter« (ref. 13), p. 109–131.

- 22. Marc acknowledges his suicidal ideations and discusses depression openly as well in letters to his brother, Paul Marc, and to August Macke and Maria Marc. See Franz Marc: Briefe, Schriften, Aufzeichnungen. Ed. by Günter Meißner. Leipzig 1989, p. 100–103.

- 23. August Macke was also drawn away from Bonn to Tegernsee, a small town near Sindelsdorf in Oberbayern, where he too worked in the comfortable seclusion of his own studio. Macke writes to Marc in December 1910: »Wie versenkten sich doch früher die Menschen in sich, daher ihre Große Kunst. Heute versenkt man sich in Untergrundbahnen und Caféhäuser. Die Maler aber flüchten in die Einsamkeit und arbeiten an sich selbst. Das ist vielleicht nicht zeitgemäß und modern, aber für Kunst (glaube ich) nützlich.« Macke and Marc: Briefwechsel (ref. 3), p. 27.

- 24. Alice Kuzniar writes on the subject of recueillement and animals in several notable passages from Melancholia’s Dog, among them: »[…] recueillement, or recovery of a collected self, serves in healing melancholia and shame […] Combating the threat of depression, the pet helps […] restore a lost subjectivity and combat a sense of inauthenticity.« Alice A. Kuzniar: Melancholia’s Dog. Chicago 2006, p. 213.

- 25. These monographs are: Alois J. Schardt: Franz Marc. Berlin 1936; Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc. Berlin 1950; and Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc. Sein Leben und seine Kunst. Köln 1976. These are commendable works of scholarship; the authors simply did not have the resources of information about the provenance of missing or hidden works that has emerged in the decades since World War II.

- 26. The confusion, or perhaps in some cases creative assignation, can perhaps be traced back to Weise’s comments about the lack of respectability of animal genre painting, the elevation of which was one of Marc’s goals. Alois J. Schardt, who was also the director of the Moritzburg Museum at Halle from 1926 to 1936, came perilously close to calling the painting Der Gelbe Hund, according to notes from his biography on Marc, despite receiving some cooperation from Maria Marc in its compilation. In any case he finally used the title Der Weiße Hund for the subsequent publication. See Alois J. Schardt: Franz Marc. Berlin 1936, p. 164. A mixed title, Der Weiß-Gelbe Hund, was used by Horst Jähner in the catalogue for a small show of the painter’s work. Horst Jähner: Franz Marc. Dresden 1972, p. 11. A further overview of the naming conventions of the painting in terms of its journey to, from, and back to the Städel is included in: Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc. Katalog der Werke. Köln 1970, p. 180.

- 27. See Annegret Hoberg and Isabelle Jansen: Franz Marc. The Complete Works. Volume III. Sketchbooks and Prints. London 2011. Images bearing the name Liegender Russi are found at least in sketchbooks V, VIII, IX, and XI. Not all of Marc’s sketchbooks have been accounted for, with many missing pages and no agreement on how the now-unbound leaves were originally organized. However, the available data indicates Marc was committed to the idea of identifying Russi by name, and that he devoted much practice to making copies of the dog in the physical and psychological state of daydreaming, or somnambulance.

- 28. See again the catalogues raisonnés compiled by Jansen and Hoberg for many examples. Generally speaking a very high number of Marc’s human and non-human animal subjects are shown in states of calm reverie, which argues for his determination to convey a complex sense of the interiority of his painted subjects while allowing us to some extent to imagine and identify with their psychological states.

- 29. In Marc’s lengthy letter to August Macke about making the painting, Marc describes checking out some library books about color theory only to discard their instruction for an uncertain, experimental approach. Macke and Marc: Briefwechsel (ref. 3), p. 44–48: »Meine paar abergläubischen Begriffe über Farben dienen mir jedenfalls besser als alle diese Theorien. […] Wenn Du aber denkst, dass ich mir ganz klar über seine Anwendung bin, dann täuschst Du Dich leider«.

- 30. Franz Marc’s unedited letter to Reinhard Piper appears in: Marc: Briefe, Schriften und Aufzeichnungen (ref. 22), p. 30–31.

- 31. When Marc’s brother Paul suggested to the artist that he pursue one of the new psychoanalytic therapies to treat his depression, Franz, in a disparaging reference to Freud, tells Paul: »Du bist derjenige, mit dem Bart.« Franz Marc to Paul Marc: Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Archiv für bildende Kunst: Franz Marc Nachlass, (11 June 1906). Freudian and Jungian psychoanalysis was firmly established to the point of being a trope, particularly amid the residents of München’s bohemian quarter, Schwabing, where Marc resided. See Richard Faber: Franziska zu Reventlow und die Schwabinger Gegenkultur. Köln 1993. Psychiatry figures prominently in the journals and stories of zu Reventlow, with Marc himself appearing thinly veiled in one of her romans à clef.

- 32. The case of Félida X. is recounted in: Sigmund Freud: Über Träume und Traumdeutung. Ed. by Christoph Türcke. München 2010, p. 150–168. The overlap in Freud’s linguistic use of dreaming and somnambulism regarding Félida X. is noted in: David Livingstone Smith: Freud’s Philosophy of the Unconscious. Dordrecht 1999, p. 53–54.

- 33. Jessica Ulrich, Friedrich Weltzien and Heike Fuhlbrügge (eds.): »Das Selbst des Tieres und die Identität des Menschen«. In: Jessica Ulrich et al.(eds.): Ich, das Tier. Tier als Persönlichkeiten in der Kulturgeschichte. Berlin 2008, p. 9–13, here p. 10.

- 34. Roland März gives an attentive formal analysis of the painting but characterizes Russi as being asleep in: Roland März: Franz Marc. Berlin 1987, p. 9. One author does make note of the contradictorily alert state of apparently sleeping creatures in another of Marc’s images of restful animals, Die Weiße Katze (Kater auf gelbem Kissen) (1912), pointing out the that the cats’ ears are pricked and forward-facing. See Wolfgang Büche: Franz Marc. Die Magie der Schöpfung. Halle 2006, p. 9–19, here p. 13.

- 35. Franz Marc: Écrits et correspondances. Ed. by Maria Stavrinaki. Paris 2006, p. 68–71. Marc, who was bilingual in French and German, kept a diary of his trip to Paris in 1904 in French, and notes almost daily excursions to the Louvre.

- 36. Regarding Géricault’s cat and other animal paintings, see Sylvain Laveissiére: »Le chat mort. Un Géricault inédit«. In: Revue du Louvre 53 (2003), p. 22; and Ralph Ubl: »Entzweiung der Malerei. Géricault um 1820«. In: Einunddreißig. Das Magazin des Instituts für Theorie 14 / 15 (2010), p. 147–153, here p. 147. On pet portraits from the tradition of academic art to more discursive practices, particularly within a political framework but also more generally see Francis D. Klingender: Animals in Art and Thought to the End of the Middle Ages. Cambridge / MA 1971.

- 37. Marc’s often quoted rules governing color theory were in fact a running joke between himself and Macke and not meant at all as seriously as they have been taken by earlier scholars: »Ich werde Dir nun meine Theorie von Blau, Gelb und Rot auseinandersetzen, die Dir wahrscheinlich ebenso ›spanisch‹ vorkommt wie mein Gesicht. […] Schreib mir bitte, ob Du diese Anschauungen frevelhaft und unhaltbar findest oder ob Du ähnliche Erfahrungen gemacht hast.« Macke and Marc: Briefwechsel (ref. 3), p. 27–30.

- 38. Regarding the perception of critics of Marc’s elevation of the animal image to the level of classical human figurative painting, see Johannes Langner: »Iphigenie als Hund. Figurenbild im Tierbild bei Franz Marc«. In: Rosel Gollek (ed.): Franz Marc 1880-1916. München 1980, p. 50–73, here p. 69; also see Johannes Langner: »Symbole auf die Altäre der kommenden geistigen Religion. Zur Sakralisierung des Tierbildes bei Franz Marc«. In: Jahrbuch der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen in Baden-Württemberg. Berlin 1981, p. 79–98; and Barbara Eschenburg: »Das Tier in Franz Marcs Weltanschauung und in seinen Bildern«. In: Annegret Hoberg and Helmut Friedel (eds.): Franz Marc. Die Retrospektive. München 2005, p. 51–71.

- 39. See Annegret Hoberg: »Franz Marc – Aspekte zu Leben und Werk«. In: Hoberg and Friedel: Franz Marc. (ref. 38), p. 9–49, here p. 37.

- 40. Cited by Reinhard Piper as part of a conversation with Marc in: Reinhard Piper: Das Tier in der Kunst. München 1910, p. 190.

- 41. Veit Loers: »Zwischen den Spalten der Welt – Franz Marcs okkultes Weltbild«. In: Bernd Apke and Ingrid Ehrhardt (eds.): Okkultismus und Avantgarde. Von Munch bis Mondrian 1900-1915. Ostfildern 1995, p. 266–269, here p. 266.

- 42. Marc: Schriften (ref. 17), p. 99–100. In this passage the square brackets are by Marc, who used them in his unpublished notations.

- 43. I am interpreting this as an extension of Marc’s invented term Animalisierung as Beseeltheit, meaning the condition of being endowed with Seele. For an ontological investigation of the term itself noninclusive of Marc’s art see Otto-Hubert Kost: Von der Möglichkeit. Das Phänomen der selbstschöpferischen Möglichkeit in seinen kosmogonischen, mythisch-personifizierten und denkerisch-künstlerischen Realisierungen als divergenztheologisches Problem. Göttingen 1978, p. 265–267.

- 44. Eschenburg: »Das Tier in Franz Marcs Weltanschauung und in seinen Bildern« (ref. 38), p. 51–71. Eschenburg claims Marc was greatly influenced by Wilhelm Bölsche. Though trained as an archaeologist and philosopher, Bölsche was a naturalist after Marc’s own heart in that Bölsche observed and recorded data about animals and plants and reported on them in a series of self-published guides. In 1915 Marc expressed an interest in several of Bölsche’s newer nature fact-books in letters to Maria Marc: »Wenn Du je in Leseüberdruß kommst (d.h. wenn man keinen Shakespeare, Hoffmann, Dostojewsky oder Hölderlin lesen will), – so lies Fabre, Bölsche und dergleichen. Ich kann mir gar nichts Anregenderes und Befriedigenderes als Zeitvertreib und Bildung denken, als das Forschen dieser Naturwissenschaftler: Entstehung und Ahnenfolge der Pflanzen und Tierwelt, die geologischen Zeitalter (letzteres ganz besonders), Insektenleben, Sternenlehre u.s.w. Kennt eigentlich [Heinrich] Kam[insky] viel in diesen Dingen.« From: Marc: Briefe, Schriften, Aufzeichnungen (ref. 22), p. 179–180. (My brackets identify the composer Heinrich Kaminsky, a friend of the Marcs.)

- 45. In 1890, the retinal image of a beetle’s eye had been successfully transferred to a photographic plate – this is what Marc seems to be referring to in the letter quoted above. See again Loers: »Zwischen den Spalten der Welt« (ref. 41), p. 269.

- 46. Marc: Briefe, Schriften, Aufzeichnungen (ref. 22), p. 25–27. The painters were only new to Marc, since Van Gogh died in 1890 and Gauguin in 1903.

- 47. See Isabelle Jansen: »The Yearning for an Unspoilt World: Exotic Motifs in the Art of Franz Marc«. In: Hoberg and Friedel: Franz Marc. (ref. 38), p. 73–89. In the chapter »The Yearning for an Unspoilt World: Exotic Motifs in the Art of Franz Marc« Isabelle Jansen gives an extensive account of Marc’s visits to Paris in terms of his exposure there to art from Japan, Cameroon, India, and China. Jansen does a far more comprehensive analysis of Marc’s Liegender Akt in Blumen (1910) to Paul Gauguin’s L’esprit des morts veille Manaò tupapaú (1892) than the one given here. The English translation of the retrospective contains a different version of this essay than the one in the original German catalogue. The English version is the one referenced here.

- 48. Paul Gauguin: Noa Noa. Berlin 1907.

- 49. For a discussion of this terminology as it relates to both Marc’s interest in Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche and nonobjective painting, see Cornelia Maser: Von der Weltanschauung zur Weltdurchschauung – Franz Marc und die Abstraktion. München 2010, p. 1–56. I do not believe Marc ever made or intended to think of what Maser calls Abstraktion in the sense of gegenstandslose Kunst, but her definition of the terms in Marc’s canon is helpful.

- 50. On the positive and unfavorable connotations of the concept of the decorative in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, see Steve Edwards and Paul Wood: Art of the Avant-Gardes. New Haven / CN 2004, p. 91.

- 51. For a thorough visual analysis of Gauguin’s Manaò Tupapaú (L’esprit des morts veille), see Donald E. Gordon: »Content by Contradiction«. In: Art in America 70 (1982), p. 76–89, here p. 78.

- 52. See also Peter Kropmanns: »Gauguin in Deutschland. Rezeption mit Mut und Weitsicht«. In: Georg W. Költzsch (ed.): Paul Gauguin. Das verlorene Paradies. Köln 1998, p. 252–271.

- 53. See Fritz Bleyl: »Erinnerungen«. In: Magdalena M. Moeller (ed.): Fritz Bleyl 1880-1966. Berlin 1993, p. 214. Moeller cites the Brücke Archiv in Berlin as the source for this information.

- 54. See again Jansen: »The Yearning for an Unspoilt World« (ref. 47), p. 88. In thoughtful observation made during his years of self-imposed exile after World War II, Hans Sedlmayr, the Austrian art historian, relocated to Bayern, remarked that Marc’s animals shown resting in nature signaled both unspoiled nature and the presence of strange forces for Marc, noting: »[…] etwas Ähnliches wie für Gauguin die Menschen der Südsee […] eine Spur des verlorenen Paradieses der Unschuld und damit der Schönheit.« Hans Sedlmayr: »Franz Marc oder Die Unschuld der Tiere«. In: Wort und Wahrheit 6 (1951), p. 430–438.

- 55. See Kerstin Thomas: Welt und Stimmung bei Puvis de Chavannes, Seurat und Gauguin. Frankfurt / M. 2010, p. 167.

- 56. Letter from Paul Gauguin to André Fontainas, March 1899. Paul Gauguin: Lettres de Gauguin à sa femme et à ses amis. Ed. by Maurice Malingue. Paris 1949, p. 286–290, here p. 288: »Ici, prés de ma case, en plein silence, je reve á des harmonies violentes […]. Figures animals d’une rigidité statuaire: je ne sais quoi d’ancien, d’auguste, religieux dans le rhythme de leur geste, dans leur immobilité rare. Dans des yeux qui revent, la surface trouble d’une énigme insondable. Et voilà la nuit – tout repose. Mes yeux se ferment pour voir sans comprendre le reve dans l’espace infini qui fruit devant [moi].«

- 57. See Franz Marc: »Die 100 Aphorismen. Das zweite Gesicht«. In: Marc: Schriften (ref. 17), p. 195.

- 58. See Franz Marc to Annette von Eckardt, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Archiv für bildende Kunst: Franz Marc Nachlass (11 July 1908).

- 59. Letter from Franz Marc to Maria Marc, 28 March 1915. Marc: Briefe, Schriften, Aufzeichnungen (ref. 22), p. 133.

- 60. See Frederick S. Levine: The Apocalyptic Vision. The Art of Franz Marc as German Expressionism. New York 1979.

- 61. Hüneke’s discovery, was made many years subsequent to Levine’s book, which is essentially a long essay based upon the very interesting premise that Marc’s Tierschicksale can be interpreted as an image of Ragnarok from Norse mythology. Unfortunately this later development has cast a pall over Levine’s research; however, his creative interpretation is still very interesting. Andreas Hüneke: Franz Marc, Tierschicksale. Kunst als Heilsgeschichte. Frankfurt / M. 1994, p. 15.